6.1 Executions of American Civilians

In December of 1943, as the punitive force was moving south along a tributary of the Aklan River, we bumped into a bushy-bearded American. He was in a torn pair of shorts, bare-footed and limping. Captain Watanabe himself sternly interrogated this man. He identified himself as Mr. King, and said, ‘I used to be a guerrilla officer, but with the Japanese punitive campaigns, my unit scattered. Since I am conspicuously an American, neither the guerrillas nor the locals want to take me in. So I have been wandering along the river.’ From what he said further, Captain Watanabe found out there were more Americans near Egue close to the town of Tapaz, 13 kilometers north of Calinog.

Watanabe immediately dispatched the whole company to Egue and found more than 10 Americans in the village, including a couple of around 50 years of age and their son of 12 or 13. From their interrogation, we learned that there were still more Americans further in the mountains, and my platoon was sent to capture them.

The men were already exhausted, but I encouraged them. We strained to march in the dark, sometimes crawling as we made our way with a local resident as guide. When we reached the village, all residents, including the Americans, had already disappeared. We managed to return to the field headquarters at midnight and slept like the dead under the hut. Next morning, when the company was getting ready, there were no Americans in sight. I asked an NCO attached to the unit headquarters, and he told me, ‘Captain Watanabe executed them all.’ I had thought that all the captured Americans would naturally be sent to the internment camp in Manila, so I felt furious about the cruel approach of Captain Watanabe. On hearing the story, my subordinates were all compassionate and outraged: ‘How could he kill the family of three since they were obviously civilians?’

Neither the Battalion Commander Ryoichi Tozuka nor Captain Kengo Watanabe said anything to anybody about the execution of the Americans, probably because of pricks on their conscience. (Later on, I learned that it was Captain Watanabe who reported the capture to officers at the garrison headquarters in Cebu City and that he did the executions following their order. There were rumors that the order was to bury the fact that – unknown to others, including the Manila headquarters – they wanted to avoid the complexity of formal procedures in dealing with these persons and their transport to Manila.)

In March 1946, at the camp for war criminal suspects at Nichols Field, Second Lieutenant Otsuka informed me that this unpleasant incident was big news in the United States and led to the submarine rescue of the remaining Americans in Panay. It caused such strong hatred for Panay war criminal suspects among the American public such that everyone involved was likely to be condemned for execution by the War Crimes Tribunal.

After the capture of the Americans in Egue in Tapaz, we made our way back to Iloilo City on December 31, destroying guerrilla bases along the way.

The companies of Yoshioka and Fujii, who had taken different routes to Kalibo, Capiz also returned to Iloilo through Pandan, Antique. In the mountains near the town of Pandan, the Itsuki squad of 1st Lieutenant Fujii’s company arrested a guerrilla captain, Antonio Romero. He had three daughters, well-known beauties throughout the province of Antique. Impressed by their beauty, staff officer Watanabe insisted that the Nihon Boseki Kaisha (Japan Spinning Company) in Iloilo employ all three.

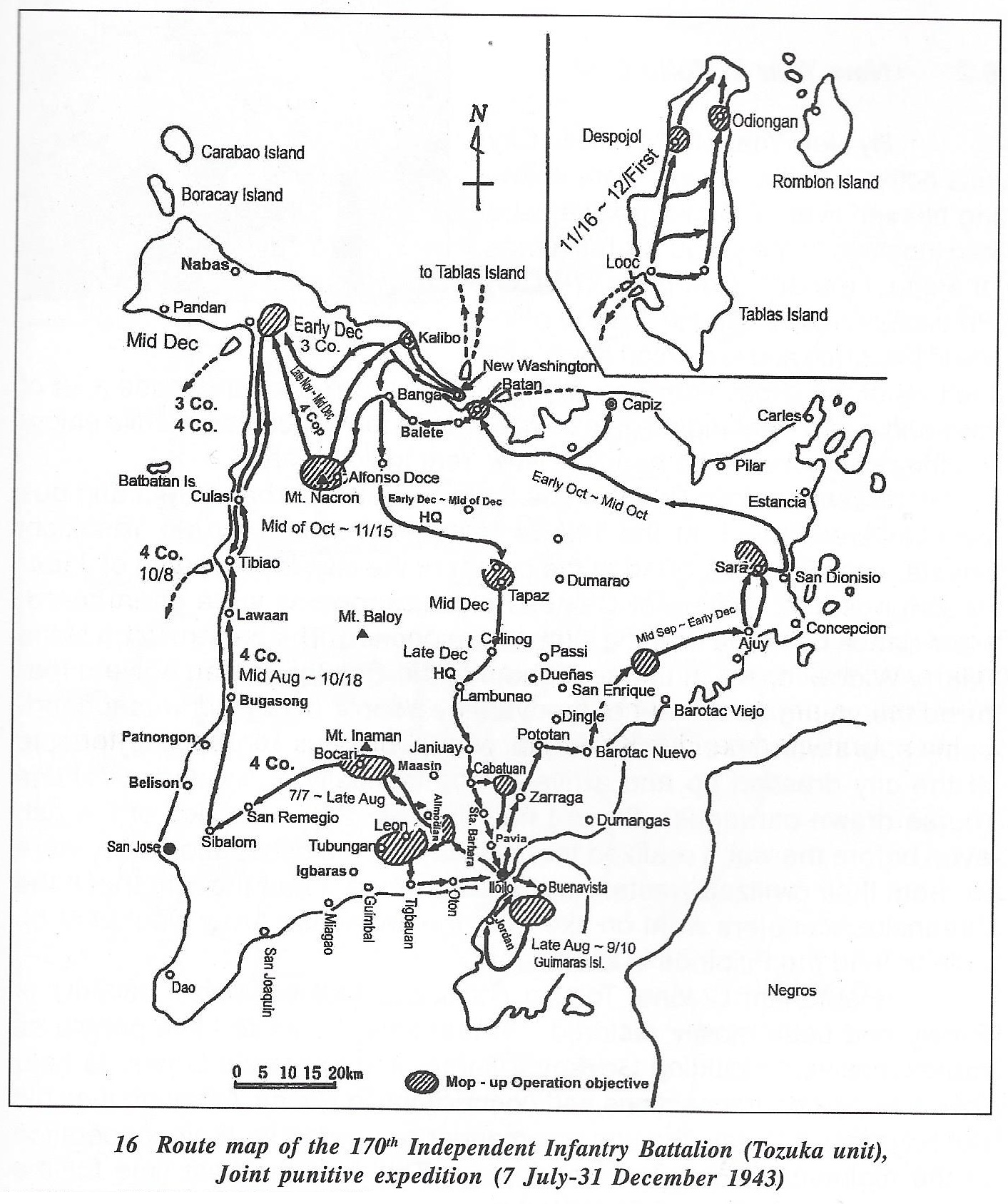

Thus, the relentless punitive expedition that lasted for a half-year before Manila headquarters announced the subjugation of the Panay guerrillas. The Taga unit was ordered from Antique to Davao on Mindanao Island on December 20, and the 4th Company of our unit led by Yoshioka was sent to replace them in Antique.

During the expedition, the Tozuka unit obtained 1,000 weapons (including some hand-made ones), 10 wireless radio sets, and around 70 guerrilla officers and men. Behind the rather brilliant results, there were numerous deaths of local residents and guerrillas.

A Filipino guerrilla account describes what happened:

It was a gruesome carnival of blood and fire that the Japs celebrated in northeastern Panay. The thoroughness with which they executed their campaign of destruction could be seen by the long rows of leaping flames at night. Houses and inflammable shrubs, talahib [tall thick grasses], and dried forests were ablaze. The bloodthirsty Japs cried for more blood.This account also provides records on the guerrillas: The number of the deaths of civilian residents was 10,042 between July and until the end of December 1943.

The Chinese evacuees at barrio Longao in Passi were rounded up and ordered to prepare a sumptuous banquet. After the Japs had their fill, the feat-stricken Chinese, numbering around eighty-six (86), were hog-tied and burned to death in the very house where the Japs feasted.

Corpses of men and women, and children were strewn along the mountain trails in Dumarao, Passi and Barotac Viejo.

In the municipality of Sara, only one person out of the entire population of a barrio survived the samurai [traditional Japanese sword].

In another massacre, forty-eight men, women and children who sought refuge in the last retreat atop the Yating mountains were ruthlessly murdered.

During this time, the guerrillas had been ordered by Mac Arthur’s headquarters to avoid major battles against the Japanese Army. The 6th Military District led by Colonel Peralta strictly observed this order because they lacked ammunition and weaponry. For the preservation of their forces and resources, they adopted the ‘Lie Low’ policy. This meant that the guerrillas hid behind the local people while being prohibited from leaving the area of their garrison. They threatened the local people with execution if they gave away information on the guerrillas to the Japanese Army who demanded it. Therefore, from both sides, the victims were the local residents.

Governor Confesor was critical of Colonel Peralta’s ‘Lie Low’ policy. It seemed childish since it only forced sacrifices on the part of common citizens. In effect, the guerrilla army was negligent or unable to protect the people being killed, avoiding even ‘small battles’ to help them. Hence, the two heroes of anti-Japanese forces in Panay were on bad terms, and later on, even caused the guerrilla hunt for Governor Confesor.

The Kinoshita unit in Capiz and the Taga unit in Antique fared badly in comparison with these accomplishments of the Tozuka unit. Both units saw little action during the expedition. For this reason, they had fewer victims and counted not as many deaths or wounded among their soldiers. Unit commander Kinoshita was sent back to Japan after the expedition since, apparently, his deeds did not satisfy the headquarters. Lieutenant Colonel Kanji Tanabe, who used to have conflicts with staff officer Colonel Watanabe at the Cebu headquarters, replaced him. Lieutenant Colonel Tanabe was my battalion commander during the capture of Bataan Peninsula.

The war accomplishments of the Tozuka unit made Captain Kengo Watanabe famous. However, contrary to his celebrity status outside, he was isolated within the unit.

At the end of December 1943, my unit – the Tozuka unit or the 37th Independent Infantry Battalion of the 11th Independent Garrison Unit – was reorganized and became the 170th Independent Infantry Battalion of the 31st Independent Mixed Brigade. With this reshuffle, there were significant changes in the make up of the battalion. Captain Kengo Watanabe, who tended to disagree with and confront other officers, angrily removed himself from the unit headquarters and became the first commander of the machine cannon unit of the battalion.

|

Lt. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka Panay garrison commander, commanding officer, 170th Independent Infantry Battalion |

6.2 New Year in Iloilo City

By New Year of 1944, Iloilo City was active and the citizens were enjoying relaxed lives. Colonel Tozuka, who had lodgings at the gorgeous residence of Panay Electric Company (PECO) President Mariano Cacho, invited officers to celebrate and to comfort them from the toils of the expedition. The young officers drank a lot and made a lot of fuss and noise – getting rid of frustrations from the expedition – while enjoying the peace. It was the happiest New Year in Iloilo City.

Between Iloilo City and the town of Santa Barbara, train and bus services were good. At the Tokiwa restaurant owned by Mr. Yosokichi Miyata, near Plaza Libertad at the center of the city, loud singing of Japanese tunes and reciting of Chinese classical poems were often heard. More dance halls and bowling alleys were opened. The performance of the ‘Merry Widow’ opera at the auditorium of the College of San Agustin featured the young daughters of the wealthy people of Jaro. It was a handsome opera with the accompaniment of an orchestra. High-society people of the city dressed up and arrived in fantastically decorated caromata (horse-drawn carriages). Since I had observed the lifestyles of the rich even before the war, I realized that the ways of the occupation army were far from their civilized western ways. Regretfully, I had thought that if the Japanese occupiers went on like that, the Japanese Army would not be able to lead the Filipinos in the future.

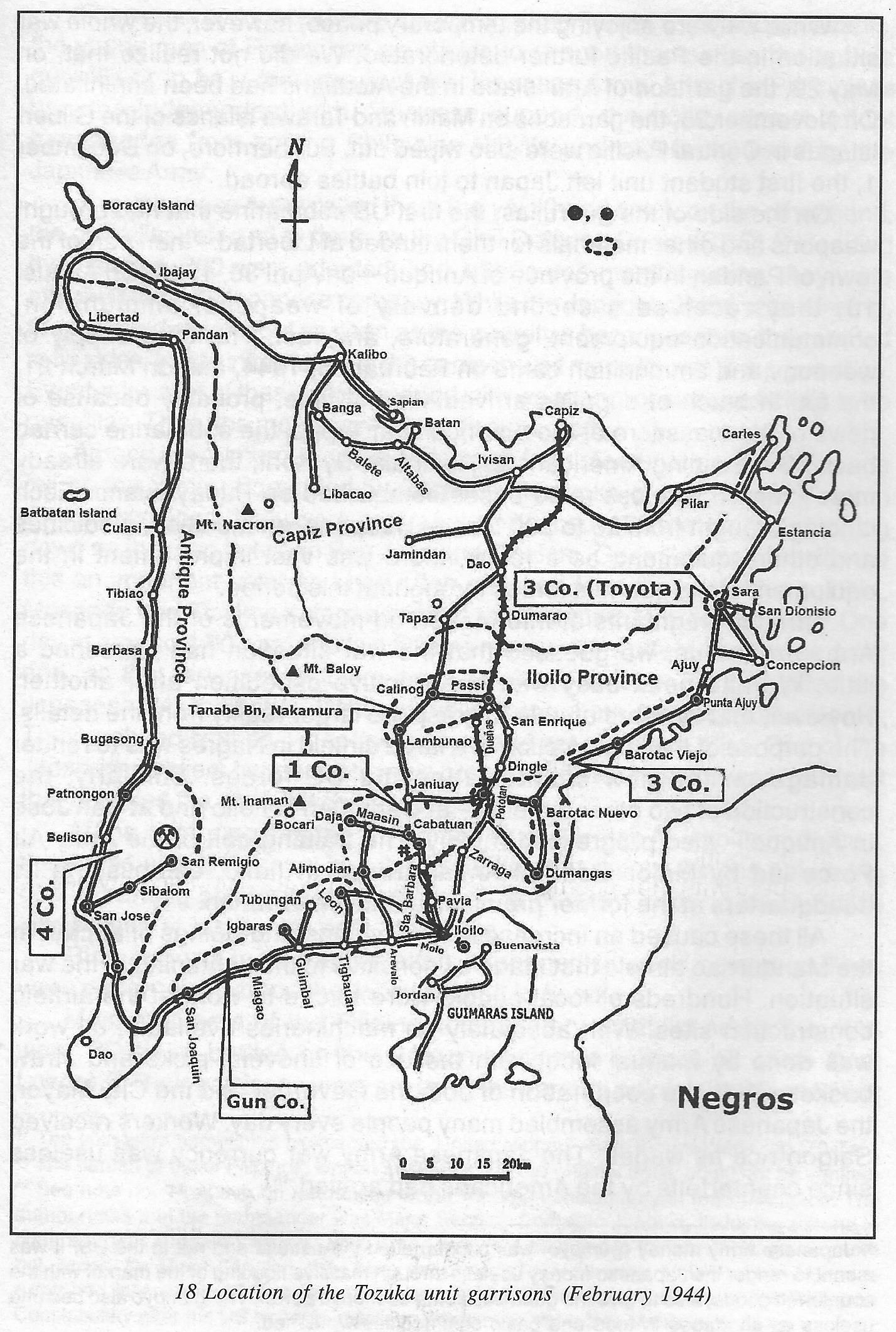

Lieutenant Colonel Tozuka concluded that the public security of Panay had been mostly restored. At one time, he invited five people as representatives, including Governor Caram and Fernando Lopez, to hear their opinions on transactions and connections in Panay. Although they did not have much to say, the unit commander requested for their cooperation in the maintenance of peace and order. This was the best time for the Japanese Army in Panay. The short period of peace – early in 1944 – saw the most numerous of its garrisons established across the island.

|

While we were enjoying the temporary peace, however, the whole war situation in the Pacific further deteriorated. We did not realize that, on May 29, the garrison of Attu Island in the Aleutians had been annihilated. On November 25, the garrisons on Makin and Tarawa Islands of the Gilbert Islands in Central Pacific were also wiped out. Furthermore, on December 1, the first student unit left Japan to join battles abroad.

On the side of the guerrillas, the first US submarine that had brought weapons and other materials for them landed at Libertad – then part of the town of Pandan in the province of Antique – on April 30, 1943. On August 19, they received a second delivery of weapons, ammunition, communication equipment, generators, and fuel. The third supply of weapons and ammunition came on February 5, 1944, and on March 21, the fourth batch of supplies arrived. At that time, probably because of news of the massacre of the Americans at Tapaz, the submarine carried back 56 remaining Americans to Australia. By April, there were already more than 10 wireless radio bases established on Panay Island. Each landing brought from 20 to 200 tons of weapons, ammunition, medicines and other equipment; as a result, there was vast improvement in the equipment of the guerrilla forces throughout this period.

Through fragments of information on movements of the Japanese Army around us, we guessed that the war situation had worsened a little. We had been busy with one punitive expedition after another. However, that we were unable to grasp the larger reality from the details. The purpose of the construction of a large airfield in Negros was to render damage on the now counter-attacking US forces. Similarly, the construction of two other airfields – at Cabatuan in Iloilo and at San Jose in Antique – also progressed rapidly. The training unit of the Army Air Force led by Major General Anzai arrived in Iloilo, establishing its headquarters at the former premises of the JMA branch.

All these caused an increase in the comings-and-goings of aircraft at the Mandurriao airfield that made us sensitive to the tightening of the war situation. Hundreds of local people were forced to work at the airfield construction sites. With absolutely no machineries available, all work was done by manual labor with the use of shovels, picks and straw baskets. With the cooperation of both the Governor and the City Mayor, the Japanese Army assembled many people every day. Workers received Saigon rice as wages. The Japanese Army war currency was useless since counterfeits by the Americans had arrived.

There was no local industry at all in wartime Panay. Except for peasants, the young men of Panay had no choice to support themselves but to be a guerrilla or to be a mercenary of the Japanese Army. After the Philippines became independent with Japanese support, the policy was to adopt mercenaries from among Philippine POWs and others detained by the Japanese Army.

The Japanese Army called them the —— (hired men); on the other hand, the guerrillas referred to them as the Civil Defense Corps (CDC). Heeding their wishes, 300 were adopted; and, after a one-month training, they were attached to each Japanese company. While the Japanese Army was winning, they obeyed orders; but as soon as the guerrillas became active, they started to tip sides. Inside information of the garrison was made known to the guerrillas. Eventually, a lot of these —— escaped with weaponry or switched sides to be guerrillas. Thus, the mercenaries had disappeared.

Among the numerous cases of damage from mercenaries, the major one fell on the Sentry Squad led by Corporal Matsuoka of the Yoshioka unit in Antique province. They were on Trappist hill, about 120 meters high, looking down on the road between San Jose and Sibalom. Guerrillas also considered this an important point and had often attacked from there. In March 1944, Mosendo and Tickiman were assigned to the squad as mercenaries. One day at around 4 p.m., the two Filipino mercenaries offered everyone tuba; and, as the Japanese soldiers were drunkenly asleep, the two killed the Japanese with their rifles. With a signal of three shots, the guerrillas entered. They grabbed clothes, weapons, bullets and set the place afire. One of the Japanese soldiers happened to have gone outside to urinate. It was his report that revealed the annihilation of this squad.

At the sentry post of the 3rd Company at Barotac Nuevo in mid-June, there was also a betrayal by a hired soldier that resulted in the poisoning of a Japanese soldier and the death of 14 others. Corporal Ito was also killed while at his sentry post at Banate.

Riots among mercenaries often happened in each company. They were dangerous groups that were difficult to handle.

Most members of the Filipino constabulary established by the JMA were POWs of battles on the Bataan peninsula (almost all came from Luzon). Their garrisons were set up at the various points outside of towns and cities. However, many of them also changed sides. Some joined the guerrillas, some worked as their spies, and others simply escaped. Soon, their numbers, from the initial 200 recruits, were reduced to half, with most of them in league with the guerrillas. Hence, they could not be trusted. They often loitered around towns and the city and were dangerous and difficult to live with.

6.3 Another Joint Punitive Expedition

Until March 1944, it had been peaceful. Eventually, the guerrillas reorganized themselves and became active once again. They first attacked the Philippine railway trains and buses on the trunk roads. In due course, 1st Lieutenant Toyota’s garrison at Sara, which was situated farthest from the town, had to withdraw because of worsening conditions in the surrounding areas.

In the beginning, the surrendered Deputy Governor from Sara, Jose Aldeguer, cooperated with the Japanese Army but eventually stopped showing up. Other garrisons reported frequent attacks by guerrillas. Since I was in charge of ordnance (armament), one day I received several cartridges from the garrison at Tigbauan. I had never seen such cartridges before in Panay. The diameter was about the same as that of a 38-caliber pistol, but the length was double the size of those bullets. I was told that in spite of the light sound of their shots, they were fired from rifles in rapid succession. Reports on light shooting sounds came in continuously. Eventually, we learned of the new US model of carbines with 20-round cartridges developed for fighting in the jungle. There were also reports of the capture of these rifles. However, as it was against army rules to deliver any confiscated weapons of the enemy to unit headquarters, no one had turned in the captured guns. The carbine was convenient; with a range of around 400 meters and weighing one-third of the Japanese rifle, it was the best rifle for jungle combat.

Due to the increasing reports of guerrilla attacks, headquarters decided to send two companies of the Tozuka unit on an expedition around Mt. Dila-Dila near Calinog and Mt. Baloy where the alleged headquarters of the 61st Division was. By the beginning of April 1944, this ended without particular results as the guerrillas were able to escape. The village in the hills west of Lambunao was torched upon the completion of the operations.

Around this time, there was a massive reorganization of Visayas area units. The 16th Division was transferred to Leyte in mid-April. Lieutenant General Shiro Makino, the commander of this division, became the overall army commander in the Visayas. Soon after, the brigade headquarters gave the order for the Joint Punitive Expedition by army units in Panay and Negros. The goal was to destroy the wireless bases of the guerrillas–there were more than ten in Panay and several in Negros–and to obtain the wireless units.

This was a firm request of the Japanese Navy so that the Combined Fleet could use the Guimaras Strait as their base. They wanted the obliteration of the enemy wireless units to end the detailed reports of their movements to the US. (As I learned after the war, this was part of Operation Sho-go or the Victory Operation of the Combined Fleet. The channel between Panay and Guimaras was one of the front bases of the 1 st Striking Force of the Kurita Fleet.)

The Navy cooperated with the Army by transporting the 16th Independent Infantry Battalion (commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Shigeru Nishimura) from Bohol Island to lloilo by cruiser. The operation area of our unit was western Iloilo and Antique, the Nishimura unit was in eastern lloilo, and the Tanabe unit was in eastern Capiz.

Major General Takeshi Kôno set up the expedition headquarters at Iloilo City. The expedition took around 60 days, from early May towards the end of June 1944. The special punitive expedition company was organized within the Tozuka unit with 1st Lieutenant Fujii as company commander. I was the unit’s deputy commander and was in charge of intelligence.

The first mission was to seize the wireless radio of the 61st Division guerrilla headquarters at Mt. Dila-Dila and Mt. Baloy. During a fierce battle with a group of the guerrillas, their headquarters must have fled towards the direction of Antique. Near Mt. Baloy, we captured the children of a guerrilla officer: a bright girl who held a three-year-old boy in her arms, and three or four other younger brothers squatting at her feet. After an enormous effort to alternately soothe and threaten the girl, she finally told me that her father was Major Eriberto Castillon, the former head of the Civil Affairs Unit of the 6th Military District.

We also located an abandoned US-made wireless unit that measured 70 cm X 40 cm and weighed 12 kilograms. For three nights and four days we hunted for this small and light-weight radio, putting our lives in danger and undergoing many adversities. With our unit commander, we were all amazed at our luck in finding the portable radio and just kept staring at it. It must have been so easy to land many of such wireless units from a US submarine. It struck us silly that it had taken all three battalions to drag around for the capture of just one of these.

During the expedition, we were also astonished to find a specially printed US propaganda magazine – entitled Free Philippines – in a remote mountain village. On its cover was a portrait of MacArthur with the Stars and Stripes and the words “I Shall Return.” There was also the latest issue of Life Magazine. Among the photos in those magazines was one from New Guinea, in which many Japanese soldier corpses were lying on the beach while MacArthur, with a corncob pipe in his mouth, inspected the battlefields. There were photos of enormous tanks and aircraft as well as those that showed how the different the uniforms and equipment of US soldiers had become from those used in the battles in Bataan. It made us doubt our capacity to win against the US forces with their vast and excellent weaponry. We knew that the US forces were sending in by submarine propaganda materials and ammunition, not to speak of large numbers of radios. We also became wary of the intelligence capabilities of our headquarters. Given these realities, we wondered if the Navy and Army headquarters had been serious in ordering the capture of the wireless radios.

We climbed down the mountains with Nicky, the youngest Castillon boy, carried on the shoulder of a medical sergeant Nakamura. I left all the children with Governor Caram at lloilo City. The older sister Thelma and her father, Major Castillon himself, kindly wrote petition letters while I was imprisoned at Sugamo.

6.4 Attacks on the Submarine Supply Base

Towards the end of May 1944, the Japanese Army carried out a second mission to attack the US submarine supply base on the coastline in Antique Province. Guerrillas trapped the Japanese forces on the coastal road near Culasi. They had used up their bullets in the battles, but the ship (the Shinshu Maru) that came to pick them up was sunk by a US submarine. That had been the first voyage of the ship built at Iloilo City by the Shimamoto Ship Building Company.

While on this mission, we learned about the wireless radio base at Mt. Nacron in Aklan from which the Panay guerrillas were in contact with General MacArthur.