7.1 Air raids and the landing of US forces at Leyte

In March 1944, the Imphal Operation (Indian territory invasion operation) started. In addition, by April, the Japanese Army’s 16th Division headquarters advanced from Luzon to the island of Leyte.

Early in June 1944, the Allied Forces in Europe landed at Normandy. On June 19, the Battle of the Marianas was fought. In July 7, the Japanese Army on Saipan Island was annihilated. The shade of defeat had come to color those days. Of course, in Panay we could just guess at the whole war situation from the urgent movements of the Japanese forces around us.

In July 1944, the set-up of the Japanese Army in the Visayas Area was strengthened in preparation for the expected attacks of US forces. On July 26, the 14th Area Army (Homen Gun) established a new unit, the 35th Army, with its headquarters in Cebu City. It was placed under the command of Lieutenant General Munesaku Suzuki, with Yoshiharu Tomochika as the Chief of Staff.

The 37th Independent Mixed Brigade was reorganized into the 102nd Division with its headquarters in Iloilo City. Under this Division, the new 77th and 78th Brigades were organized, respectively commanded by Lieutenant General Kono and Major General Manjome. The commander of the 102nd Division was Lieutenant General Shimpei Fukue, commander of logistics under Lieutenant General Yamashita in the Singapore invasion. Lieutenant Colonel Hidemi Watanabe became the staff officer in charge of Division operations. The promotion to Major of Captain Kengo Watanabe and his assignment as Senior Adjutant officer of the 77th Brigade was through the recommendation of Colonel Hidemi Watanabe.

In May 1945, in a battle with US forces east of the town of Silay on Negros Island, a mortar shell hit and killed Major Kengo Watanabe. He was a leading man of merit in the war of Panay and died a glorious death as a Japanese soldier. Nevertheless, his notoriety as ‘Captain Watanabe’ is still remembered there. Mr. Osamu Yokoi of Oita Prefecture wrote, ‘I attended the burial of Senior Adjutant Watanabe. We dressed him in a new uniform, laid his sword on his chest, and a bottle of his favorite whisky beside him. After cutting his hair and little finger to be sent to his family, we buried him, praying that his soul will sleep in peace. Tears came into my eyes.’

With the reorganization in July 1944, a labor unit (sagyo tal) of 50 men led by 1st Lieutenant Michio Saitô was attached to Lieutenant Colonel Tozuka’s 170th Independent Infantry Battalion. I succeeded Captain Jiro Motoki as Adjutant of the battalion upon his assignment as Junior Adjutant Officer of the Division headquarters.

By the end of July, the Division headquarters was set up at the Iloilo High School. Henceforth, the headquarters of the Tozuka garrison unit moved to Iloilo City Hall. With the establishment of the Division headquarters, various elements – such as communication, artillery, transport, engineer, and so forth – advanced into the city, which then began to see crowds of Japanese soldiers. Nevertheless, the equipment of each unit was extremely poor. For example, the artillery unit only had US 75 mm field guns captured in Bataan, the engineer battalion did not have enough shovels, and the transport battalion had no horses – not even those of low quality – not to speak of any trucks. Soon after, these units would become part of the final battle at Leyte.

After the transfer of Division headquarters, Colonel Satoshi Wada, the Chief of Staff of the 102nd Division, ordered the formulation of the Iloilo City Defense Plan – along with the construction of air raid shelters and the Division defense position at Cordova (in Tigbauan, Iloilo) – in anticipation of the US forces’ attack on Panay. We made several concrete air raid shelters for the Division Commander and general staff as well as for Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka and officers of the unit headquarters.

In the meantime, the guerrillas had been supplied with mortars, rocket launchers, rifles, carbines and so forth, that made their equipment far more superior to that of the Japanese Army. They had become a handsome proper army of the Philippines.

The guerrillas started to attack during the day. Their bullets even reached the quarters of Division Commander Fukue near the Iloilo High School. Daily reports from garrisons at different areas were showing that they were under attack by guerrilla forces with superior firearms. Clearly, the guerrilla resistance was by now operating at full scale. Consequently, Colonel Tozuka ordered the chief of the 3rd Company that was at the Tigbauan garrison to send 2nd Lieutenant Itsusuki’s platoon to Iloilo City to serve as the defense unit for headquarters. Its primary responsibility for now was to protect and defend the city against guerrilla attack.

Announcing that soldiers should become used to battles, staff officer Colonel Hidemi Watanabe ordered any newly-arrived units from Japan (i.e., transport, engineer and others) to defeat the guerrillas. Some of them had fought in combat and expeditions in China. But when they were met by a guerrilla ambush, they were astonished by the overwhelming superiority of enemy firearms that were in no way comparable to those of the bandits in China. Unable to put together any counterattack, all they could do was to lie on the ground and finally ran back after many soldiers among them had been killed.

Each time a new unit arrived, staff officer Watanabe dispatched them on punitive expeditions so that they could gain experience. This caused a large number of casualties, but he gave them no consideration at all. The commander of the unit that suffered most requested for help from the heavy weapons forces of our unit. He led counterattacks against guerrillas in retaliation for the death of his subordinates. Eventually, his group grew to be a capable combat force.

On September 15, US forces landed on the island of Peleliu. It was around this time that the US air attacks began on the Philippines, with Davao receiving daily air bombings. US submarines also begun to be active; they sank and damaged Japanese transport ships, causing a halt in the sea traffic across the Philippine Islands. Continuous bombings took place at Cebu City on September 12 as well as on the northern part of Negros Island on the 13th. Moreover, on the morning of September 14, about 50 to 60 Grumman planes raided Iloilo City.

The enemy planes rained bombs on the Mandurriao airfield and the Iloilo Port. The southern part of the city was bombed as well. The Japanese had no anti-aircraft guns, and no friendly planes flew to challenge the carrier planes before they left.

In time, the city became quiet again; but several Japanese planes were destroyed and several ships were sunk at the harbor. Civilian houses were damaged, and a number of people were killed or injured.

Many residents left the city in terror. I visited the house where Major Castillon’s daughter Thelma and her brothers were, but they had already gone. More and more people kept leaving the city, drastically lessening the numbers of those who remained. One day a young Filipino brought me a letter from Thelma Castillon. In a scribble, she wrote, ‘I’ll never forget the kindness I received from you and the unit commander.’ Colonel Tozuka was glad too, saying, ‘She was a nice girl. I’m very happy to know they are safe.’

After the war, in the petition letter she wrote with her father for my release from Sugamo Prison, she said, ‘Had I not been helped by you, I would not be able to enjoy this happy life I have now.’ With words of thanks, she told me about her reunion with her parents and that after the war, she had graduated from university and was working for the Department of Labor. Her brothers were attending colleges of medicine and dentistry, and high school.

On October 16, to the musical accompaniment of the Warship March, the Imperial General Headquarters announced over the radio that the sea battle off Taiwan was the greatest Japanese victory since the attack on the Pearl Harbor. I felt the release of frustrations caused by US aircraft flying over us, dominating everything with their absolute power. The news commentator went on to say that the US advance to the Philippines had thus suffered a setback. That made us all feel greatly relieved.

Staff officer Hidemi Watanabe ordered the circulation of this news to the Filipino people as well and posted announcements on walls in various parts of the city, although no one was there to read them. Nonetheless, few days later, planes from the US Task Force flew southward from the sea off Taiwan and again attacked various airfields in the Philippines. This threw us into a state of disarray. The Division staff was also confused. As if urged on by the air raids, the guerrillas who had surrounded Iloilo City began to openly attack with mortars. While fighting with the guerrillas everyday, we also had to prepare for the US landing. The routes connecting our garrisons were under guerrilla control and we were just able to hold on to points still under our control.

In the midst of worsening war conditions, around October 7, we received a telegram that said, ‘General Yamashita, the Supreme Commander of the Area Army in the Philippines, takes direct command himself.’ General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the Tiger of Malaya, was the general considered the best commander in the battlefield, and we all felt encouraged. At the same time, we understood the dedication of the Japanese Army to the war in the Philippines.

On October 18, we received a report that the US fleet had bombarded the east coast of Leyte. On the 20th, a report came in: ‘US forces landed on Leyte. The 16th Division is counterattacking.’ We first heard some good news about the battle of Leyte. Then, there was a deafening silence.

7.2 Annihilation and Withdrawal of the Garrisons

Some troops were ordered to leave Panay to join the battle of Leyte where they perished.

Along with the US air raids of Iloilo City, the guerrillas were constantly attacking the garrisons in Panay. Among the Hôjin, women formed the Patriotic Association of Women. Twenty to thirty of them got together every day to make hand-made grenades from cut water pipes and dynamite.

In some garrisons, soldiers fought to the last man. In others, some were relieved and withdrew. Corpses of slain Japanese troops were left naked, beheaded, severed of their limbs or displayed in market places by the guerrillas. In many instances, there were too few soldiers at the garrison facing the enemy with superior firearms. Colonel Hidemi Watanabe did not seem to understand the new situation. Colonel Tozuka blindly followed his orders that caused those tragic cases of annihilation.

7.3 General Attack of Guerrillas on Iloilo City

In early November 1944, Hôjin males under 45 years old were conscripted by the order of Manila headquarters to form a unit. I started training the troops gathered in Iloilo.

We did not have information about the movements of the US forces; but by around December 12, we received an emergency telegram informing us that a great transport fleet was moving west through the Surigao Strait under guard of a powerful task force of the US Navy. If they were to land on Panay, it was expected to be at around dawn of December 14.

Since we were led to believe that the battle in Leyte was still going on, no preparations had yet been made in Panay. Guerrillas had completely cordoned off Iloilo City and any urgent troop movement was impossible. Toward dusk that day, information about the fleet movement stopped coming in. Colonel Tozuka, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I consulted and concluded that we should fight to the last man. Forces inside the city were ordered to get prepared. We could do nothing with only 2,000 aerial bombs. We all waited without sleep.

At around 2 p.m. on December 14, a kamikaze pilot made an emergency landing in Panay due to problems with his aircraft. He had seen the US fleet of several dozen ships going north along northwestern Panay. Given our forces at that time, if the enemy had landed on Panay, we had no other fate but to perish. On December 16, we heard on the radio from Japan that the US Forces had landed on Mindoro the previous day.

On Christmas Eve, the Lopez family invited Sergeant Matsuzaki and me. It must have been the worst Christmas for them. Knowing the obvious fate of the Japanese Army, I felt grateful for their kindness. On New Year’s Day of 1945, the Intendance Department gave one piece of rice cake (mochi) to everyone to celebrate the New Year. Actually, there was, no time to celebrate because of the guerrilla attacks. Around January 10, we learned from an American radio broadcast that US forces had landed at Lingayen Gulf in Luzon. The radio from Japan spoke of the good defense put up by the Japanese Army throughout Luzon, though their broadcast did not last long. We all felt worried and gloomy in the face of a rapidly deteriorating war situation.

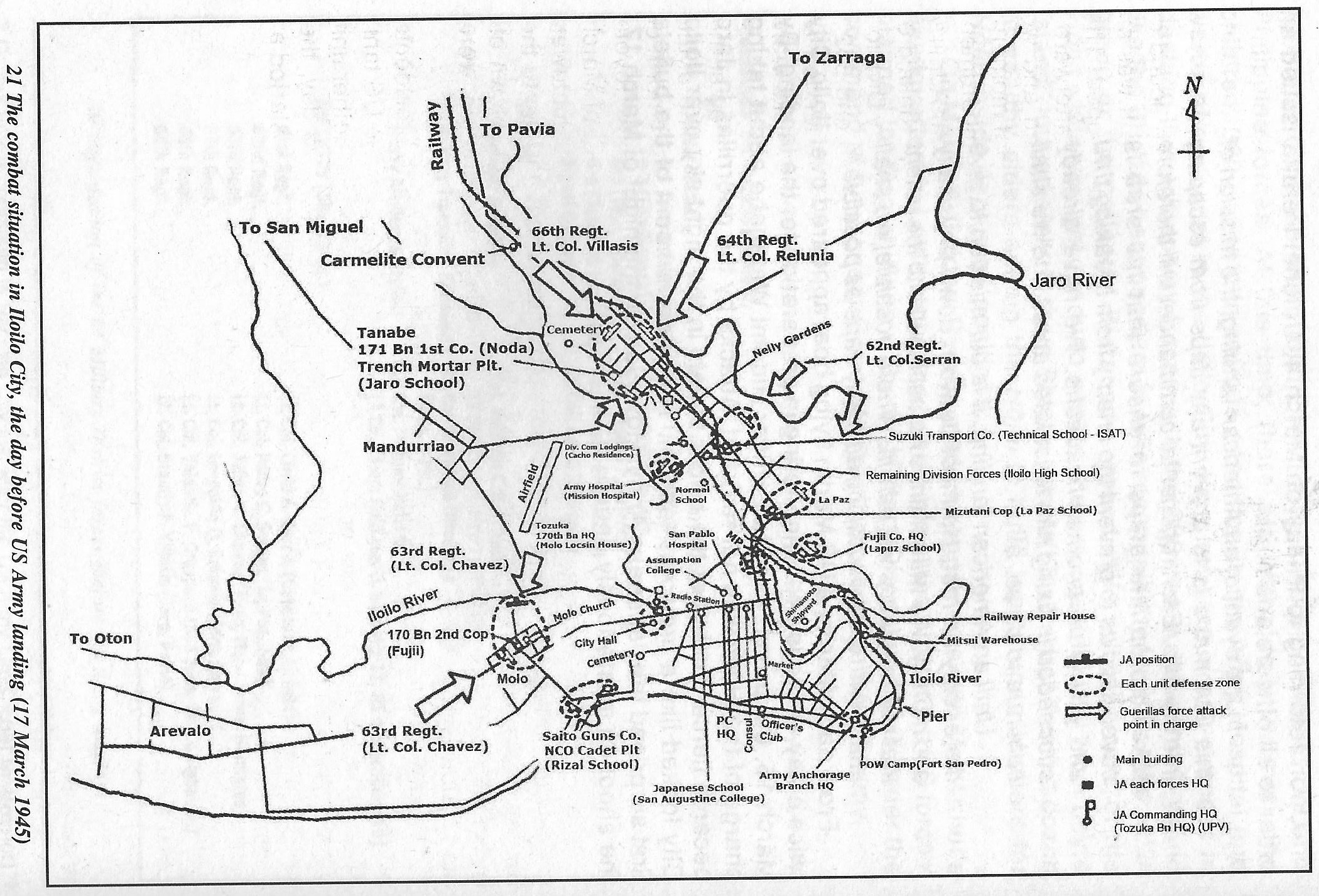

With their attack on the Cabatuan airfield on February 1, the guerrillas started fierce attacks on other different places. On February 9, they launched a general attack on Iloilo City. At that time, a number of US officers were in command of the fighting of the guerrillas as military advisers.

The attacks happened at Molo, followed by those at the northern part of the city, behind the Japanese Army Hospital in La The Noda Company of the Tanabe unit at the Jaro garrison became isolated in this siege.

We quickly decided to form three companies, consisting of the Saitô weapons unit, two squads of the communications unit, the Labor Platoon, the Cadet unit of NCOs, and the Suzuki Transport Company. Captain Saitô commanded and Lieutenant lshikawa joined as instructor.

Towards the evening, after a fierce battle, the guerrillas withdrew. The brave charge that the NCO cadet platoon made through the bullets surprised the guerrillas and local residents. I learned this from the Lopezes when Sergeant Matsuzaki and I were invited to see them a few days later.

The guerrilla attacks were fierce on our positions at Molo, Jaro and La Paz. However, after February 9, they gave up trying to regain control of Iloilo City by themselves, and decided to wait for the US landing. Nevertheless, the Japanese garrisons continued to come under ferocious attacks. US air bombings and bombardment by the guerrillas became more relentless throughout Iloilo City.

Gradually, residents were evacuating to other places away from the city. Mr. Fernando Lopez repeatedly asked the permission of Colonel Tozuka to leave Iloilo City through Sergeant Matsuzaki. Finally, Lopez personally came over to headquarters to ask. Still, the Commander did not approve. Eventually the family disappeared; I felt it was better because their presence no longer made a difference to the whole situation, and I prayed for their safety.

|

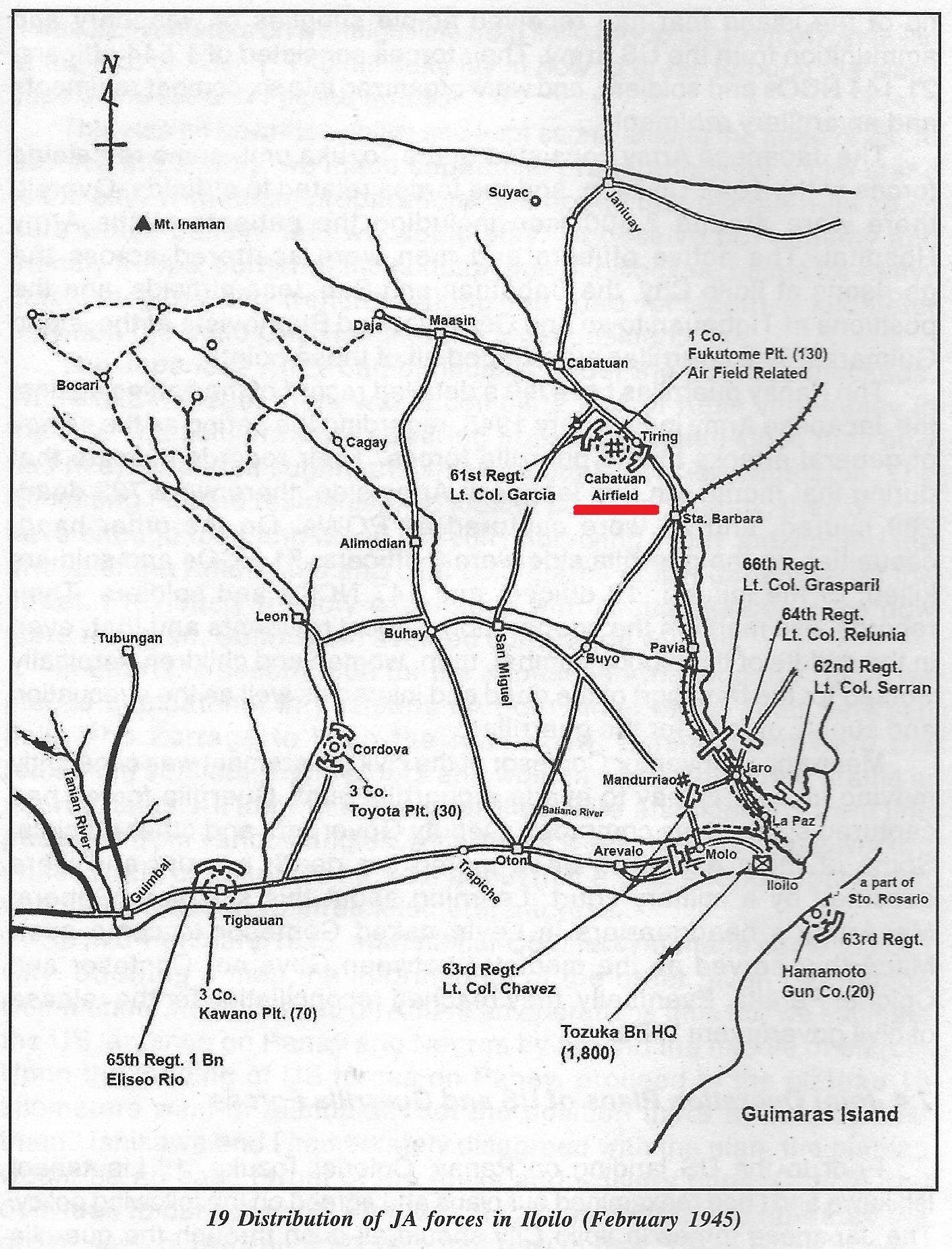

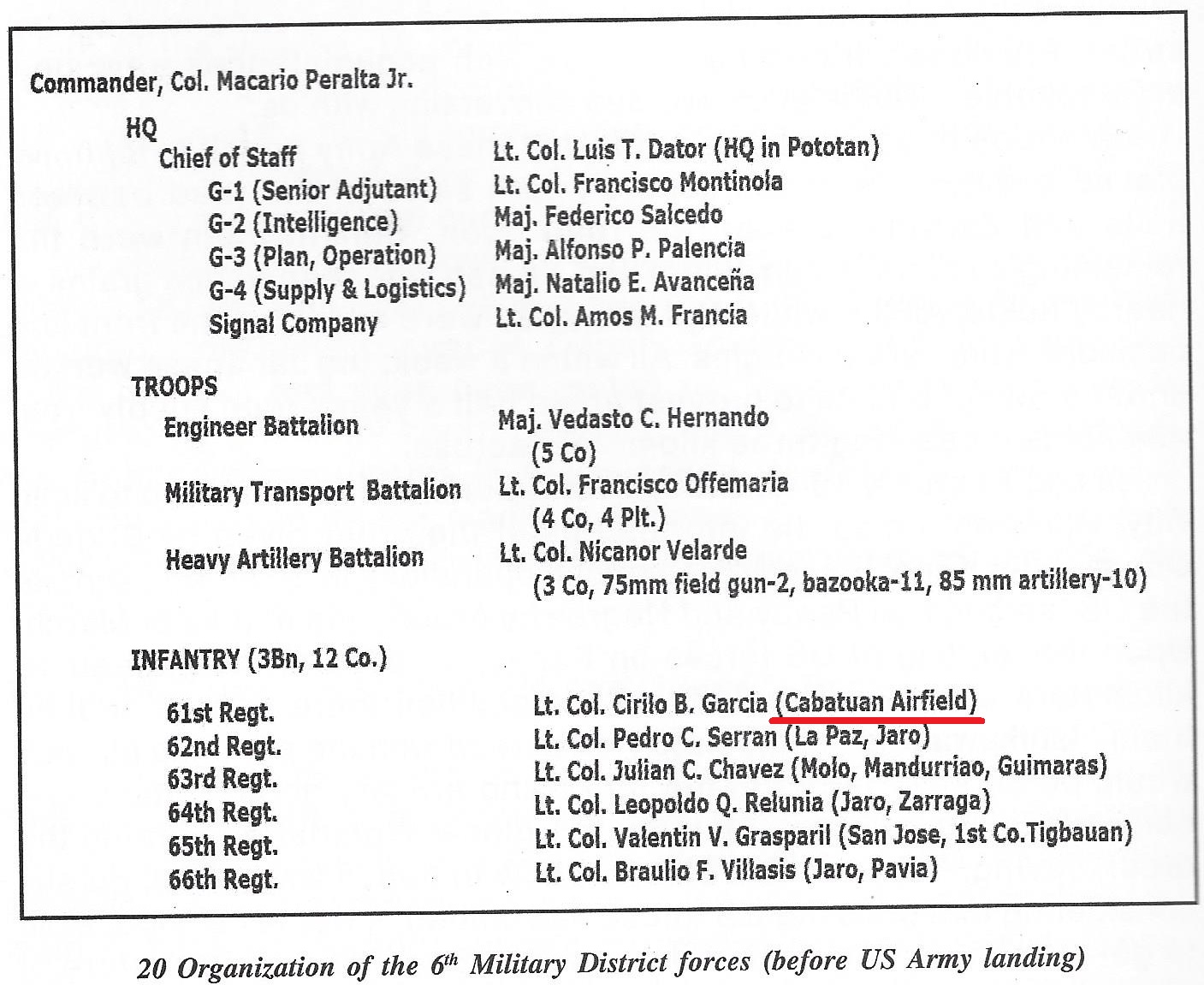

At this time, the guerrillas had moved the 6th Military District : headquarters to Pototan, 34 kilometers northeast of Iloilo City. They constructed an airfield in Dumarao in Capiz Province and completed repairs on the railway between Dumarao and Pototan. They also strengthened the facilities of the harbor at Estancia on the northeastern tip of the island that had received ample supplies of weaponry and ammunition from the US Army. Their forces consisted of 1,544 officers, 21,144 NCOs and soldiers, and were organized into six combat regiments and an artillery regiment.

The Japanese Army consisted of the Tozuka unit, some remaining forces of the 102nd Division, and the forces related to airfields. Overall, there were around 2,500 men including the patients at the Army Hospital. The active officers and men were scattered across the garrisons at Iloilo City, the Cabatuan and San Jose airfields, and the positions at Tigbauan town and Cordova, and Buenavista at the island of Guimaras. The guerrillas surrounded all of these points.

The Panay guerrillas have left a detailed record of the battles against the Japanese Army in February 1945, regarding the period as the climax of general attacks by the guerrilla forces. Their records indicate that during that month, on the Japanese Army side, there were 723 dead, 269 injured, and 24 were captured as POWs. On the other hand, casualties on the guerrilla side were 8 officers, 71 NCOs and soldiers killed; of the injured, 10 officers and 147 NCOs and soldiers. Their records also mention the cooperation of local residents and that, even in the middle of the bloody combat, men, women and children heroically worked for the transport of the dead and injured as well as the evacuation and supply of food for the guerrillas.

Meanwhile, Governor Confesor of the civil government was constantly moving all over Panay to evade a guerrilla hunt. Guerrilla forces had captured some of his comrades, Deputy Governors and other officials. Some of them had even been meted the death penalty and were executed by a military court. Learning about this situation, General MacArthur’s headquarters in Leyte asked Confesor to come over. MacArthur served as the mediator between Governor Confesor and Colonel Peralta. Eventually, they reached reconciliation for the release of civil government VIPs.

7.4 Joint Operation Plans of US and Guerrilla Forces

Prior to the US landing on Panay, Colonel Tozuka, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I had reexamined our plans and agreed on the following policy. The Japanese forces in Iloilo City should all dash through the guerrilla siege lines and go to the village of Bocari in Leon – situated south of Mt. Inaman, in the mountainous region in the west-central part of Panay Island – where they could continue fighting for as long as possible. Bocari, where Governor Confesor used to have his base, was an excellent haven in terms of both geographical strategy and food supply. The problem was distance. It was 22 kilometers on a straight line from Iloilo City to the town of Alimodian at the foot of Bocari. The difficulty lay in how to break through the siege lines of the US and Filipino armies.

This was an unwritten policy and kept secret among the three of us. To deceive the enemy, we made superficial preparations for a last stand in the city. With these preparations, we hoped that the guerrilla spies here would believe that we would stay. To deceive both enemy and friendly troops, I ordered the construction of pillboxes, bases for heavy machine guns and trenches along the road for about a kilometer between the Iloilo City Hall and the Molo position.

The Japanese Army had difficulties under the guerrilla blockade. While under siege, there was a complete lack of fresh vegetables in the city. The soldiers were suffering from malnutrition since they only had rice, unrefined sugar, and small amounts of dried vegetable. The remaining Filipino residents also looked pale. Apparently, they did not have enough food and faced difficulty surviving. They anticipated the arrival of the Americans and cast cold glares at any Japanese on the street. Previously friendly exchanges with acquaintances were now more reserved. Some even avoided conversing with us.

In efforts to secure food for the Japanese Army and the Hôjin, we placed combatants in positions on both sides of the road between Iloilo and Zarraga to keep the road open. Behind them were the remaining soldiers, Hôjin elders and women who reaped rice grains in nearby fields. All the while, the guerrillas were attacking the front line positions from various angles. All within a week, the Japanese worked under a rain of bullets to harvest about half a year’s food supply from rice fields measuring three kilometers across.

In mid-February 1945, staff officer Colonel Watanabe came to Iloilo City. Showing a map, he informed us of the order given by Brigade Commander Kono: ‘Based on American operations thus far, we estimate the US landings on Panay and Negros by around the middle of March. Upon the landing of US forces on Panay, proceed to the plateau 10 kilometers west of Alimodian, set the position there to fight against them.’ Ishikawa and I immediately disagreed with the plan; the plateau would be an easy target of the tanks and artillery guns. Critical and oblivious to our opinions, Lieutenant Colonel Watanabe repeated the order, saying, ‘All you think of is just how to flee.’ I was silent, quietly considering that once the US forces had landed, it would be impossible to get relief from brigade headquarters in Bacolod City. Therefore, it was unimportant whether we obeyed their order.

Eventually, I said, ‘We will follow your order. However, once the Americans land, it would be very difficult to rush through the 30-kilometer distance from Iloilo City through the blockade of US and Philippine forces. At this time, there are 250 elderly, women and children, 300 patients in serious condition in the Army Hospital and wards of each unit in the Iloilo City. I am not sure of any success in dashing through enemy forces with the 600 non-combatants. I would like the Brigade headquarters to take responsibility for either the Hôjin group or the patients.’ Watanabe replied, ‘We will take care of the Hôjin while you get ready to accept the seriously injured from Leyte Island.’ Immediately, Consul Shigeo lmai left for Negros with a dozen of healthy elders among the Hôjin to build the refugee shelters for Hôjin inside Japanese positions.

On March 1, Colonel Peralta made arrangements with MacArthur’s headquarters in Leyte regarding operations at the time of the US forces’ planned landing on Panay. The 6th Military District units fell under the command of Lieutenant General Eichelberger of the US 8th Army.

|

20. Organization of the 6th Military District forces (before US Army landing)

Commander, Col. Macario Peralta Jr.

HQ

Chief of Staff - Lt. Col. Luis T. Dator (HQ in Pototan)

G-1 (Senior Adjutant) - Lt. Col. Francisco Montinola

G-2 (Intelligence) - Maj. Federico Salcedo

G-3 (Plan, Operation) - Maj. Alfonso P. Palencia

G-4 (Supply & Logistics) - Maj. Natalio E. Avanceña

Signal Company - Lt. Col. Amos M. Francia

TROOPS

Engineer Battalion - Maj. Vedasto C. Hernando (5 Co)

Military Transport Battalion - Lt. Col. Francisco Offemaria (4 Co, 4 Plt.)

Heavy Artillery Battalion - Lt. Col. Nicanor Velarde (3 Co, 75mm field gun-2, bazooka-11, 85 mm artillery-10)

INFANTRY (3Bn, 12 Co.)

61st Regt. - Lt. Col. Cirilo B. Garcia (Cabatuan Airfield)

62nd Regt. - Lt. Col. Pedro C. Serran (La Paz, Jaro)

63rd Regt. - Lt. Col. Julian C. Chavez (Halo, Mandurriao, Guimaras)

64th Regt. - Lt. Col. Leopoldo Q. Relunia (Jaro, Zarraga)

65th Regt. - Lt. Col. Valentin V. Grasparil (San Jose, 1st Co.Tigbauan)

66th Regt. - Lt. Col. Braulia F. Villasis (Jaro, Pavia)

Upon returning to Panay on March 4, Colonel Peralta issued an order to all officers and men:

In the event of an American landing, the mission of this Command is to prevent any Japs from escaping into the hills. Each regimental commander will therefore take appropriate steps to ensure that his area is covered so as to prevent the enemy from breaking thru and giving us another headache. We have already succeeded in fixing him to isolated areas and we shall continue to do so.From early March, a US Martin flying boat appeared over Iloilo City twice a day, obviously reconnoitering in preparation for the landing. By March 15, the promise of staff officer Hidemi Watanabe about taking charge of the Hôjin was not realized. Attacks by the guerrillas in Jaro became fiercer such that the tracer bullets in the night sky over Iloilo City looked like a fireworks festival. The sheer amount of the bullets first surprised the Japanese Army. However, on the night of March 17, the shooting mysteriously ended.

Until an American landing, it is our mission to give the enemy no rest. He must be worn down physically and morally. We will continue harassing him to the extent that our resources will permit. Where possible, we shall attack with a view to killing as many Japs as possible.

|