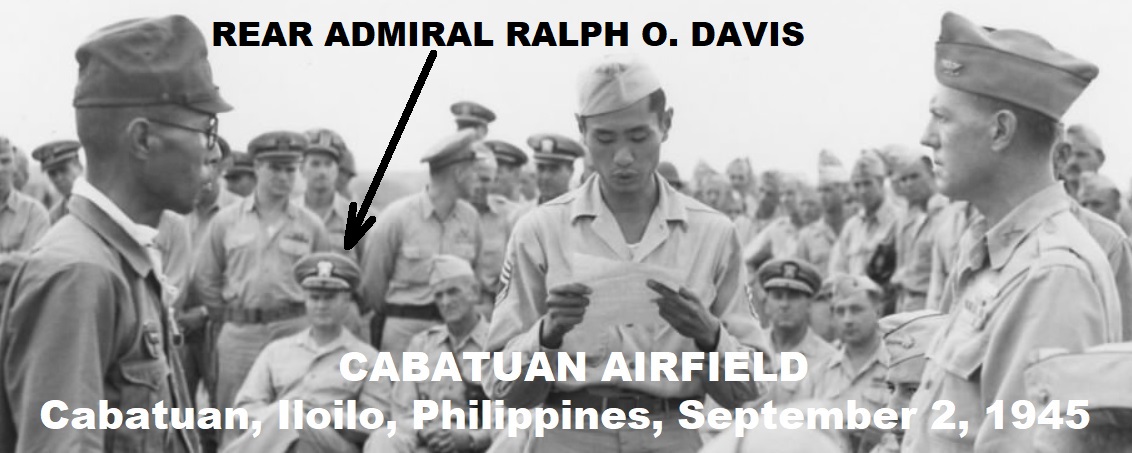

JAPANESE SURRENDER SIGNING CEREMONY AT CABATUAN AIRFIELD ON SEPTEMBER 2, 1945

Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines

by RONNIE MIRAVITE CASALMIR (California U.S.A.), cabatuan @ gmail.com

August 10, 2015 (later edited for additional details)

2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. Events like the signing of the surrender instrument aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945 are being commemorated to remind us of the end of years of suffering and horror on all sides.

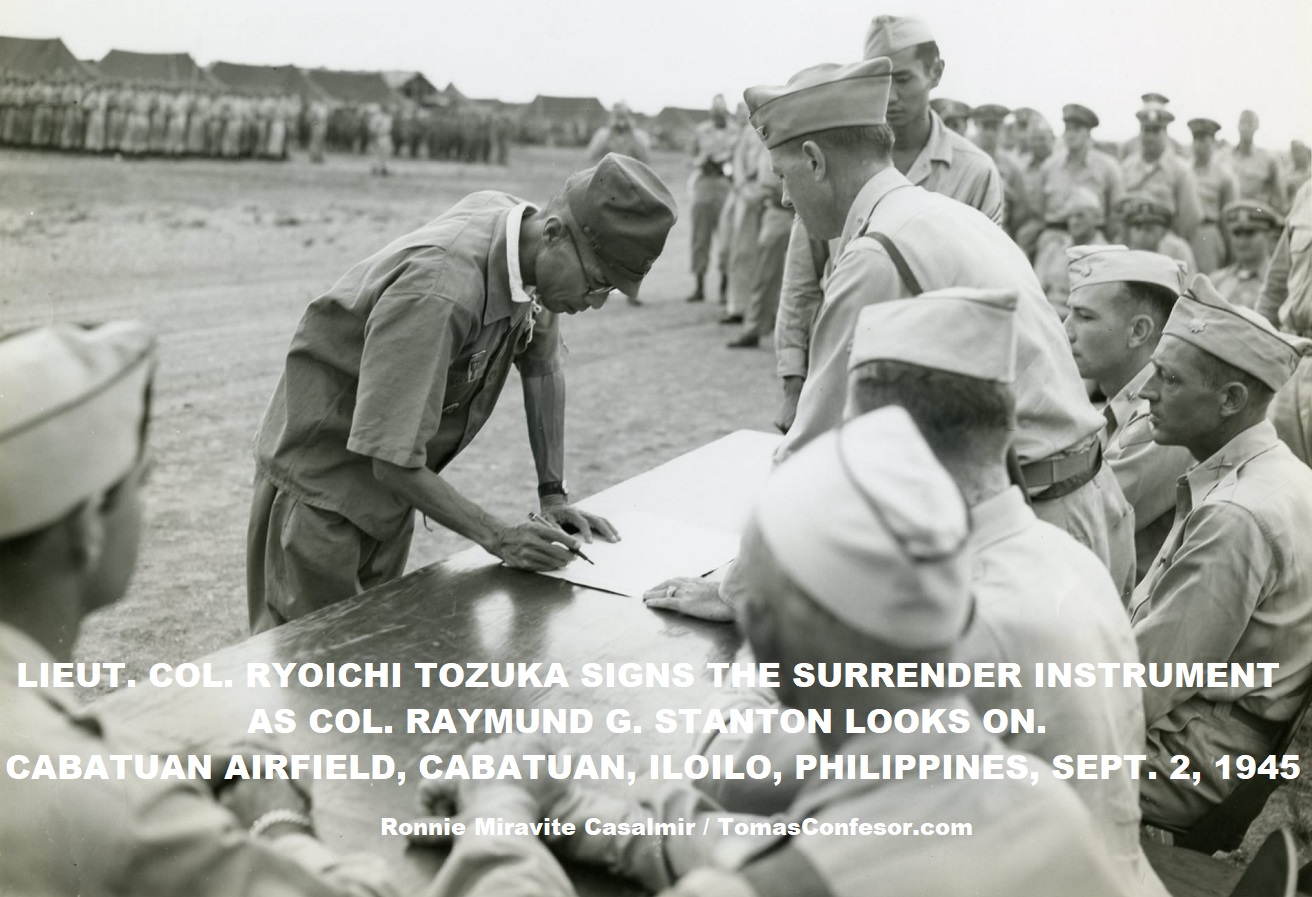

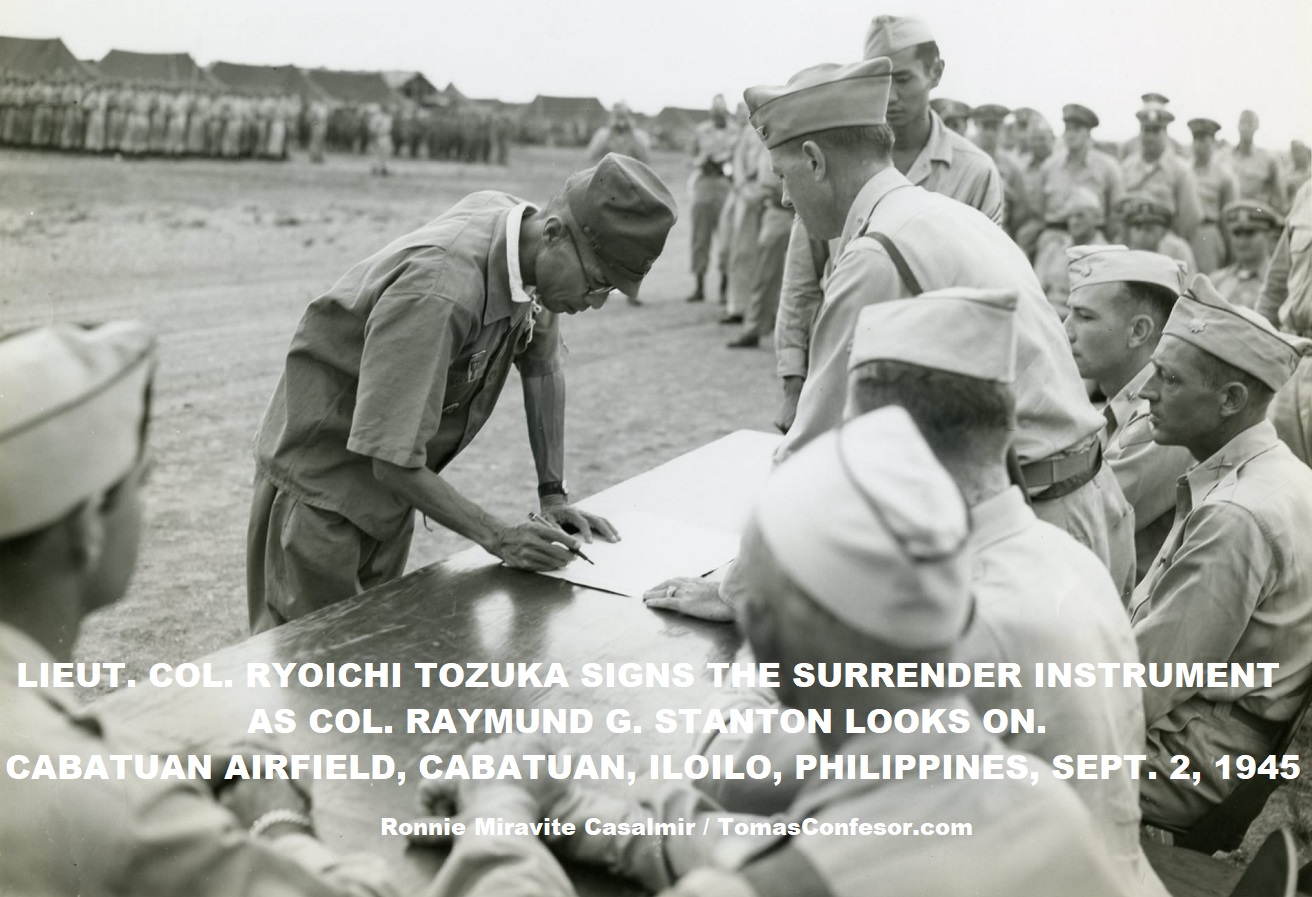

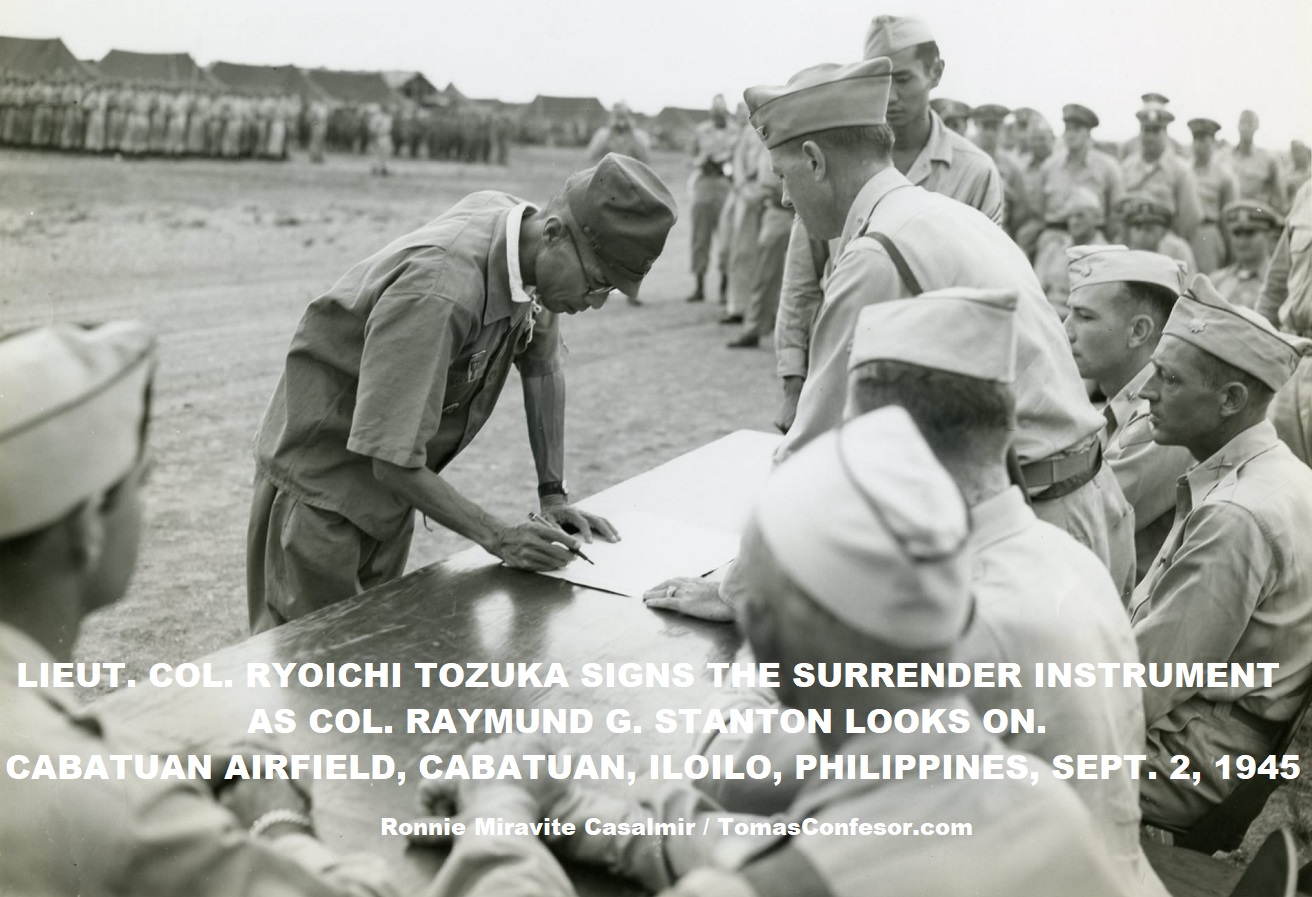

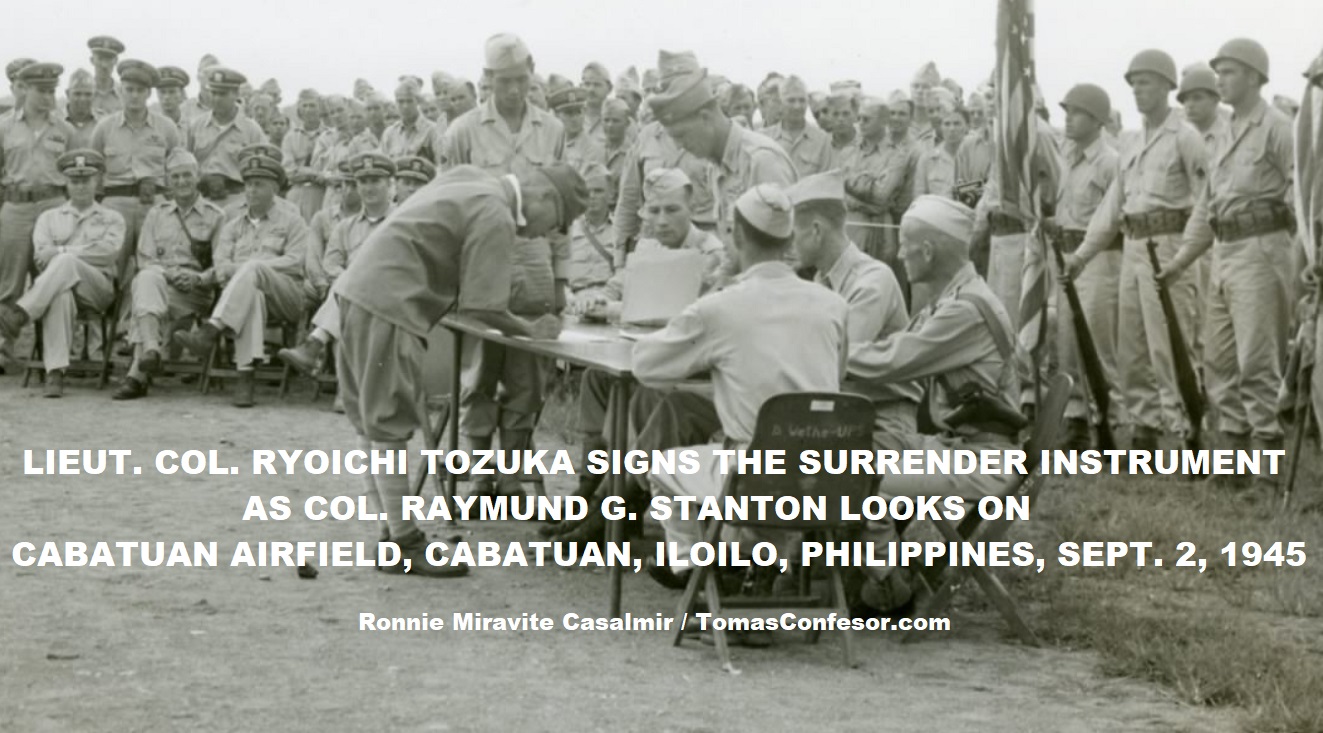

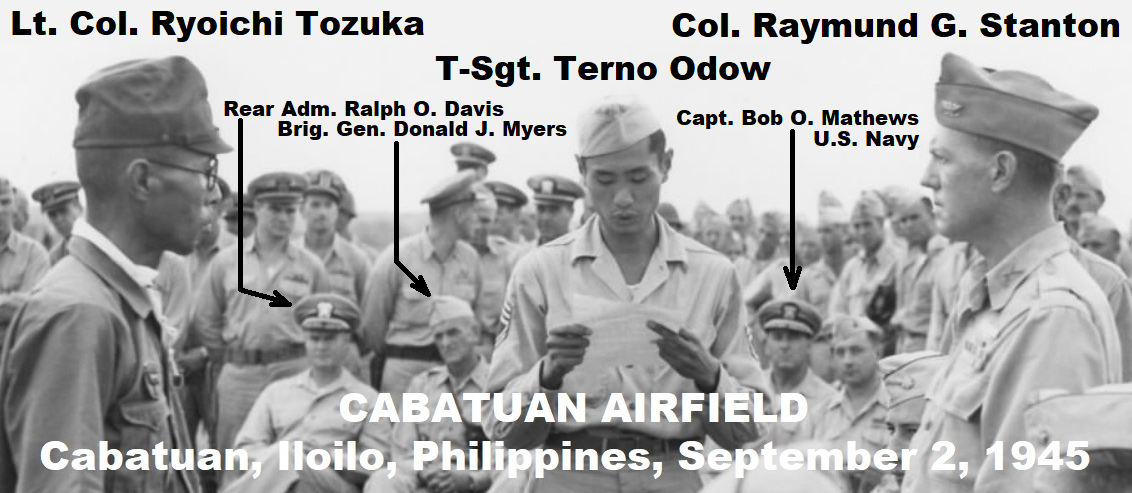

In Panay Island, the end of World War II came with the signing by Lt. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka of the surrender instrument in Cabatuan Airfield, the same day as in Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945.

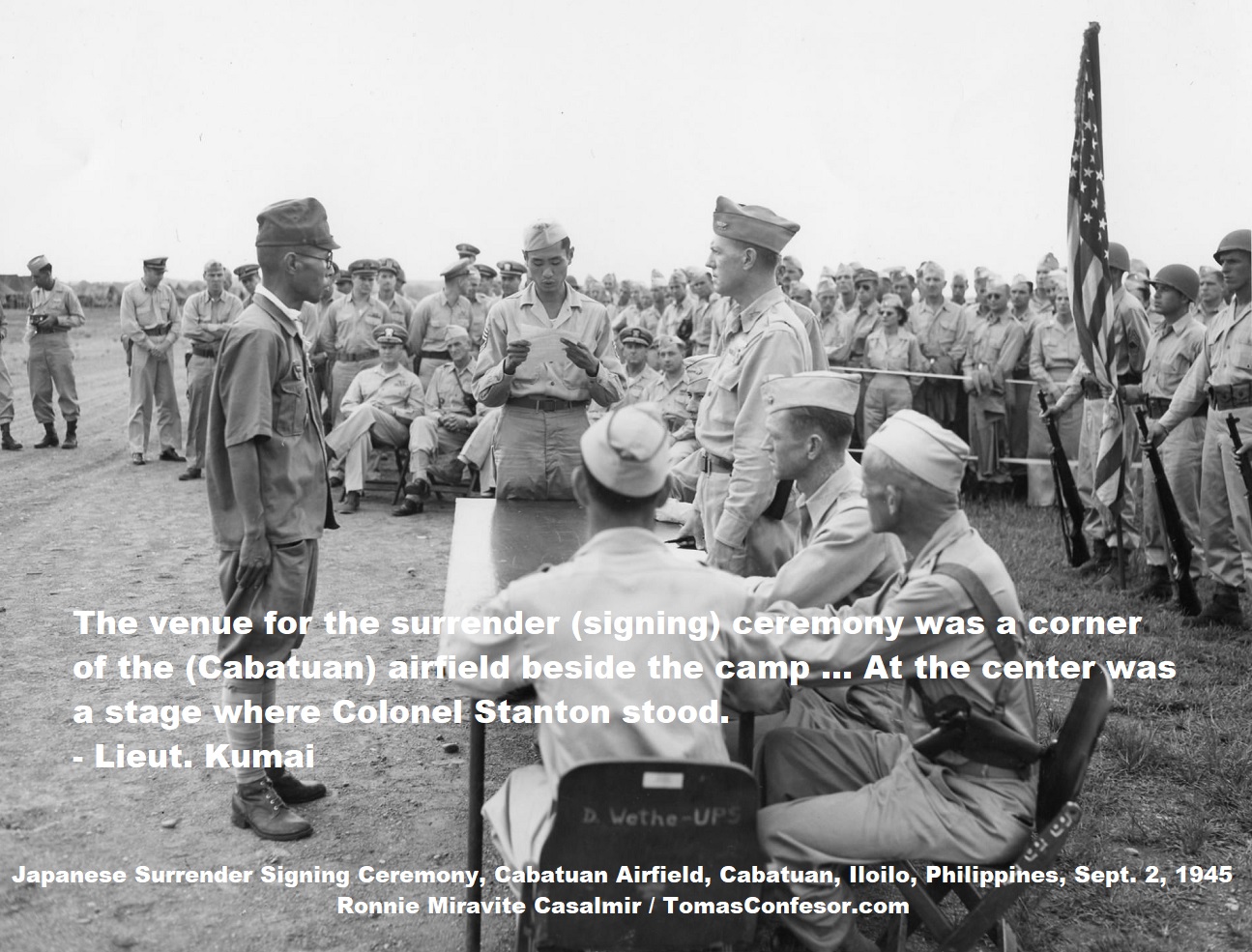

Protocol dictates that the surrender of a Colonel be received by another Colonel, and so, Col. Raymund G. Stanton, the commanding officer of the 160th Infantry Regiment, was designated to receive, even though his superiors were also present.

In attendance to witness the ceremony were Brigadier General Donald J. Myers, commanding the 40th Infantry Division, and Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis, USN, commanding the 13th Amphibious Group.

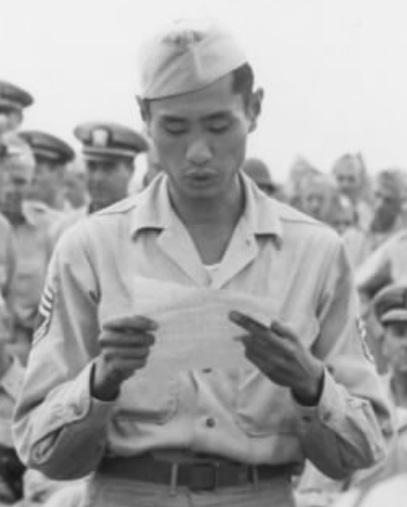

T-Sgt. Terno Odow of the 180th Language Detachment served as translator.

Around noontime, all the Japanese officers were assembled by Lt. Col. Tozuka.

They marched to the "stage" at a corner of Cabatuan Airfield where Col. Stanton was.

The surrender instrument was read by the Japanese-American translator T-Sgt. Terno Odow.

Afterwards, Lt. Col. Tozuka signed the surrender instrument as Col. Stanton looked on.

Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signs the surrender instrument

as Col. Raymund G. Stanton looks on

Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines, September 2, 1945

Photo by Frank Patrick, from his daughter Gail Rooks

See Barnesville's Frank Patrick photographed Panay Island surrender

CABATUAN AIRFIELD

Lt. Toshimi Kumai

Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines

This airfield was called the Cabatuan Airfield by the Japanese Imperial Army after the Municipality of Cabatuan, Iloilo where it was entirely located.

It was also referred to as Tiring Landing Field by others but this was an inaccurate name as the airfield had installations in adjacent Cabatuan barrios as well, not just in Barrio Tiring, Cabatuan.

Another erroneous name was Santa Barbara Airfield, erroneous because the airfield was not located in the neighboring town. It's important to note that there was never any airfield nor airport in Santa Barbara. All the barrios associated with Cabatuan Airfield were situated in Cabatuan, Iloilo, i.e. Barrio Tiring, Barrio Gaub, Barrio Tabucan.

The current Iloilo Airport, or Cabatuan Airport, which sits on the site of the old Cabatuan Airfield, is also located entirely within Cabatuan, Iloilo.

The Japanese forces operated Cabatuan Airfield during the war, from the time they arrived in Panay in 1942, until they retreated to the mountains in 1945.

Upon their surrender, starting September 1, 1945, the Japanese were brought to Cabatuan Airfield and its POW Camp, and on September 2, 1945, the "formal surrender" or the "surrender signing ceremony" was held.

In his memoir book, Lieut. Toshimi Kumai referred to the airfield several times as Cabatuan Airfield, in addition to describing its location accurately as being in Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines.

Lieut. Kumai's book, "The Blood and Mud in the Philippines," was based on the original publication in Japanese, "Firipin no Chi to Doro: Taiheiyosen Saiaku no Gerirasen" (Tokyo: Jiji Press, 1977). It was translated by Yukako Ibuki, and edited by Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay and Ricardo T. Jose.

Sections of Blood and Mud in the Philippines mentioning Cabatuan Airfield:

Appendix A,

Section 7.3, Section 7.3, Section 7.3, Section 7.4, Section 7.4,

Section 8.1, Section 8.3,

Section 11.2

Sections of Blood and Mud in the Philippines mentioning that Cabatuan Airfield was located in Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines:

Section 1.2, Section 6.2, Section 8.3, Section 10.2

Sections of Blood and Mud in the Philippines mentioning the Cabatuan POW Camp, or Cabatuan Camp:

Appendix A

Section 10.3,

Lieut. Toshimi Kumai

Among the Japanese officers who attended the surrender signing ceremony that day, one stood out from the rest later. His name was Lt. Toshimi Kumai. After the war, and after his incarceration in Japan, he came back to Iloilo to atone for what had transpired during the war. He published his memoir, from which we can glean his accounts of that fateful day.

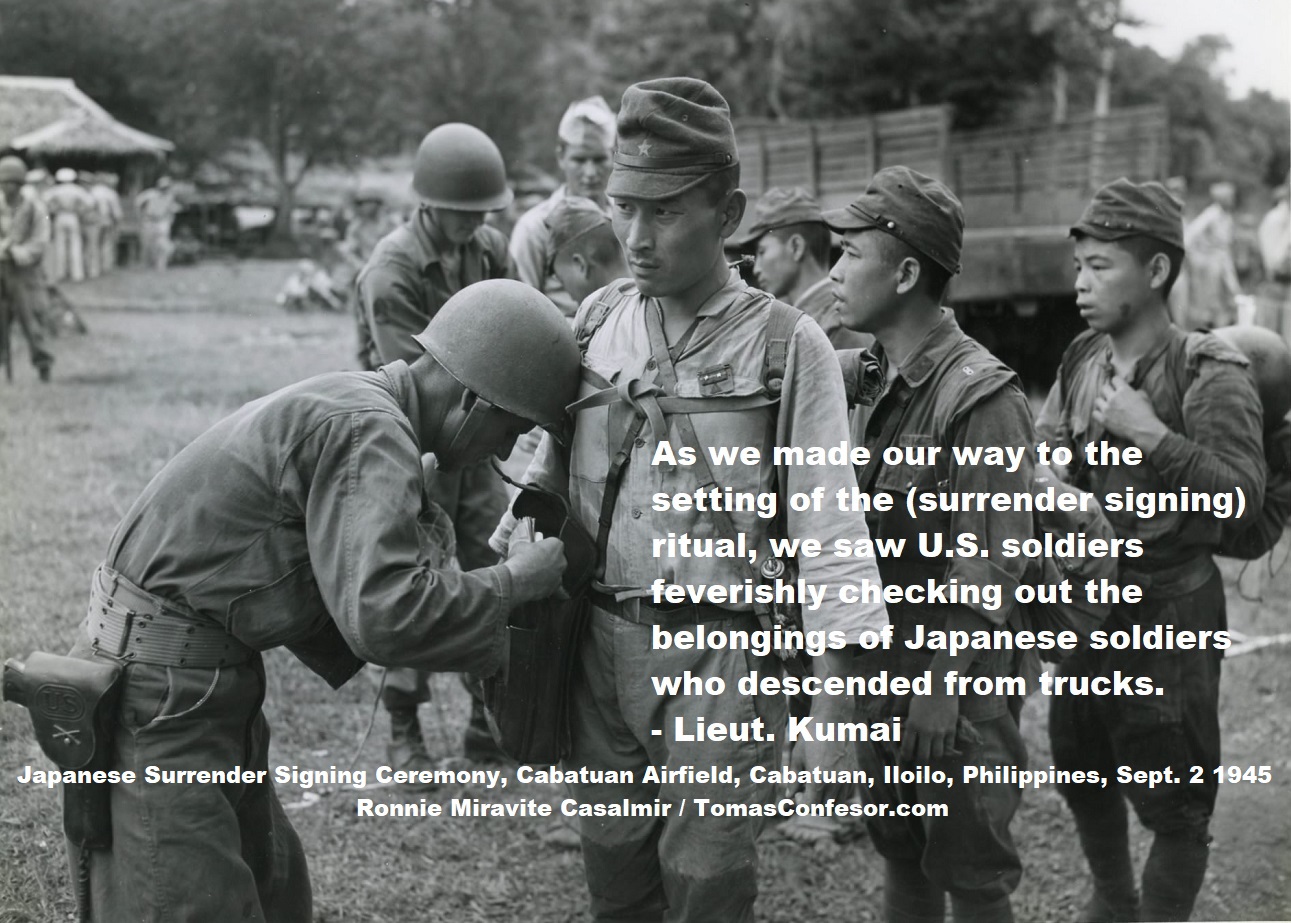

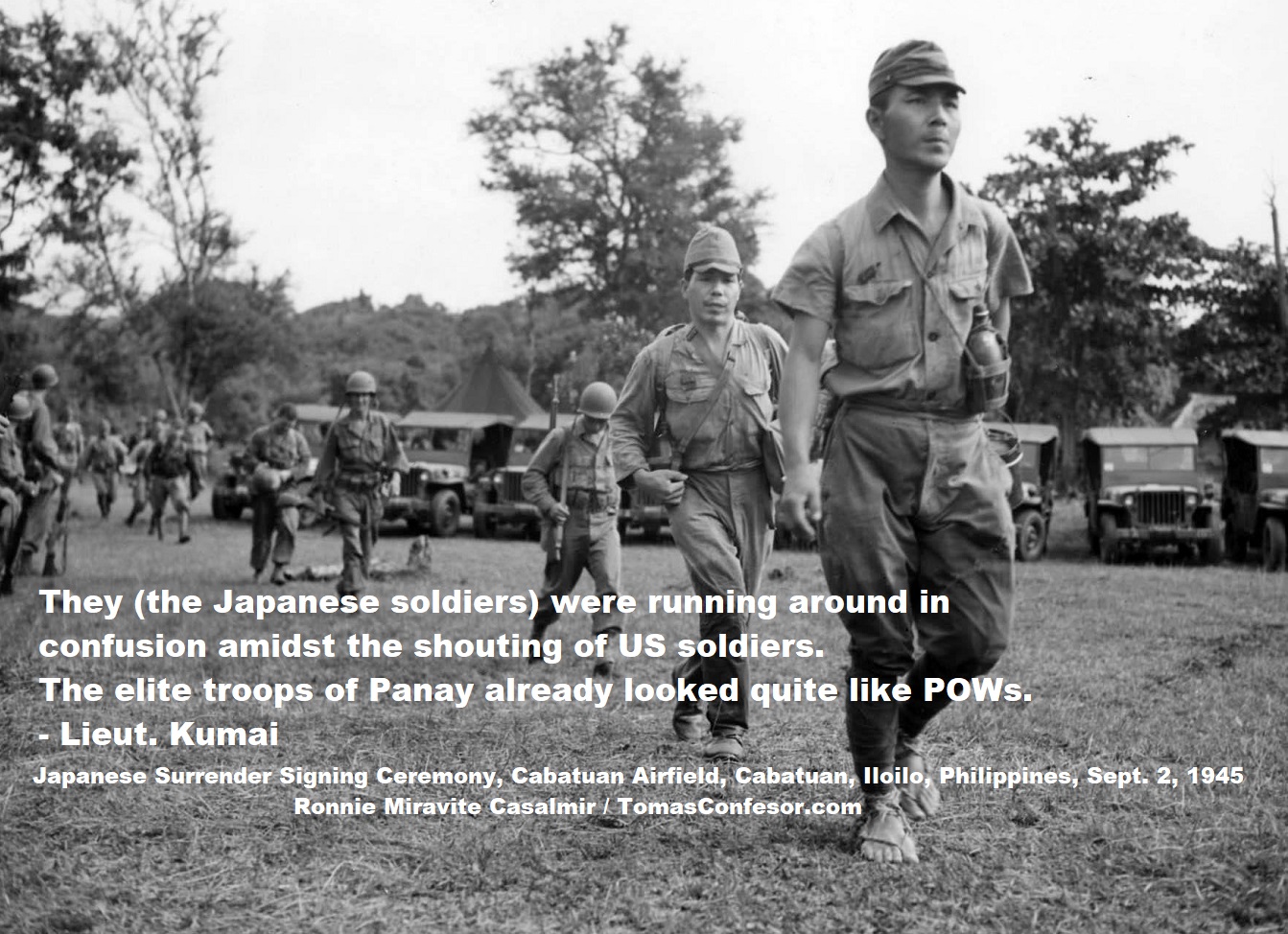

All Japanese Imperial Army officers (at least 16) were assembled to attend the surrender signing ceremony."The next day, a little after noon, all officers were assembled to attend the surrender ceremony. As we made our way to the setting of the ritual, we saw US soldiers feverishly checking out the belongings of Japanese soldiers who descended from trucks. Every one of them had gotten rid of weapons and they were running around in confusion amidst the shouting of US soldiers. The elite troops of Panay already looked quite like POWs."

"The venue for the surrender ceremony was a corner of the airfield beside the camp, where hundreds of military vehicles were parked. A battalion of US troops and a company of intrepid-looking Filipino Army personnel were standing in rows. I carefully observed the behavior of the Filipino soldiers against whom we had fought. In following orders, no movement of theirs looked inferior to that of the American soldiers, making me think of the hard training they must have received."

"At the center was a stage where Colonel Stanton stood. Representing the Japanese Army, the Tozuka unit commander loudly read out the statement of surrender of the Japanese Army to the US Forces. As expected from the look of the setting, the ceremony ended rather simply."

As they made their way to the surrender signing ceremony, they saw US soldiers feverishly checking out the belongings of Japanese soldiers who descended from trucks.

They saw that the Japanese soldiers, every one of them, had gotten rid of weapons and they were running around in confusion amidst the shouting of US soldiers. The elite troops of Panay already looked quite like POWs."

The venue for the surrender signing ceremony was a corner of the airfield beside the camp ... At the center was a stage where Colonel Stanton stood.

Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka

Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka (also spelled Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Totsuka) was the highest ranking Japanese officer in Panay Island when the Americans came in March 1945.

Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri

He commanded the 170th Independent Infantry Battalion, formerly the 37th Independent Infantry Battalion (The 37th or Tozuka Unit was reorganized in December 1943 after the Japanese punitive drive in Panay and became the 170th.)

He withdrew his forces to the mountains, and later came down to surrender in September 1945.

He signed the surrender instrument at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945 as Col. Stanton looked on.

Prior to the signing, he had marched all the Japanese officers to attend the ceremony.

The other Japanese officers and men presumably present at Cabatuan Airfield during the surrender signing ceremony were the following:

Japanese officers under the direct command of Lt. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka

while they were in the mountains in Bocari:

S-1 1st Lt. Toshimi Kumai S-2 1st Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa S-3 1st Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa S-4 1st Lt. Chozo Kyuke Medical 1st Lt. Masataka Egami 1st Co. 1st Lt. Gen Suzuki 2nd Co. 1st Lt. Hajime Fujii 3rd Co. 1st Lt. Masaya Mukohara 4th Co. 1st Lt. Makoto Yoshioka 5th Co. 1st Lt. Yonemoto Ishida 6th Co. 1st Lt. Kunisake Nakamura 7th Co. 1st Lt. Masayoshi Mizutani

Japanese delegation to the surrender negotiations five days before:

Capt. Kaneyuki Koike

1st. Lieut. Toshimi Kumai

1st. Lieut. Sadayoshi Ishikawa

Sergeant Matsuzaki

1st. Lieut. Horimoto

Private First Class UekiCapt. Koike (commanding the Kempei Tai unit on Panay Island), Lt. Kumai and Lt. Ishikawa composed the "advance surrender party" that negotiated the manner of surrender a few days earlier, on August 28, 1945, with Sergeant Matsuzaki as interpreter.

The NCO cadet platoon escorting them from Bocari to Daja Maasin was led by 1st Lieutenant Horimoto, with Private First Class Ueki as interpreter.

The "advance surrender party" met with American representatives at Maasin plaza, and returned back to Bocari afterwards. As agreed upon, the Japanese forces then started to surrender on September 1, 1945, with the formal surrender signing ceremony by Lt. Col. Tozuka happening the following day on September 2, 1945 at Cabatuan Airfield.

Japanese unit in San Jose, Antique:

Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri

1Lt Makoto Yoshioka

2Lt Fukumori Okuda

2Lt Mikio Kai

Sgt Maj Takeji Wada

Sgt Shichiro Inoue

Pfc Akiro Sato

Pfc Heiji Watanabe

Private Second Class Chikaichi Ota

They were from the Japanese unit in San Jose, Antique, which joined up with Lt. Col. Tozuka in Bocari, Leon when the Japanese retreated to the mountains. They were later put on trial for the killing of American prisoners in March 1945 in San Jose.

2Lt Noriyuki Ôtsuka

Master Sergeant Tadataka Kuwano

Later tried for the killing of American civilians in December 1943 in Tapaz.

Sergeant Tokizo Makita

Corporal Hisaki Itai

Also later accused of the murder of civilians during the period of their service at the garrison in Leon, Iloilo, according to Lieut. Kumai.

Tsukasa Shimojo

Michio Ikeda

Yoriichi Natsu

Fujinosuke Moriyama

Sadao Ono

Other Japanese soldiers of the 170th Independent Infantry Battalion who were known to survive the war in Panay.

About 1,200 Japanese soldiers from Bocari, Leon surrendered on September 1-2, 1945. They were brought to Cabatuan Airfield where they were interned at its POW Camp.

Another 500 Japanese soldiers from Mt. Singit, Lambunao surrendered on September 3-4, 1945, and were also brought to and interned at the Cabatuan Airfield POW Camp.

Col. Raymund G. Stanton

Protocol dictates that the surrender of a Colonel be received by another Colonel, and so, Col. Raymund G. Stanton (Col. Raymund Gregory Stanton, sometimes spelled Col. Raymond G. Stanton or Col. Raymond Gregory Stanton) was designated to receive, even though his superiors were also present.

Col. Raymund G. Stanton at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri

Col. Stanton was the commanding officer of the 160th Infantry Regiment.

He captured the serious tone of the surrender in his speech. Standing on the runway of Cabatuan Airfield, he said in part:Today is V-J day ... the day we have been looking forward to for what has seemed an eternity. this day must be set aside to thank almighty God for sparing us the sorrow that lay ahead in the path of war, had hostilities continued.Col. Raymund G. Stanton's words "to thank almighty God for sparing us the sorrow that lay ahead in the path of war, had hostilities continued" were most significant to his unit, the 160th Infantry Regiment, for this regiment would spearhead the invasion of Japan under Operation Olympic had the war continued. They would be the first regiment to invade Japan, and would be transported direct from Iloilo.

The officers and men of the 160th have fought through some of the worst fighting in the south pacific and know only too well what sorrows, hardship and even death itself mean to them. they have been exposed to a cruel and difficult type of warfare for months on end -- going from island to island with only one thought uppermost in mind -- that of crushing the japanese for all time. this goal has now been attained.

The ruthless warlords of japan have been brought to an ignominious end by the will of an indomitable people ..... it is the hope and prayerful wish of every man in this command that the sacrifices, sickness and death of our comrades be remembered by our countrymen in the maintenance of peace to come .....

Blitzkrieg to Cabatuan by the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment

When the 40th Infantry Division arrived in Iloilo on March 18, 1945, it was composed of 4 Infantry battalions. The 185th Infantry Regiment had all of its three battalions present while the 160th Infantry Regiment had only one battalion present, the "2nd Battalion." Its two other battalions would arrive a few days later.

While the three battalions of the 185th Infantry Regiment marched to Iloilo City, the 2nd Battalion of the 160th Infantry Regiment raced to Cabatuan Airfield and the town of Cabatuan in a mechanized blitzkrieg lightning swoop, by way of Cordova, Leon and San Miguel, to liberate Cabatuan Airfield and Cabatuan. They arrived at Cabatuan that very night, at midnight.

Lieut. Kumai had mentioned this long column of vehicles going to Cabatuan while it was passing through Cordova:

Around 200 vehicles such as tanks and military trucks were counted just along the road between Tigbauan and Cordova. Section 8.1Lieut. Kumai added that this is the column that went to Cabatuan Airfield and Cabatuan:

The US tank forces attacked the Cordova position and Cabatuan airfield. Section 8.1Maximo G. Salvador had also observed this long column going to Cabatuan while it was passing through San Miguel:

March 18, 1945. Desiring to see the Americans in flesh, we moved to San Miguel that same morning. Early in the afternoon, hundreds of jeeps and trucks, loaded with GI’s [military slang for American soldiers] passed through the town. The people of San Miguel were so happy that some naughty girls threw their flying kisses at the Americans. The same kisses were returned with boyish smiles.” The foreign presence was, to the townspeople, a glimmer of hope.The 160th Infantry Regiment had mentioned it themselves and provided details:

While the 185th Infantry Regiment dashed madly into the city and were wildly received amidst flowing liquors and fresh eggs, Second Battalion boys (of the 160th Infantry Regiment) made a midnight, mechanized flanking movement into Cabatuan, a small village in the foothills.The 160th Infantry Regiment added:

From there (Cabatuan) our patrols began chasing the Japs in all directions, whenever they were reported by overwrought Filipinos who claimed to be guerrillas.

Cabatuan was a typical, out-of-the-way Filipino village with its nipa huts, city hall and market place all located within a stone's throw of the green-grassed plaza. Overlooking the Plaza was a very large, stone church with high bell tower and green vines crawling over the edifice. In the cold, musty interior hundreds of townspeople hovered in terror of the Japanese who had raided and killed enroute to their retreat. The air of jubilance in the streets gave way to thankfulness and prayer inside.

The morning after our arrival (at Cabatuan), the Plaza, where some of the men had bunked down, was crammed with sight-seeing Filipinos as well as demonstrating guerrillas. The spontaneous parade by the guerrillas was perhaps the weirdest and most gruesome we witnessed. Carrying their long, razor-sharp bolos at their waists, Filipinos carried Japanese heads by the hair. Some had three or four tied to a bamboo pole. Others carried the whole headless, bloated and badly mangled body of a Jap they had killed after torturing. It was an eye-opening sight into the tremendous hatred of the Filipinos for the Japanese.Kumai map showing the movement of the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment from Tigbauan to Cabatuan Airfield and the town of Cabatuan, passing through Cordova, Leon and San Miguel.

Twice during the first morning the soldiers dived for cover and adjusted themselves for a fight, but both alarms were false. In one instance the hysterical cry passed in Visayen and English, "Japanese coming -- Japs coming." The doughboys seeking to get together had to fight their way through thundering crowds of Filipinos running for safety in the church. There was a Jap, but he was a beaten, bloody prisoner of some guerrillas who were bringing him to our headquarters.

MacArthur map showing the same, the movement of the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment from Tigbauan to Cabatuan Airfield and the town of Cabatuan, passing through Cordova, Leon and San Miguel.

Lieut. Col. Lex M. Stout was the commander of the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment. (He's a recipient of the Bronze Star and the Air Medal.)

The 1st Battalion and the 3rd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment arrived in Panay on March 26, 1945.

Col. Stanton had written his wife that he was selected to receive the surrender because of the excellent fighting record of his regiment.

Col. Raymund G. Stanton graduated in 1927 from the United States Military Academy (USMA), also known as West Point.

It appears from the signing photo that Col. Stanton was wearing his West Point class ring while accepting the surrender in Cabatuan.

Another officer who was reportedly involved in accepting the surrender was Lt. Col. James K. Marr, a battalion commander of the 40th Division. (He's a recipient of the Silver Star.)

More on Col. Raymund G. Stanton

Tech. Sgt. Terno Odow

The Japanese-American translator (standing at the end of the table) during the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield was T-Sgt. Terno Odow of the 180th Language Detachment.

T-Sgt Terno Odow at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri.

He had previously drafted four leaflets, in English and Japanese, 40,000 of which were dropped on two Philippine islands (Panay Island and Negros Island). The leaflets were directly responsible for the surrender of 5,000 Japanese troops.

He then drew the assignment of questioning a large portion of about 1,700 Japanese soldiers who surrendered in Panay Island.

Sgt. Odow was an intelligence specialist, interpreter and interrogator.

He speaks fluent Japanese, having spent two years at Keio University, Tokyo, before the outbreak of the war.

He entered service Oct. 21, 1941, and went overseas in November 1942.

He was a veteran of campaigns on Guadalcanal, New Britain, Luzon, Panay and Negros.

He's a recipient of a Bronze Star.

More on Tech. Sgt. Terno Odow

T-Sgt. Terno Odow, seated at the far side of the table,

drew the assignment of questioning a large portion

of about 1,700 Japanese soldiers who surrendered in Panay Island.

Lieut. Herman E. Bulling

The American honor guard standing behind Colonel Raymund G. Stanton came from the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon commanded by Lieutenant Herman E. Bulling.

One member of the honor guard was Pfc. Everett L. Farris. He saw action on Leyte and Mindanao. He wears the Combat Infantry badge, the Asiatic-Pacific ribbon with one campaign star and a Bronze Arrowhead, the Philippine liberation and Good Conduct ribbons.

Other members mentioned were Cpl Harvey H. Miller of Hagerstown Maryland, and Curt Ittner.

In an interview on June 27, 2003, done by Shaun Illingworth and Jared Kosch, with Mrs. Helen Bulling attending, and published by the Rutgers Oral History Archives, Herman E. Bulling states that:

"my I&R Platoon (Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon) was the honor guard for the ceremony and, of course, the Colonel (Col. Raymund G. Stanton) was great on ceremony. I mean, he had long tables set up with the staff officers sitting there, and, in fact, I have, someplace, got pictures of that, too. That was one of the worst impositions I ever made on my father. [I] got those pictures, I sent them home and I said, "Dad, I need forty copies of these," and, at that point, my father, somehow or other, got forty copies made and sent them back to me and every member of my platoon had copies of the surrender ceremonies; Colonel Stanton, accepting the surrender."Herman E. Bulling further adds about the Japanese forces:

"I don't know, he wasn't that much of a big shot, but he was in charge of whoever was up in the hills. They were in terrible shape. They were physically exhausted. They'd probably been in the hills for two or three years (actually 6 months) and they had come down out of the hills only to be put into a stockade, but they were better off there than they had been up in the hills, because the farmers had said that there were raids on their fields, but they couldn't have been getting enough food."

Brig. Gen. Donald J. Myers

Present at the Japanese surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on Sept. 2, 1945 to witness the event was Brig. Gen. Donald J. Myers (Brig. Gen. Donald Johnson Myers, sometimes misspelled as Brig. Gen. Donald J. Meyers or Brig. Gen. Donald Johnson Meyers)

Brig. Gen. Donald J. Myers at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri.

Brig. Gen. Myers was the commanding general of the 40th Infantry Division.

The 160th Infantry Regiment of Col. Raymund G. Stanton was a component of this division.

The Assistant Commander of the 40th Division was Brig. Gen. Robert O. Shoe. He was also present at this surrender signing ceremony.

Brig. Gen. Myers assumed command of the 40th Infantry Division in July 1945. He replaced Maj. Gen. Rapp Brush who commanded the 40th Infantry Division when it landed on Panay in March 1945.

Brig. Gen. Myers remained the commander of the 40th Infantry Division until it was inactivated on April 7, 1946 at Camp Stoneman, California. (It was later reorganized and federally recognized on Oct. 14, 1946 at Los Angeles, California)

Brig. Gen. Donald J. Myers later writes:To the veterans of the 40th Infantry Division - living and dead - whose courage, leadership, and sacrifices attained the unexcelled combat achievements and established the enviable record of the "Sunburst Division" in the Pacific Theater.

Beginning at Guadalcanal and New Britain, this record was continued through the landing at Lingayen Gulf; seizure of the central Luzon plains; participation in the Leyte, Masbate, and Mindanao operations; the lightning liberation of the Islands of Panay and Negros against an enemy superior in numbers; culminated in the occupation of Southern Korea and the liberation of the Koreans from years of Japanese domination.

It was a privilege and a great honor to have been associated with the 40th Infantry Division as one of its leaders.

Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis

Also present at the Japanese surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on Sept. 2, 1945 to witness the event was Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis (Rear Admiral Ralph Otis Davis), commanding the U.S. Navy's 13th Amphibious Group.

Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri

The 13th Amphibious Group was tasked to transport the 40th Division from Iloilo to Korea for occupation.

Rear Admiral Davis and his staff came to Iloilo to supervise this transport operation.

The flagship of the 13th Amphibious Group was the U.S.S. Estes.

The USS Estes arrived in Iloilo on September 1, 1945, from Leyte, with Rear Admiral Davis and his staff on board.

The following day, September 2, 1945, The ship sent a detail ashore to take part in the Japanese surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield.

Norman Lindenberg was a member of that detail and had some documents and pictures taken that day.

John J. DeBenedetto, also on USS Estes, had a similar photo collection. [Norman Lindenberg, John J. DeBenedetto/Thomas DeBenedetto, USS Estes Association]

Departure of the 40th Infantry Division from Panay Island

Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines on September 2, 1945, the same day as the signing on U.S.S. Missouri

Five days later, on September 7, 1945, LSD Carter Hall (Landing Ship Dock Carter Hall) left Panay for Korea, the first ship to do so with the advance party of the 40th Infantry Division and elements of the 532nd EB&SR (532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment).

On the same day, September 7, 1945, the 658th Tractor Battalion assumed control of the Cabatuan Airfield POW Camp.

According to Lieut. Kumai:

In the camp, we were surprised at the delicious food prepared for us but four or five days later, its quality suddenly deteriorated. This was because the 40th Division of the US Army that was in charge of the camp was reassigned for posting in Korea. The night before their departure, 2nd Lieutenant Jones and other officers in charge of the camp came to visit us. It seemed as though they would miss us who had joined in the fighting in Bocari.

More on Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis

Capt. Bob O. Mathews, USN

Capt. Bob O. Mathews (Capt. Bob Orr Mathews), the skipper of USS Estes, which was the flagship of the13th Amphibious Group, was in attendance as well.

Above Left: Capt. Bob O. Mathews at the Japanese surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945.

Above right: photo of Capt. Bob O. Mathews at the U.S.S. Estes Association.

Below: Capt. Bob O. Mathews at the Japanese surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945.

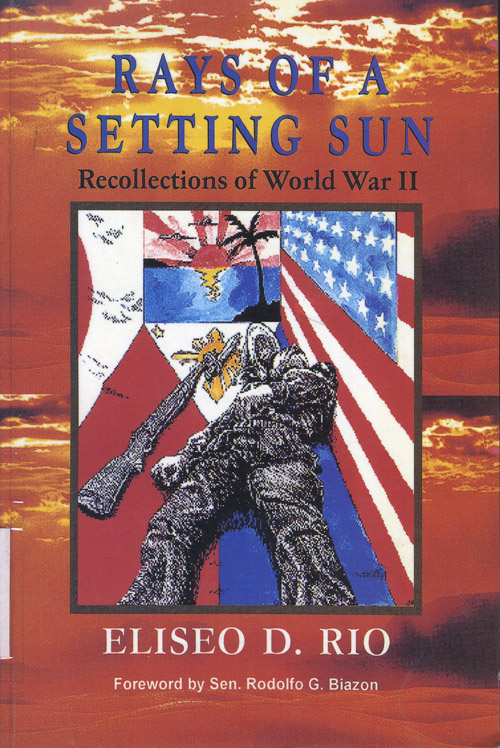

Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

The Filipino infantry company present during the surrender signing ceremony was organized and commanded by Capt. Eliseo D. Rio. Tall men were selected from among the ranks of the 1st Battalion 52nd Infantry Regiment and were given new uniforms and equipment in time for the ceremony.

Capt. Rio describes the event in his book "Rays of the Setting Sun":

Having been called away on official business, the commander of the 52nd Infantry Regiment designated Major Gelveson, 1st Battalion Commander, as his representative in the surrender ceremony and asked him to take charge of all arrangements attendant to it.Lieut. Kumai had this to say about the Filipino company:

In turn, Major Gelveson requested me to organize and command a rifle company, using men from his battalion, which was to act as the honor guard during the ceremony. For the ceremonial company, I picked out the tallest men of the battalion, who were each issued a brand new set of combat uniforms and arms - olive drab combat shirt and pants, canvas combat boots, steel helmet, cartridge belt, bayonet, and m1 rifle. The company officers were similarly dressed but armed instead with .45 caliber pistols.

The venue selected for the surrender ceremony was the grandstand of a sports playground near the runway of Cabatuan Airfield, which was kept operational by the Japanese Air Force during the war.

As early as 0900 Hours of the appointed day, people started to gather in the grandstand as well as around the area in front ringed by a platoon of my special company. The rest of the company was formed with the two platoons in line immediately in the front and center of the stand, facing forward. I and my staff, composed of the Company Executive Officer and the guidon-bearer, took the standard position in front of the formation. A few yards before me was set a rectangular table with two chairs at the side close to me and a lone chair at the other.

By 1030 Hours, the grandstand was filled to overflowing and the people forming a semi-circle on the ground were at least five deep. There was a fairly large group of American servicemen among the crowds at the grandstand, but the majority of the people who came to witness the surrender ceremony consisted of Filipino civilians, a big number of whom were recently demobilized guerrilla.

At about 1100 Hours, the trucks bearing the Japanese arrived. Upon getting down the trucks, the soldiers were formed facing the grandstand about twenty yards in front of the table in a platoon-in-line formation with four squads. The officers formed a single line in front of the platoon, while the commander, alone, positioned himself at the head of his men.

a company of intrepid-looking Filipino Army personnel were standing in rows. I carefully observed the behavior of the Filipino soldiers against whom we had fought. In following orders, no movement of theirs looked inferior to that of the American soldiers, making me think of the hard training they must have received.

Capt. Rio adds:

I was struck by the sight of the enemy remnants. They were all pale and emaciated; literally scarecrows in their dungy and loose-fitting uniform. I was told that when they were served breakfast earlier that morning, they gobbled up their food like a bunch of hungry animals. Undoubtedly, their six months' stay within those severe rain forests of central Panay had wrought alarming deleterious consequences on those Japanese hold-outs. Although in a much lesser scale, the scene was quite reminiscent of what befell the Filipino-American troops in the jungles of Bataan some three and a half years earlier.Lieut. Kumai appears to corroborate:

In the camp, we were surprised at the delicious food prepared for us.

Frank Patrick

Barnesville's Frank Patrick photographed Panay Island surrender

Posted by Walter Geiger in Features

Barnesville The Herald-Gazette, Wednesday, December 7, 2016

On this, the 75th anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Gail Rooks is sharing these photos she found in a medal box belonging to her late father, Frank Patrick. Patrick took the photos during the surrender ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on Panay Island in the Pacific.

The ceremony took place on Sept. 2, 1945, the same day Japan formally surrendered with Gen. Yoshijiro Shigemitsu signing for Japan and Gen. Douglas MacArthur accepting for the Allied Forces on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Patrick had been a projectionist at three local theaters prior to World War II and became a projectionist in the Army along with his duties as a radio operator.

Rooks found the photos and thought it would be appropriate they be shared on the anniversary of the Pearl Harbor atrocity.

Research revealed the story behind the photos which show Col. Ryoichi Tozuka signing the surrender document while Col. Raymond G. Stanton accepts for the U.S. Army. All indications are Frank Patrick, who returned home to run the Barnesville water works for generations, was on the front row. Patrick also become an accomplished framer and wood turner.

The above article and photos were originally posted at

https://barnesville.com/barnesvilles-frank-patrick-photographed-panay-island-surrender/

http://www.barnesville.com/archives/9759-Barnesvilles-Frank-Patrick-photographed-Panay-Island-surrender.html

More on Frank Patrick

Lt. Kenneth Rodriguez

OVERHEARD FROM OVERSEAS

JAP SURRENDER on Panay Island in the Philippines is snapped by Lt. Ken Rodriguez, husband of Mrs. Margaret Rodriguez, Ft. Scott librarian.

Lt. Kenneth Rodriguez with an Infantry Outfit on Panay encloses some photographs along with his news: “I am enclosing some pics of the Japanese surrender here in Panay. Also one of the capitol building at Lingayen, a town on Luzon. I landed right in front of this building on 9 January about 10 minutes after the first wave hit. The Navy punched a few holes in it here and there shortly beforehand. I will never forget that moment or this building.”

Tech. Sgt. Moffet M. Ishikawa

The 180th Language Detachment, which was the language team of the 40th Division, was headed by Richard Child, with Terno Odow as its leader, and the Nisei translators were Kay Futamase, Mike Hori, Moffet Ishikawa, Hisashi Komori, Kay Tamada, Shizuo Tanaka and Shogo Yamaguchi.

Sgt. Moffet Ishikawa interrogating a Japanese prisoner

Moffet Ishikawa was at Negros Island when he heard that Japan surrendered.

As he mentioned in part 3 of his 2010 interview, he returned back to Panay Island to take part in receiving the Japanese surrender in Panay Island.

He also mentioned in that interview that he has a photo of himself writing as he was interviewing the surrendering Japanese troops.

Moffet Ishikawa oral history interview, part 1 of 3, March 18, 2010

Moffet Ishikawa oral history interview, part 2 of 3, March 18, 2010

Moffet Ishikawa oral history interview, part 3 of 3, March 18, 2010

See also:

Looking Back: A Japanese American Soldier Returns Home.

Moffet M. Ishikawa Obituary.

Col. Raymund G. Stanton

Col. Raymund G. Stanton (Col. Raymund Gregory Stanton) was born in Fort Hancock, New Jersey.

He's the son of Mr. and Mrs. William J. Stanton of 24 William Street, Fords, New Jersey.

Col. Raymund G. Stanton graduated in 1927 from the United States Military Academy (USMA), also known as West Point. It appears from the signing photo that Col. Stanton was wearing his West Point class ring while accepting the surrender in Cabatuan.

His brother, Col. Walter C. Stanton, belonged to West Point Class 1926. His uncle, Col. Hubert G. Stanton, to West Point Class 1911. A fourth member of the family, his nephew Walter C. Stanton Jr., graduated from West Point in 1950.

He was a veteran of the Pacific Theater from New Guinea to the Philippines.

He's a recipient of the Legion of Merit (G.O. 22, AFPAC 6/29/1945).

---

Raymund G. Stanton

USMA Class 1927 • Cullum No. 8218 • Jul 01, 1977 • Died in Columbia, SC

Interred in West Point Cemetery, West Point, NY

Colonel Raymund G. Stanton, (United States Army-Retired), died at his home after a long illness.

Colonel Stanton was born in Fort Hancock, New Jersey, and was graduated in 1927 from the United States Military Academy with a Bachelor of Science Degree. During his Army career he also graduated from the following schools: Regular Infantry School, 1936; Infantry Tank School, 1937; Command and General Staff College, 1941 and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces in 1952. He was an instructor in the Armed Forces Staff College in 1952 and 1953.

Prior to his retirement in 1957 after 30 years of service, Colonel Stanton served in all sections of the United States and in Panama, Puerto Rico, New Guinea, the Philippines, Korea, Japan, China and Europe.

During World War II he was Deputy Chief of Staff of X Corps in New Guinea, and in the Philippines he served at Leyte, Samar, Panay and Negros as regimental commander of the 126th Infantry of the 32d Division. He also served as commander of the 160th Infantry Regiment of the 40th Division.

In Korea from 1946 to 1947, he served as regimental commander of the 20th Infantry of the 6th Division and in Japan he served as the regimental commander of the 34th Infantry, 24th Division. He also served as port commander of the Port of Pusan in Korea.

Among his awards were the Silver Star, awarded for gallantry in action and the Purple Heart for wounds received on Leyte in November 1944, and the Bronze Star Medal for achievements connected with military operations on Negros Island on 15 May 1945.

He also was awarded the Legion of Merit for performance of outstanding services on Negros Island between 8 March and 1 May 1945 and the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster for services in the Philippine Islands and Korea from 1 July 1945 to 15 January 1946. Ht was also recognized for services in organizing and directing over one million Korean and Japanese refugees in Korea.

During the early period of World War II, Colonel Stanton was assigned as assistant G1 of the Army Ground Forces and implemented the personnel policies which facilitated the rapid expansion of the Armed Forces. Later, as G1 and as Deputy Chief of Staff of X Corps he contributed to the success of the combat in the South Pacific.

Following the war. Colonel Stanton became Chief of the Procurement and Separation Branch in the Personnel and Administration Division of the Department of the Army General Staff.

He came to Columbia as Chief of the South Carolina Military District in 1955, and then served as Inspector for Training at Fort Jackson. After retirement he remained in Columbia where he was a member of St. Joseph's Catholic Church.

He was a member of the Columbia Drama Club, the Palmetto Club, the Retired Officers Club of Columbia, the West Point Society and the Army-Navy Club of Washington.

Surviving are his widow, Mrs. Mary Henderson Stanton; a son, Brendon Paul Stanton of Los Angeles; a step-daughter, Mrs. Samuel C. Miller of New York (the former Rosetta Averill of Columbia), and a brother, Colonel Walter C. Stanton of Washington, D.C.

Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis

Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis (Rear Admiral Ralph Otis Davis) graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1914 as the president of his class.

He had served on several battleships and submarines, as well as heavy cruisers.

He was promoted Commander on 30 Jun 1935.

He was promoted Captain on 1 Jul 1941.

He commanded the USS Chicago (CA 29), a heavy cruiser, from December 1942 until it sunk on January 30, 1943 in the Battle of Rennell Island in the Solomon Islands, when it was attacked by Japanese aerial torpedoes during the Solomon Islands campaign. He received a Bronze Star medal for valor in the campaign.

He commanded the USS New Orleans (CA 32), another heavy cruiser from 14 Apr 1943 to 4 Jul 1943.

He was promoted Rear Admiral in July 1943.

In 1943, he organized the Amphibious Training Command, Pacific Fleet, and was its commander until 1945.

In 1945, he was in command of the 13th Amphibious Group, U. S. Pacific Fleet, in Western Pacific Operations.

The 13th Amphibious Group was tasked in September 1945 to transport the 40th Infantry Division from Panay Island to Korea for occupation.

In 1946, he was the Commander of Amphibious Group 2, U. S. Atlantic Fleet.

From 1946 to 1948, he was the Commander of Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet.

His last post was in Norfolk, Va. where he was the commandant of the Fifth Naval District from 1948 to 1953. He was appointed to this post on November 30, 1948.

He retired from the Navy in 1953 with the rank of Vice Admiral after 42 years of service.

His decorations include the Legion of Merit (Army) with 2 gold stars from Navy; Mexican campaign (Vera Cruz) Victory with star; American Defense with star; American Area Campaign, Asiatic-Pacific Area Campaign with star and Philippine Liberation medals; Bronze medal with combat V; Commander Order of British Empire.

Following his retirement, he served for several years as executive administrator of the Episcopal diocese in southern Virginia.

Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis was born on January 19, 1891 in Litchfield, Montgomery County, Illinois.

His parents were Edward Richard Davis and Mary Gertrude Grubbs Davis.

His siblings were Ella Ferne Davis Lewis (1880–1932), Frances Mary Davis Talcott (1885–1962), Edward Paul Davis (1887–1888), Louise Davis Yaeger (1895–1973) and Edward Richard Davis Jr (1901–1954.)

He was married twice. His first wife, the former Anita Cresap (Annita Bithia Cresap Davis ), of Annapolis, died in 1922. The former Dorothy Benson (Dorothy Benson Davis), his second wife, died in November, 1966.

His children were Ralph Cresap Davis, of Annapolis; Otis Benson, of Kent, Conn.; and LCDR Frank McDowell Leavitt Davis, who died in 1946.

He died at Portsmouth Naval Hospital after a short illness in 1967. He was 76.

He's buried at the U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Md. (United States Naval Academy Cemetery, Annapolis, Anne Arundel County, Maryland.)

Tech. Sgt. Terno Odow

T-Sgt. Terno Odow was born on May 20, 1920 in Moyer Junction, Wyoming, near Kemmerer, Wyoming.

His parents were Kanichi Odow (Gonichi Kanichi Odow) and Haruye Kataoka of 134 Mead Street, Salt Lake, Utah.

His siblings were Masako Odow Taku (Masako Taku) of San Jose, CA; Toshi Odow (Toshiko Odow) of Salt Lake City, UT; Fusaye Peck (Fusaye Odow-Peck) of Saugus, CA; Fumi O. Toma (Fumi Odow-Toma, Fumiko Odow, Fumiko Odow-Toma, or Fumiko Toma); and Richard Odow of Roy, UT.

His wife was Rosa S. Odow.

He attended high school in Rexburg, Idaho where he was very active in track and field sports and held the title of State of Idaho champion in the low hurdles competition for many years.

He speaks fluent Japanese, having spent two years at Keio University, Tokyo, before the outbreak of the war.

After discharge from the military service, he attended and graduated from the University of Utah, receiving his degree in Business Administration.

He was employed by Ponder & Best in Denver, CO and later was transferred to Southern California to become Vice President of said company and remained until retirement.

He was an avid golfer in California and also served as President of the Optimist Club.

He passed away on September 11, 1999 at Holy Cross Hospital in Los Angeles, California.

He's buried at Los Angeles National Cemetery, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California, USA.

Frank Patrick

Franklin Edward Patrick

By Staff Writer on August 15, 2014

Mr. Franklin Edward Patrick was a native of Ft. Gaines but had lived in Barnesville for most of his life.

He was the son of the late Mr. Hugh Franklin Patrick and the late Mrs. Julia Elizabeth Herman Patrick and was also preceded in death by his first wife, Elaine Leverett Patrick; by his brother, Oscar Herman Patrick; and by two sisters, Sarah Michael and Aurellia Craig.

Mr. Patrick was a graduate of Gordon Military High School and attended Gordon College. He was truly a self-made man. Early in adulthood, he studied welding as an apprentice who wanted no payment other than the knowledge and training that he could receive. His first project was to build himself a wood lathe which was the beginning of a lifelong passion in woodworking and woodturning. Mr. Patrick started his own business and became the founder of the local woodturning group. His first large job was the staircase in the Governor’s Mansion in Atlanta in which all of the spindles were turned by hand. Among other examples of his work is the carousel at Six Flags Over Georgia. He even held a Guinness World Record for the largest hand turned wooden bowl in the world. Mr. Patrick was also employed by the city of Barnesville where, over the years, he served in several capacities including city zoning administrator and water works superintendent.

Mr. Patrick was a veteran, having served in the U.S. Army in both World War II and in the Korean Conflict.

He was a Mason for the past 60 years and was a member of Pinta Lodge 88. Mr. Patrick was a member of the First Baptist Church of Barnesville where he had been a deacon.

Mr. Patrick, age 88, of Barnesville passed away Aug. 14, 2014 in an Upson County healthcare facility.

Survivors include his wife, Dorothy “Dot” Patrick; four children, Franklin E. Patrick and Christie) of Pooler, Gail Rooks (and Ricky) of Barnesville, Hugh Patrick (and Carole) of Barnesville and Linda Patrick of McDonough; three stepchildren, Tom Torbert (and Margaret) of Marietta, Johnny Torbert (and Nadine) of Barnesville and Christy Caldwell (and Bill) of Nashville, Tenn.; two brothers-in-law, Edgar Wright of Charlotte, N.C., and Wayne Leverett (and Vicky) of Savannah; five grandchildren, Tim Rooks (and Lauren) of Barnesville, Ryan Rooks (and Amber) of Barnesville, Heather Metcalf (and Donald) of Jacksonville, Fla., Wilson Patrick of Jacksonville, Fla., and Jason Dixon of Pooler, Ga.; five step-grandchildren; five great-grandchildren; 12 step-great grandchildren; and two step-great-great grandchildren.

He's buried at Greenwood Cemetery Barnesville, Lamar County, Georgia.

See https://barnesville.com/franklin-edward-patrick/.