10.1 Army Messenger

Around that time, news from the United States after the occupation of Okinawa was all about the bombings of Japan proper. We also learned of the surrender of Germany from the US military leaflets that said ‘A black cloud has come to the East’. With the start of the rainy season, the mood at the Bocari position was gloomy. Each unit held variety shows to liven up the atmosphere.

While we tried to adapt, the lack of food and salt became a serious issue. In search of food, we had to go further and further away from our positions. Sometimes, these forays involved encounters with the Philippine Constabulary. The rainy season also made it difficult to collect food. On August 13, ‘Corporal Nakagami of the wireless radio squad reported, ‘US broadcast says Japan has made a request of the Allies through Switzerland that she would surrender without conditions.’ I gave a strict order not to tell anybody, and to carefully listen to the news on the following days.

Then, the Emperor’s broadcast of unconditional surrender on August 15 came. I myself listened with the receiver on my ears and immediately reported the news to Colonel Tozuka. He quickly assembled the company commanders and told them the news. Instead of grieving over the surrender, the whole atmosphere at Bocari regained brightness. The faces of the soldiers of relief and the joy of liberation. That night each unit got out the best preserved foodstuffs and ate to their hearts’ content. The Japanese Army in Panay was at last going to be relieved of the day and night combat that they had endured for more than three years.

On that same day, however, our only communications engineer Corporal Takada of the headquarters’ wireless squad went missing when he left to look for food. The last news of him was that he got embroiled in a fight with soldiers at a village. He was killed in battle on the day the war ended to become the last of the unit’s casualties of the war in Panay.

With news of the surrender, the unit regained cheerfulness and some talked of returning to Japan. Nonetheless, there were also some voices fearing retaliation for atrocities committed by us on Filipinos. I myself was concerned about the clause in the Potsdam Declaration that said that those who killed or maltreated Allied POW and non-combatants would be tried at court. I asked Colonel Tozuka about it and he just laughed saying that it was meant for those who committed awful slaughter, and therefore, had nothing to do with us.

The Kempeitai commander, Captain Kaneyuki Koike, got out manual of the Army Criminal Law and opened to the pages near the end of the book. He went through the international agreements and read aloud the important articles based on the Geneva Convention on the treatment of POWs. Though I had heard of the existence of such agreements, it was the first time I heard about their content. I could not satisfy myself by just listening to them. Consequently, I read the articles on my own to the extent that I was able to talk to others about them. Colonel Tozuka then prohibited everyone from leaving his assigned position, not even a single step. He especially warned everyone not to have any conflicts with local residents.

We expected that some instructions would come from the US forces. On August 24 or 25, a US observation plane flew over Bocari, as though looking for us. We spread a signaling panel and sent signals to the US plane. Recognizing the signaling panel, the plane’s body swung left and right and dropped a communication tube. Inside were instructions of the date and place where a representative of the Japanese Army was to proceed. There was also a written order signed by staff officer Hidemi Watanabe (then in Negros), which said, ‘By the order of General Yamashita, commander of the 14th Area Army, the Japanese Army should obey the instructions given by the US forces in your locality. On the next day, the observation plane flew back. When we signaled the reply, ‘We have understood the instructions,’ the plane dropped a walkie-talkie (transceiver) to be used for contact.

That day, the unit commanders’ meeting decided that, as previously planned, the Japanese Army emissaries would be Captain Koike of the Kempeitai, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I, with Sergeant Matsuzaki as the interpreter. The NCO cadet platoon led by 1st Lieutenant Horimoto, with Private First Class Ueki as the interpreter, would accompany us as our escort.

Early in the morning of August 30, the emissaries of the Japanese Army in Panay, Captain Koike, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I, climbed down from Bocari and walked towards the town of Maasin. Moving in front, Private First Class Ueki carried a big white flag. As we advanced, the observation plane came to meet us. Sergeant Matsuzaki kept in touch using the walkie-talkie. The mountain path widened to a road along the river as it was nearly the set time of our arrival at the appointed place. As we advanced, we were expecting some contact from the US forces. Suddenly, seven or eight gigantic American soldiers came out of the jungle and surrounded us.

With a smile on his face, a gentle-looking officer of around 34 or 35 years of age told me that they had come to meet us. He was wearing the insignia of a major. The Major walked cheerfully along with me, as if he were escorting a group of children. As we moved along the river, the jungle came to an abrupt end and the surroundings suddenly became bright. We were at Daja, the reservoir of Iloilo City’s water supply. Immediately, a dozen news cameras positioned in front of us started to roll. Some American soldiers who surrounded us also clicked the shutters of their cameras. The extraordinary scene that all of a sudden materialized took us all aback. All the American soldiers before us were full of joy and the scene was like that of a festival.

Our escorting NCO platoon stood by while the four of us – Captain Koike, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa, I, and the interpreter Sergeant Matsuzaki – were placed on jeeps. I rode with a battalion commander with a platoon of US soldiers guarding our front and back. Our jeeps ran through the forest, and in about five minutes, we could see houses of local residents. Citizens who recognized us came rushing towards the vehicles, following us while shouting all sorts of curses in anger – ‘bakayaro,’ ‘dorobo’ (stupid, thief). Some raised their fists, some mimicked beheading with their hands, and a raging crowd surrounded us. The jeering reached its height as our jeeps arrived at Maasin plaza.

At an open space of about 150 square meters, heavy machine guns were set at all directions while around a battalion of soldiers were on strict watch. As if waiting for a theatrical performance around the plaza, hundreds of local people stayed for the start of the meeting between the Japanese Army emissaries and the representatives of American forces. After the four of us were body-checked, the battalion commander escorted us to a table positioned at the center of the plaza. At the center of the table sat a dignified colonel of around 45 or 46 years old. Along with three or four more young officers, a shrewd-looking young Lieutenant Colonel sat on his left and a major of around 50 years of age sat on his right. Behind them stood the bearers of the US and the regimental flags while around 20 colossal soldiers surrounded them in a half circle.

Only the young Lieutenant Colonel on the US side and myself on the Japanese side attended to the technical details related to the surrender. Having experienced the acceptance of POWs at the capture of Bataan Peninsula, I replied in detail to questions such as the number of Japanese Army members, the number of patients, and weapons at Bocari. As a whole, the talk concluded smoothly, although there were a few points on which we did not agree.

During the discussion, I pointed out that we were shot at by Filipino soldiers and civilians on the way down to surrender and requested for a guarantee that such behavior would not be repeated in the future. The US side promised they would be responsible for our safety. I also asked for transport vehicles for all the Japanese soldiers secured by the American forces as well as special transport and hospitalization for the patients. To our surprise, they readily accepted these requests without hesitation. For 100 headquarters officers and the rest of the unit, the agreed date of surrender was September 1. The surrender of the Saitô unit was to follow on September 2.

Colonel R.G. Stanton (commanding officer of the 160th Infantry Regiment) signed the instrument of surrender on the US side, and Captain Koike on the Japanese side. Just when the signing was finished, it suddenly became calm. With the command, ‘Ten hut!’ Colonel Stanton and the others all stood up and saluted. As we turned together and saluted, we saw a noble Major General of around 50 years of age, who had a face like a young boy, followed by his staff. He was smiling contentedly and repeatedly returned our salute. A Japanese-American interpreter standing close to me whispered it was the 40th Division Commander, Major General Rapp Brush.Davis

|

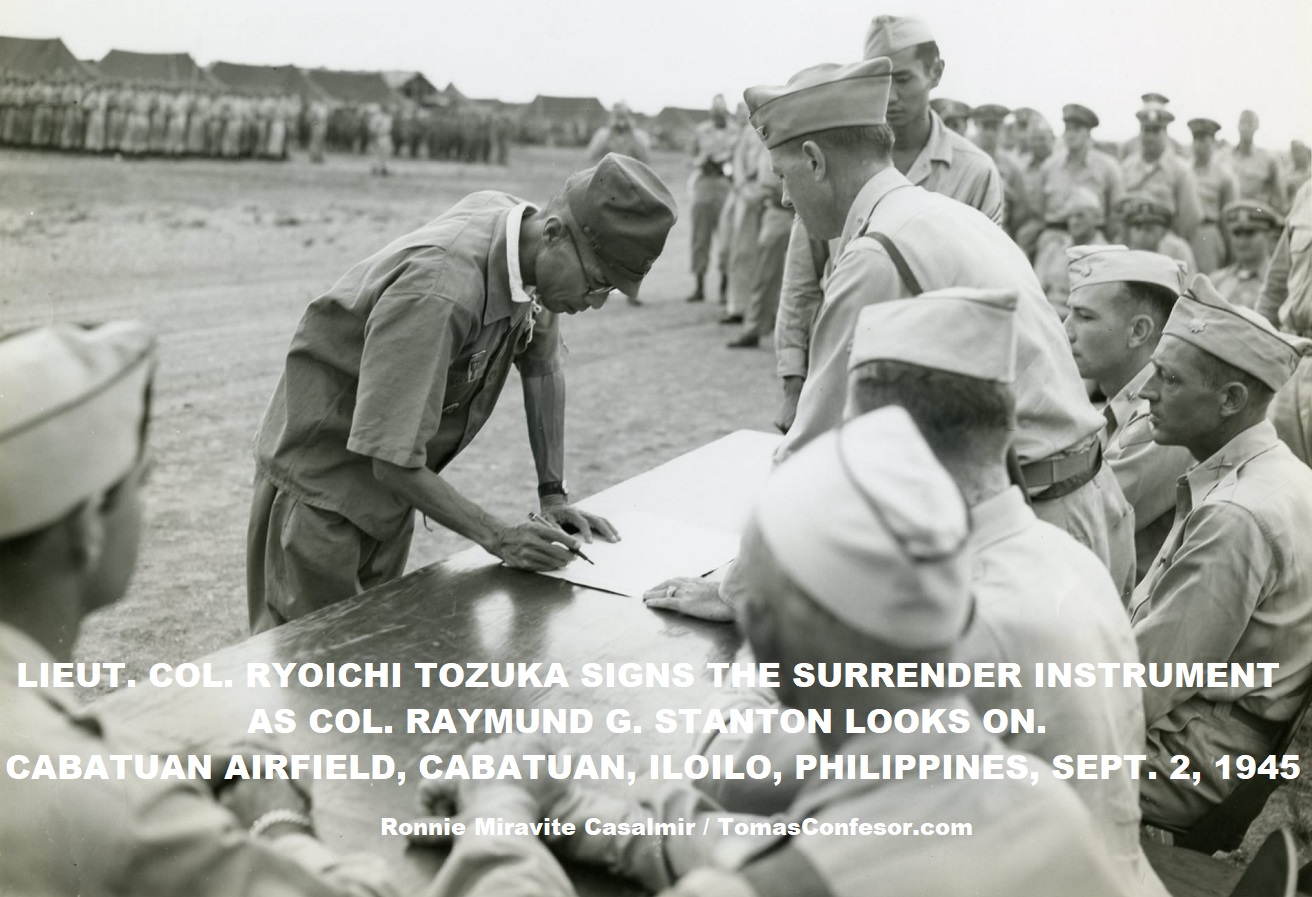

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: Davis This must be the ending of the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945 that Kumai had mistakenly placed here. Kumai had mistaken Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis (a two-star admiral) for Maj. Gen. Rapp Brush (a two-star general). (See surrender signing ceremony) Major General Rapp Brush had already been replaced by Brig. General Donald J. Myers as commander of the 40th Infantry Division a month earlier, in July 1945, (Brush returned to the U.S.), so Gen. Brush could not have been present anymore at this Maasin meeting, and Myers was only a one-star brig. general, and from his photos, Gen. Myers wasn't young looking. On the other hand, at the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2 1945, there was somebody there who fitted the bill, a young looking two-star officer, in the person of Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis, who had arrived only the day before, September 1, 1945, aboard his flagship USS Estes, so Davis could have been only at the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield and not in the Maasin meeting in August. During the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis can be seen in the photos as being seated at the side. Most likely, after the signing, when he stood up, that's when "ten hut" was called. Rear Admiral Davis and his 13th Amphibious Group were in Iloilo to transfer the 40th Infantry Division to Korea for occupation. This transfer began with the ship LSD Carter Hall being the first vessel to depart Iloilo five days later, on September 7, 1945, with the advance party of the 40th Infantry Division and elements of the 532nd EB & SR. The rest of the division followed on other transport ships. Control of the Cabatuan Airfield POW camp was turned over to the 658th tractor battalion that same day, September 7, 1945 At the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945, the instrument of surrender was signed by the overall Japanese commander Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka for the Japanese, and by the 160th US Infantry Regiment commander Col. Raymond G. Stanton for the Americans and Filipinos. Protocol dictates that a surrender be received by an officer of about the same rank and position, and so Col. Stanton was designated to receive even though his superiors were also present.

|

We ended the meeting with our request to give the surrender instructions to the Saitô unit. On the way back, the people along the road kept shouting but I noticed their faces were full of joy as they must have known of the surrender of the Japanese Army. On our way back to the mountains, the US observation plane saw us off from above but we did not hear any gunshots.

We reached the Bocari headquarters around 3 p.m. Colonel Tozuka and other commanders were eagerly waiting for our return. The three of us immediately reported to them the details of the meeting with the American forces and the disturbances made by the local people along the road on our way to and from the surrender site. We pointed out that the US forces were kind and courteous, more than we had expected. Alcoholic beverages made from corn were offered for celebration. The commanders immediately left without touching them, however, to tell their men of the developments. A joyous and relieved atmosphere soon filled the whole mountain of Bocari and the soldiers of the headquarters were excited like children going on an excursion. The officers and men of Panay were so exhausted that they could not afford to grieve for the defeat of their country.

10.2 Entering Prisoner of War Camp

August 31, 1945 was the last day for the headquarters members’ stay in Bocari. We cooked the best foods of the mountain and ate to our hearts’ content. It had been more than five months in the Bocari position. The mountains that protected us seemed very familiar to us and we knew that we would miss them. To remember the mountains that we would not come back to again, we asked a soldier who used to be an art teacher of junior high school, and another one who liked painting, to draw the mountains. Colonel Tozuka got one of the pictures, and I received the other.

We had several Filipinos who served as spies, mercenaries, and servant boys, but I had told the US forces that there were no Filipinos with us. For this reason, I told the Filipinos with us that we were going to surrender by the order of the Emperor. Giving each one of them a carbine and plenty of food, we allowed them to go wherever they wanted. In the morning of September 1, Colonel Tozuka and all others attached to the headquarters descended along the path we took as emissaries and looked back at the mountains of Bocari, but we heard no gunshots this time.

The US forces did what they had promised. The observer plane flew low as it came to meet us. Eventually we arrived at Daja, east of Maasin, where we arrived as military envoys. At the entrance of the open space, around 20 moving cameras started to run at once while a line of newspaper cameras and those of US officers clicked away simultaneously. This unexpected and abnormal scene embarrassed Colonel Tozuka and the soldiers of the headquarters.

Two companies of American troops guarded the open space surrounded by the jungle and a few Filipino officers were also there. At the long center table sat the officers such as Lieutenant Colonels and Majors, with Colonel Stanton at the center. Behind them, around 30 guards were standing. Following the instructions of an American officer, the unit commander, Colonel Tozuka, was the first to walk through two rows of American soldiers and handed over his sword and pistol. Colonel Stanton received them with a solemn expression on his face. Following him, Captain Koike, and the six of us officers attached to the headquarters, handed over our swords. Colonel Stanton ceremoniously received them as if performing in a play. It was the ritual of surrender. Without weapons and having nothing to do, the unit commander was the figure of a defeated officer. (I later came to know that Colonel Tozuka’s sword was handed down to Major Ramon C. Gelvezon, executive officer of the 63rd Regiment.) NCOs and soldiers also handed over their weapons and bullets to the American soldiers who stood in rows. A thorough body-check along with belongings was also carried out.

After the ceremony, we went out onto the asphalt road via Maasin under the strict guard of US soldiers: the officers in jeeps and the soldiers in trucks. As we came into populated areas, people crowding along the road shouted loudly, ‘Bakayaro’, ‘Dorobo!’ The commotion built up and endangered us since some residents started to throw stones at our vehicles. The vehicles pushed their way through the crowd with the US escorts shouting and firing warning shots into the air.

The vehicles stopped at the former Japanese Army airfield in Cabatuan. Tents were built in the 200 square-meter POW camp surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. US soldiers were on duty in the watchtowers. As we watched, local residents congregated around the fence, shouting like mad and throwing stones. They pushed forward until it seemed that the fence would break; American soldiers shot into the air to threaten them off. The crowd would briefly withdraw but soon gathered again. Such uproar lasted until the evening. Because of the stone throwing, we could not get near the edge of the camp.

Contrary to the harshness surrounding us, the four or five US officers who were in charge of us were very kind. They readily and smilingly helped us set up tents or dig ditches around them. They even offered us a helmet full of candies in the evening.

EARLY MORNING TO MID-MORNING, SEPTEMBER 2 1945

September 2nd was the day of surrender for the other Japanese soldiers. From early morning, the local people surrounded the camp, shouting loudly and throwing stones. By mid-morning, there was a continuous flow of arrivals of former Japanese soldiers as POWs. Tents for twenty were set up one after another all around the site.

A LITTLE AFTER NOON, SEPTEMBER 2 1945

The next day*, a little after noon, all officers were assembled to attend the surrender ceremony. As we made our way to the setting of the ritual, we saw US soldiers feverishly checking out the belongings of Japanese soldiers who descended from trucks. Every one of them had gotten rid of weapons and they were running around in confusion amidst the shouting of US soldiers. The elite troops of Panay already looked quite like POWs.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: *By "The next day" here, Kumai must have meant the next day after they arrived at Cabatuan Airfield, not the next day after |

The venue for the surrender ceremony was a corner of the airfield beside the camp, where hundreds of military vehicles were parked. A battalion of US troops and a company of intrepid-looking Filipino Army personnel were standing in rows. I carefully observed the behavior of the Filipino soldiers against whom we had fought. In following orders, no movement of theirs looked inferior to that of the American soldiers, making me think of the hard training they must have received.

At the center was a stage where Colonel Stanton stood. Representing the Japanese Army, the Tozuka unit commander loudly read out the statement of surrender of the Japanese Army to the US Forces. As expected from the look of the setting, the ceremony ended rather simply.Davis (See Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield)

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: Davis What Kumai remembered had happened here, he mistakenly placed at the surrender negotiations 5 days before: "Just when the signing was finished, it suddenly became calm. With the command, ‘Ten hut!’ Colonel Stanton and the others all stood up and saluted. As we turned together and saluted, we saw a noble Major General of around 50 years of age, who had a face like a young boy, followed by his staff. He was smiling contentedly and repeatedly returned our salute. A Japanese-American interpreter standing close to me whispered it was the 40th Division Commander, Major General Rapp Brush." Kumai had mistaken Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis (a two-star admiral) for Maj. Gen. Rapp Brush (a two-star general). (See surrender negotiations) Major General Rapp Brush had already been replaced by Brig. General Donald J. Myers as commander of the 40th Infantry Division a month earlier, in July 1945, (Brush returned to the U.S.), so Gen. Brush could not have been present anymore at the surrender negotiations on August 28, 1945,, and Myers was only a one-star brig. general, and from his photos, Gen. Myers wasn't young looking. On the other hand, at the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2 1945, there was somebody there who fitted the bill, a young looking two-star officer, in the person of Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis, who had arrived only the day before, September 1, 1945, aboard his flagship USS Estes, so Davis could have been only at the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield and not in the Maasin meeting in August. During the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis can be seen in the photos as being seated at the side. Most likely, after the signing, when he stood up, that's when "ten hut" was called. Rear Admiral Davis and his 13th Amphibious Group were in Iloilo to transfer the 40th Infantry Division to Korea for occupation. This transfer began with the ship LSD Carter Hall being the first vessel to depart Iloilo five days later, on September 7, 1945, with the advance party of the 40th Infantry Division and elements of the 532nd EB & SR. The rest of the division followed on other transport ships. Control of the Cabatuan Airfield POW camp was turned over to the 658th tractor battalion that same day, September 7, 1945. In the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945, the instrument of surrender was signed by the overall Japanese commander Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka for the Japanese, and by the 160th US Infantry Regiment commander Col. Raymond G. Stanton for the Americans and Filipinos. Protocol dictates that a surrender be received by an officer of about the same rank and position, and so Col. Stanton was designated to receive even though his superiors were also present.

|

As we returned to the camp, more and more Japanese POWs as well a Hôjin women and children arrived. The treatment of high-ranking office was different from that of the rest of the POWs. The officers were put in small tents for two while NCOs and ordinary soldiers were in large tents for twenty. Thus, we observed for the first time how the Geneva Convention was supposed to be carried out.

10.3 Driven Away with Stones

In the camp, we were surprised at the delicious food prepared for us but four or five days later, its quality suddenly deteriorated. This was because the 40th Division of the US Army that was in charge of the camp was reassigned for posting in Korea. The night before their departure, 2nd Lieutenant Jones and other officers in charge of the camp came to visit us. It seemed as though they would miss us who had joined in the fighting in Bocari.

Soon after, I checked the captured survivors against the roster of the whole unit made before the US landing. There were 1,560 survivors. Therefore, those killed in battles after the US landing numbered around 850. Around 120 Hôjin survived while the number of those dead was around 70 to 80.

The Tozuka unit POWs left for the camp in Leyte around 4 p.m. on September 15. We left the Cabatuan camp in a long line of trucks. Filipino citizens, high school students of lloilo shouted and threw stones at us.

From the second floor window of a house in front of the Iloilo Provincial Capitol, the wife of Dr. Daniel Ledesma, a German lady, was staring down at our vehicle. Only this lady seemed to see us off with compassion.

The row of our trucks managed to get through the turbulence in Iloilo City and reached the Iloilo harbor. We felt relieved and got on board the transport. Quite a number of the soldiers seemed to have been injured by the stones thrown at us and were being treated on the ship. It was only when I was aboard that I was able to take a relaxed look at the city. With lights twinkling in the evening, Iloilo City was beautiful. This was the city where, for more than three years, I left various memories of my youth. Although the citizens cursed us and drove us away with stones, I could never forget fallen soldiers and Hôjin and my affection for the city. I stood on deck until the lights of Iloilo were no longer visible. Thus, I said goodbye to the war dead and Iloilo in tears.