8.1 US Forces Land on Panay

MARCH 18, 1945

Early in the morning of March 18, I was awakened by the sound of heavy explosions from the direction of the Tigbauan garrison. It was an emergency signal from the garrison but it suddenly stopped. The time was 4:50 a.m. The explosions lasted a few minutes and afterwards silence returned. We could not make contact with Tigbauan and we received no information from any of the other garrisons. At that moment, indeed, the garrison of the 3rd Company was blown off by bombardment from warships of the US Fleet and transport convoy led by Rear Admiral A.D. Struble, under the command of Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid of the US 7th Fleet. Around 7,000 men of the US Army’s 40th Infantry Division (185th Regimental Combat Team and 160th Infantry Regiment and 542nd Engineering Unit) headed by Maj. Gen. Rapp Brush had landed at Tigbauan. Around 200 vehicles such as tanks and military trucks were counted just along the road between Tigbauan and Cordova.

First Lieutenant Chiyomi Toyota of the 3rd Company stationed at the Cordova garrison was the only officer who witnessed the landing of the US forces. The Cordova position stood on a hill eight kilometers north of Tigbauan overlooking the Panay Gulf. With 30 other soldiers, Toyota had successfully parried guerrilla attacks. In the early morning of March 18, however, he awoke to terrible explosions and climbed the watchtower. He saw the blue-white lights of the warship bombardment and heard the blasts. Flashes from the Kawano unit’s position in Tigbauan, blown off by about 1,500 shells from bombardment of the landing warships, were also visible.

Eagerly waving little American and Filipino flags, the local residents excitedly welcomed the US forces in a festive atmosphere. The US tank forces attacked the Cordova position and Cabatuan airfield. Another unit entered Iloilo City to scout for other Japanese. On the same day, the construction of a temporary runway made of steel matting was started at Oton and was completed the next day.

|

|

Around 2 p.m., we suddenly heard guns in the direction of Molo – a dozen shots that moved from point to point, which made me wonder if the guerrillas had finally started using self-propelled guns. Running and stumbling like a rolling ball, an orderly from the Fujii unit soon arrived to report, ‘The enemy tanks are attacking the Molo position.’ The second orderly followed with the report, ‘A dozen enemy tanks are approaching and fiercely attacking from the direction of Molo. There are three or four tanks at the Molo Bridge. The landmines all ended up misfiring. Hurry up and send reinforcements!’ Damn, all my reliable landmines had misfired. I stomped my feet in frustration. Now there was no doubt about the landing of the US forces. First Lieutenant Ishikawa immediately sent the Machine-Gun Force and NCO Cadet Platoon to reinforce the Molo position.

Fortunately, by the time the reinforcements rushed to the scene, the enemy tanks had just withdrawn after rampaging around to their satisfaction. In this battle, First Lieutenant Sugahara fought against a tank at close quarters and was killed in action. A direct hit of the tank’s machine gun blasted off his upper body.

8.2 Fierce Fighting at Jaro: Breaking Out of the Siege

MARCH 18, 1945

The US landing was evident on that morning of March 18 and emergency calls were sent to the unit leaders.

MARCH 19, 1945

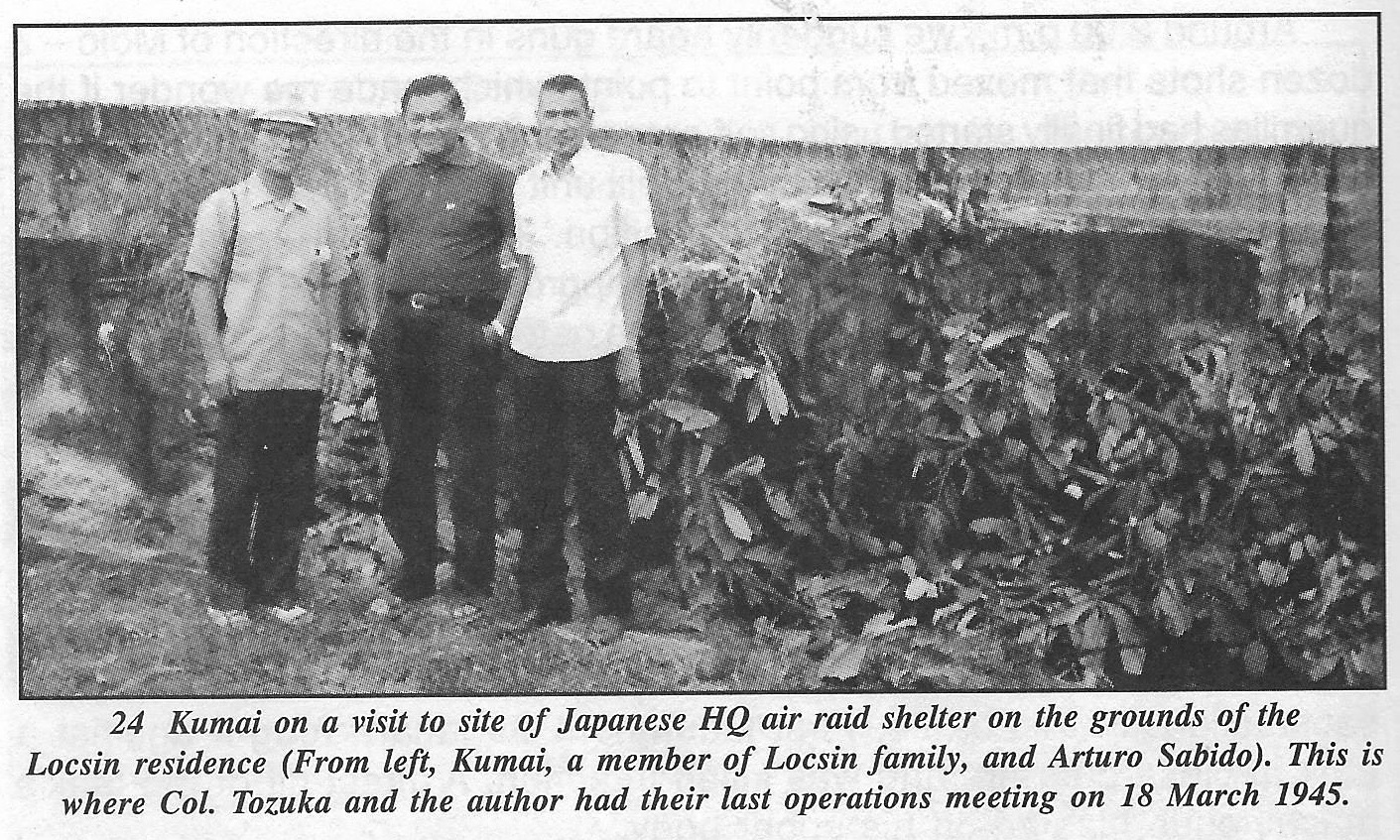

The Japanese Army in Panay had its final operations meeting at the headquarters’ air raid shelter at the Commander’s new quarters near the Iloilo City Hall in Molo. Previously the swimming pool at the garden of the Locsin family residence, the shelter was still in existence in 1973.

At the meeting, the headquarters staff all looked tense. Apart from Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka (unit commander). 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa, and myself, there were the following: Army Doctor Egami, Finance Officer 1st Lieutenant Kuge, 1st Lieutenant Yamamoto (deputy commander of the machine-gun force), Lieutenant Fujii of the 2nd Company, Captain Kaneyuki Koike (Kempeitai commander), and Lieutenant Noda of the 1st Company of the Tanabe unit, Commander Suzuki of the Transport Company, and 1st Lieutenant Mizutani (commander of the oil tank construction unit), a captain in charge of engineering of the airfield construction unit, Commander Ika of the Hôjin Company, 1st Lieutenant Nakamura of the remaining 102nd Division forces, President Kimura of the Japanese Association (Nihonjin-kai), and Medical Doctor Tanaka of the Iloilo Army Hospital. With a few dozen men, Captain Torao Saitô (machine gun unit commander) had left the previous night to lead the retreat of the Santo Rosario garrison at Guimaras. They managed to get back later that evening.

|

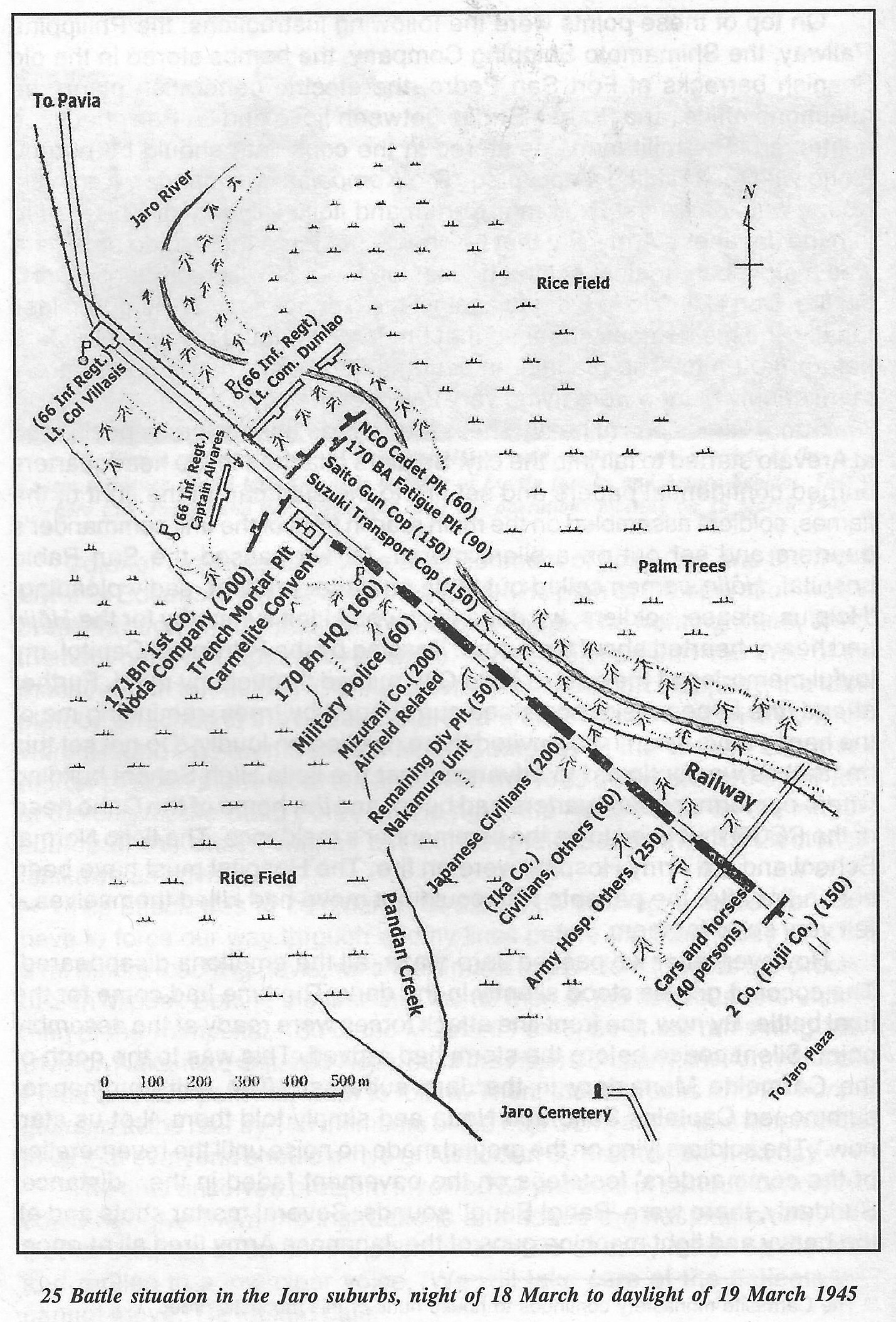

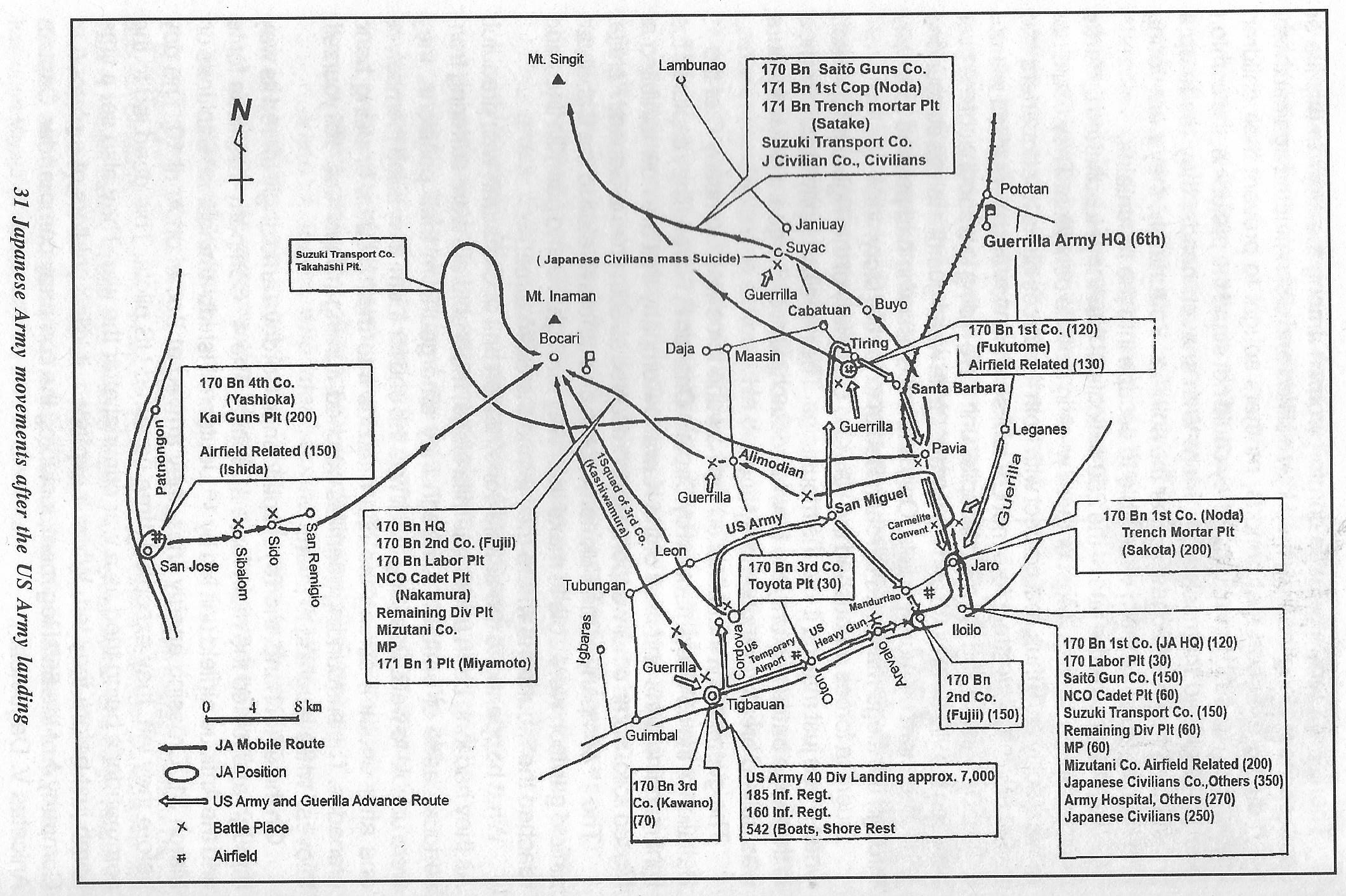

Colonel Tozuka ordered the abandonment of Iloilo City and the move towards Bocari. I then explained the plan. The plan of the operation was to break through enemy positions at Jaro by force. The front right line, under the command of Captain Torao Saitô, consisted of around 450 men of the machine-gun force, the NCO cadet force, the transport company, the labor platoon attached to the headquarters, and the communication unit. There were around 200 men from the Noda Company of the Tanabe unit and a mortar platoon at the front left line. With the road between Jaro and Pavia at the center, the Saitô Force on the right, the Noda Force on the left, the course of the attack was all left with Captain Saitô, with lst Lieutenant Ishikawa as adviser.

The attack was to commence at 8 p.m. that night, since we would have to force our way through enemy lines before the moon rose at 10 p.m. Before reaching Pavia, we should make a quick turn towards the direction of San Miguel. Behind the first line, the 60 men of the headquarters unit, 60 men of the Kempeitai, 180 of the Mizutani Force, 50 of the remaining 102nd Division Nakamura unit, 200 Hôjin, 80 of the Hôjin Company, the Army Hospital Force and 300 patients, were to follow. Then, the 20 trucks and 20 horses, guarded at the rear by 150 members of the Fujii Company. It was emphasized to all that everyone should arrive at Alimodian by dawn of the next day.

The final unsolved problem involved 50 patients in serious condition. I could not give them the instructions and asked the hospital chief, Army Doctor Tanaka, to do so. He seemed to have already made up his mind and replied in a low clear voice, ‘We will take care of the patients who cannot move.’ He looked pale.

On top of these points were the following instructions: the Philippine Railway, the Shimamoto Shipping Company, the bombs stored in the old Spanish barracks at Fort San Pedro, the electric generation plant, the telephone office, and Forbes Bridge between Iloilo and La Paz should be , destroyed. The military notes stored in the consulate should be burned along with the building it occupied. The Kempeitai commander, Kaneyuki Koike, was to request Governor Caram and Iloilo City Mayor Ybiernas to join the Japanese Army, but that he should not force them to do so. There was a strict ban against setting houses on fire and killing civilians. ‘Don’t ‘ set fire. Don’t kill. We’re fighting against the US, not against the guerrillas.’ Finally, the instructions stressed that the forces should assemble at Jaro before 8 p.m. The planning meeting adjourned around 5 p.m. By then, enemy planes were flying very low over the city.

Soon, explosions of heavy shells fired by the enemy forces positioned at Arevalo started to fall into the city. Soldiers attached to the headquarters burned confidential papers and set fire to the staff car.

In the light of the flames, soldiers assembled on the main road in front of the unit commander’s quarters and, set out on a silent march.

As we passed the San Pablo hospital, Hôjin women called out to us one after another, sadly pleading, ‘Help us, please, soldiers, we depend on you.’ I felt sympathy for the Hôjin and heavy-hearted about the future.

Passing by the Provincial Capitol, my joyful memories of the past in Iloilo City rushed through my mind. Further ahead, the Lopez residence stood surrounded by trees, reminding me of the happy days when I was invited there.

I yelled on loudly, ‘Do not set this on fire!’ as we continued to advance, past the Iloilo High School building where our former headquarters had been, and the home of the Cacho head of the PECO that used to be the commander’s residence.

The Iloilo Normal School and the Army Hospital were on fire. The Hospital must have been set on fire after the patients who could not move had killed themselves. I felt very sorry for them.

However, after we passed Jaro plaza, all the emotions disappeared. The coconut groves stood silently in the dark.

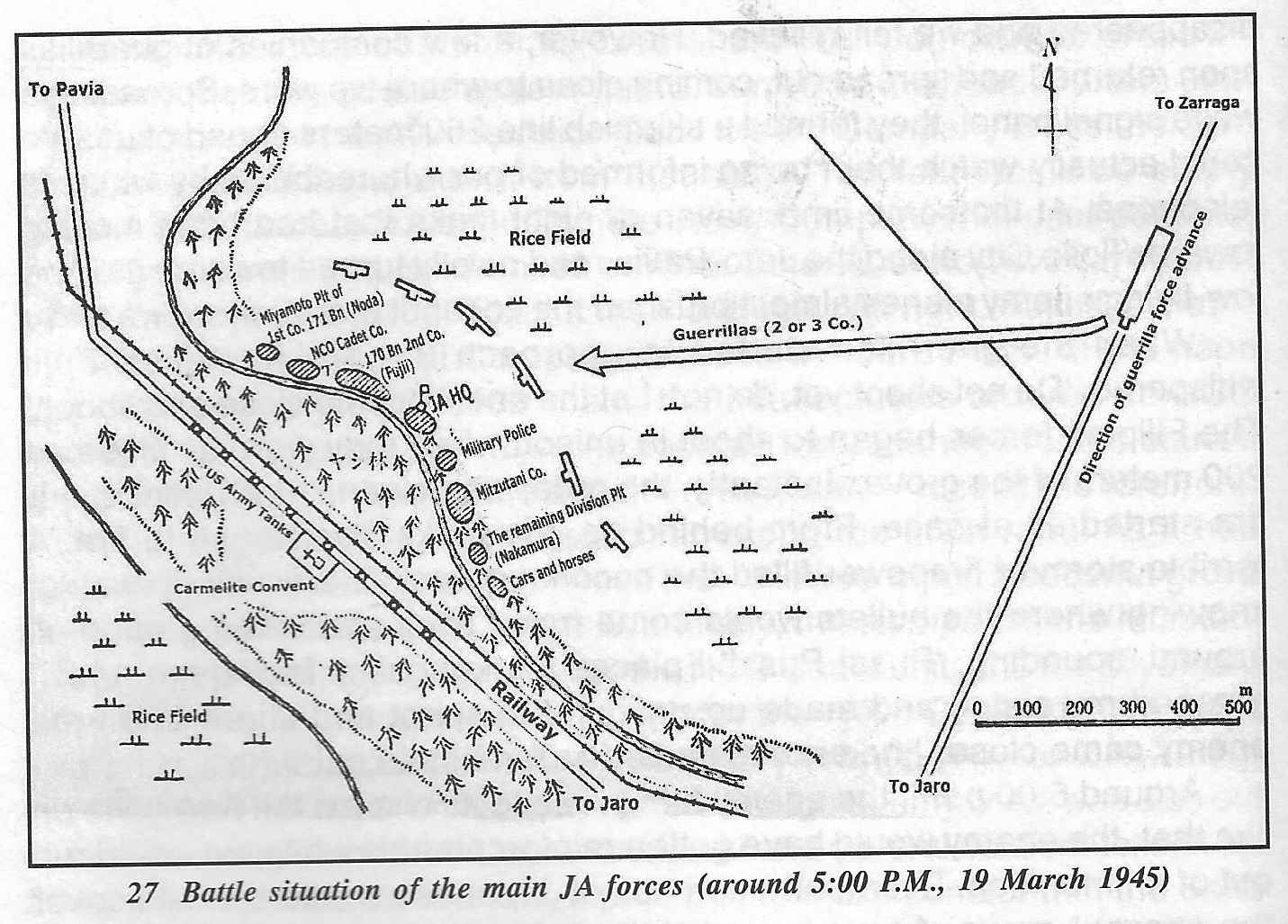

The time had come for the final battle. By now, the front line attack forces were ready at the assembly point. Silent peace before the storm had arrived. This was to the north of the Carmelite Monastery in the Jaro suburbs.

The unit commander summoned Captains Saitô and Noda and simply told them, ‘Let us start now.’ The soldiers lying on the ground made no noise until the reverberation of the commanders’ footsteps on the pavement faded in the distance.

Suddenly, there were ‘Bang! Bang!’ sounds. Several mortar shots and all the heavy and light machine guns of the Japanese Army fired all at once.

|

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: The above caption should be "night of 19 March to daylight of 20 March 1945" |

At the same time, just like strong winds and rains, torrents of enemy fire started. Especially distinct were thuds from 20 mm heavy pom-pom guns set on both sides of the road. The shells and bullets passed right above my head. After some time, the storm of shooting stopped and it became quiet. When the guerrillas noticed that we were moving, their volley started again. Afterward, silence returned. Two hours passed, yet there was no sign of a break through enemy lines. The moon was about to rise. It was now impossible to force through the blockade since we had about 400 elderly, women, children, and patients with us. There was also the danger of the US forces closing in from behind. Besides, we only had limited amounts of ammunition.

Whenever there was the slightest movement on the Japanese side, the enemy showered us with bullets. Eventually, news came that the front line commander Saitô was wounded. Colonel Tozuka and I were shocked, but immediately assigned 1st Lieutenant Yamamoto to replace him. Thus, March 18 passed* in this continuous exchange of firepower.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: *Kumai must have meant the end of daylight, or nightfall, of March 19, 1945. |

By dusk of March 19,* we ordered the front left forces of Noda to attack in the direction of the vast plain to Pavia. But before the command to attack could be made, there was a mighty guerrilla shooting spree that led to the bad news that company commander Noda, Master Sergeant Sô and other main officers of the company were killed in combat. Although Lieutenant Noda had dashed towards enemy positions, his subordinates were terrified by the fierce shooting and did not join him. Noda was shot to death as he was trapped in the enemy’s wire-fence. Master Sergeant Sô got seriously wounded and killed himself with his pistol.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: *This is the correct time and date, dusk of March 19, 1945. |

Since the main officers of the company were slain, the Noda force could not make the attack. I felt that a tragic end was rapidly falling upon us and was irritated that no good ideas were forthcoming. I only ordered all the vehicles to be burnt. Mortar fire continued. As I had sent a messenger to see how the Hôjins were doing, I heard that the women and children were getting bored and that some were making tea that the children wanted. They did not comprehend the mortal combat going on so close by, and I was concerned how they would react to this reality.

|

MARCH 20, 1945

At around 4 a.m. of March 19*, Lieutenant Fujii, commander of the 2nd Company that was posted as rear guard, surprised the headquarters staff by showing up suddenly. He said: ‘Shall the 2nd Company cross the Jaro River on the right and attack from that side? The rear would be empty without their protection, exposing the Hôjin Company, hospital patients, and Hôjin women and children left behind. Otherwise, however, we would all be destroyed.’ Colonel Tozuka then ordered, ‘All right, Fujii. Do that.’

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: *This should be 4 a.m. of March 20, 1945 (early morning the following day) |

Before long, the Fujii Company crossed the Jaro River. In the hope that other forces would follow them, the headquarters ordered an NCO liaison officer to guide the Hôjin. As soon as the Japanese forces started to cross the river, shouts of the attack – ‘Wah, wah’ – rose at the forefront. With those shouts, the whole group ran along the main road. As it had become light, we waited for the forces that followed within a coconut grove on the left bank of the Jaro River. Eventually, the Kempeitai, the Mizutani Force, the remaining Division forces, the NCO Cadet unit, and the Miyamato Platoon of Noda unit arrived – but without the Hôjin Company, the Hôjin women and children, and the Army Hospital patients.

The Saitô force, which had penetrated through enemy lines, was also out of contact. I dispatched 2nd Lieutenant Itsuki and several soldiers to look for those who were left behind and, if possible, to make contact with the Saitô Force. The headquarters’ group stayed in a dangerous zone three kilometers north of Jaro while waiting for the Hôjin. Soon, 2nd Lieutenant Itsuki returned running out of breath: ‘The enemy tanks are coming. When I was looking for the Hôjin and Army Hospital patients, I met the tanks and came back. At the height of the battle last night, dozens of Japanese and Filipino soldiers had fallen, lying on top of each other.’

On March 19,* the Japanese Army was still within enemy positions and in a worst-case situation. Soon, we saw enemy tanks moving on the Jaro-Pavia road, about 200 meters across the river from where we were in the coconut grove. Trucks full of soldiers followed the tanks. After this column, another series of tanks and trucks went towards Iloilo. Enemy planes were flying low in the skies above looking for Japanese soldiers. In due course, we heard a voice saying, ‘Enemy on this side as well.’ We then saw a great march of guerrillas heading for Iloilo City on the Jaro-Zarraga road, about 800 meters away from the grove. There were several US vehicles but others were on foot, and we could also see a large number of guerrillas moving. On our left were the American forces; on the right were the guerrillas. The Japanese Army was surrounded and could not move.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: *This should be March 20, 1945 |

The march of the enemy that began around 8 a.m. went on late into the afternoon. By this time, local residents had joined the guerrillas and there was no end to their procession. We all hid ourselves in the trenches that the guerrillas had dug. Earlier, around 4 p.m., the procession had disappeared and we felt relieved. However, a few companies of guerrillas soon returned and spread out, coming close to where we were. Spreading a white signal panel, they formed a skirmish line 250 meters ahead of us. We could actually watch them being informed of our whereabouts by wireless telephone. At the same time, seven or eight tanks that had been moving towards Iloilo City along the Jaro-Pavia road noisily turned towards us. The low-flying enemy planes almost brushed the coconut grove where we hid.

When the guerrillas started to approach us, 1st Lieutenant Fujii whispered, ‘Do not shoot yet, do not. Let the enemy come close and shoot.’ The Filipino forces began to shoot in unison when they were as close as 200 meters of the grove. Instantly, the order was given, ‘Fire!’ Hence, our fire started all at once. From behind us, the tanks also began to fire. A terrible storm of firepower filled the coconut grove. There was no way of knowing where the bullets would come from. They struck the ground all around, sounding, ‘Puss! Puss!’ I placed my knapsack facing the tanks, grasped my pistol, and made up my mind to shoot and shoot when the enemy came close. I had not expected to remain so calm.

Around 5 p.m., the enemy firing rose to its climax. If it had gone on like that, the enemy would have gotten reinforcements while we would run out of ammunition. Eventually, corpses of Japanese soldiers would cover the coconut grove. As we were fighting with our last burst of energy, a miracle happened. First, the shooting from the guerrillas decreased and, gradually, they retreated. At the same time, the tanks behind turned away – making ‘Guyee, guyee’ sounds – and left towards the direction of lloilo City. The darkness of night fell and the coconut grove regained its stillness. There was no moon. Two bullets dropped off my knapsack and two pairs of my socks inside the pack had holes in them. Candlelights silhouetted the figures of nuns at the Carmelite monastery beyond the river. They must have been having a mass to celebrate of the liberation of Iloilo City. One of the soldiers ground his teeth, saying, ‘Shit! I’ll attack you!’ I told him ‘Stop, Stop’ as I held him back.

Although everyone was tired, I advised the unit commander to make an advance. I felt that there was something ominous about the swift retreat of the enemy and that we should reach our destination as soon as possible. With the Fujii Force in front, we had been moving towards Pavia for seven or eight minutes when enemy artillery started shooting simultaneously at the coconut grove where we had been. The thuds – ‘Dahn, dahn’ – lasted for half an hour without interval. We had narrowly escaped by a hair’s breadth.

Using a compass as our guide, we crossed the Jaro River at about a kilometer south of Pavia and moved west. The US forces continuously launched flares that helped our movement in night’s darkness. However, we sometimes caught our feet in telephone wires laid out by the enemy.

|

The guerrilla forces that met us near the Carmelite monastery in Jaro on the 18th and 19th of March were those of the 66th Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel Braulio Villasis, which had most soldiers coming from Capiz. To our left, by the side of the convent, were members of the 2nd Battalion led by Captain Alejo Alvarez. To our right, on the other hand, was the 1st Battalion led by Major Pantaleon Dumlao.

8.3 ‘Advance by Turning’: Mass Suicide of the Hôjin

As enemy planes kept flying low by day, we hid in the jungle and vigorously marched toward the west at night, guided by the compass and the Southern Cross.

On March 20, while avoiding guerrilla soldiers and US forces whom we saw, we sought cover in the jungle three kilometers northwest of the town of San Miguel.

At daybreak of the 21st, we went swiftly through the town of Alimodian.

At the village of Cagay on the 22nd, we were fortunately able to make the prearranged contact with the Yoshioka Force from San Jose, Antique. We had sent them a radio message to abandon San Jose and move to Bocari.

Throughout the night of the 23rd, we marched briskly, even as a number of soldiers with us kept dropping. We could not do anything but to scold and encourage them to keep on walking. Some soldiers had been injured in the break through the enemy line and could no longer move on; quite a number of them took their own lives.

Thus the dawn of March 24 came. With the sound of the roaring river and the mountains soaring all around us, we came upon the village of Bocari that lay beneath. It was a fresh morning. I surveyed the topography from the mountain above and then counted around 600 houses in the village, with water in the valley, fields of rice and other crops, it was the ideal layout for a position. Presumably, the whole unit would have enough to eat for half a year. We decided to make this our base. The total number of the soldiers assembled was around 700.

SAITO FORCES

On the other hand, the Saitô forces, which had come to be separated from the main force, made a quick advance toward Pavia after engaging in a fierce combat.

MARCH 20, 1945

In the early morning of March 19,* they had crossed the Jaro River behind the town hall of Pavia. They reached a coconut grove about half a kilometer northeast of the town where they stayed to wait for the rest of the group. Under the command of Captain Saitô then were 150 men of the machine-gun force, 130 of the Suzuki transport company, 180 the Noda company of the Tanabe unit, 50 of the Ika Hôjin company, 30 of the remaining 102nd Division Force, and 200 Hôjin women and children. However, patients of the Army Hospital and some soldier dropouts were also left behind. Captain Saitô dispatched a messenger squad to inform headquarters of their whereabouts; but upon meeting with enemy tanks, the squad returned without making contact.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: *This should be March 20, 1945 |

Taking over command from the wounded Captain Saitô, 1st Lieutenant Yamamoto led the forces and the Hôjin.

They left the spot around noon, and by around 1 p.m., they reached a coconut grove about a kilometer and a half north of Pavia where they rested until it was dark. They started again at 8 p.m., passing three to four kilometers north of the town of Santa Barbara, and reached the heavily wooded area of Barrio Buyo, four kilometers east of the town of Cabatuan. They hid there the next day and resumed their movement at night. On the way, they frequently had to cross a road used by US military trucks.

Around 5 a.m. of March 21, they entered a mountainous area of Suyac of Barrio Tigbauan Road, part of Maasin, and about four and a half kilometers southwest of the town of Janiuay. It was in this forested mountainside with a river running below where they decided to take a rest until it was dark once more.

Using a straight line, the distance of Suyac from Pavia was only 25 kilometers. However, it seemed longer then since it was difficult and dangerous to move at night. The elderly Hôjin men, women and children were physically and mentally exhausted. In the beginning, they each had large packs on their backs full of necessities and carried other possessions in both hands. Some even had children with them. In time, they were tired and dragged themselves as they trailed after the soldiers’ lead. Some soldiers helped carry the children or their bags. Gradually, though, the bags were left behind. Since some soldiers were still tense from their skirmishes, they warned the Hôjin, ‘Do not let the children cry. Their sounds will tell the enemy where we are. What are the parents doing?’ ‘Kill the child!’ When children started crying, therefore, their mothers scolded them like mad. Some desperately covered the children’s mouths with their hands to suppress the noise. In this overwrought atmosphere, Kichisaburo Maruyama of the Iloilo Consulate strove to protect the Hôjin by mediating between them and the soldiers.

The net of the guerrilla siege was gradually closing in.

In addition, at around 5:00 p.m., the US artillery started a rigorous bombardment of the area from nearby Maasin. With the explosions, the assembled Japanese fell into disarray. The Hôjin, in particular, had lost whatever spirit and energy they had left.

Sometime later that night of the 21st, around 40 Hôjin got together. The principal of the Iloilo Japanese School Kayamori spoke out what was in his mind, ‘I feel that we should not be a further burden to the soldiers. Let us die here.’ Others thought it better to live even if humiliated. Nevertheless, they sang their farewell song in unison – Umi Yukaba (If I Go to Sea) – and bowed in the direction of the Imperial Palace. Some killed themselves with pistols and hand grenades. Failing to kill themselves, some mothers in agony sought the help of passing straggling and wounded soldiers who used bayonets or hand grenades.

Some of those soldiers finally caught up with the Saitô force and told the others of the mass suicide (jiketsu). The news spread among the soldiers and finally reached Captain Saitô. He was shocked; he ordered Corporal Katsuyoshi Yamaguchi of the headquarters wire communications unit and several other soldiers to confirm the news of the Hôjin suicides. Corporal Yamaguchi and others dared to go back through guerrilla lines and reached the place of the mass suicides at Suyac in the early morning of the 23rd. They found and identified the bodies of Principal Kayamori, who had a pistol shot on his right temple, and many corpses of those who had killed themselves. However, as guerrillas started to attack, they had to leave without being able to collect the remains.

28. Sketch of the mass suicide site (night of 21 March 1945) (based on interviews with local residents) |

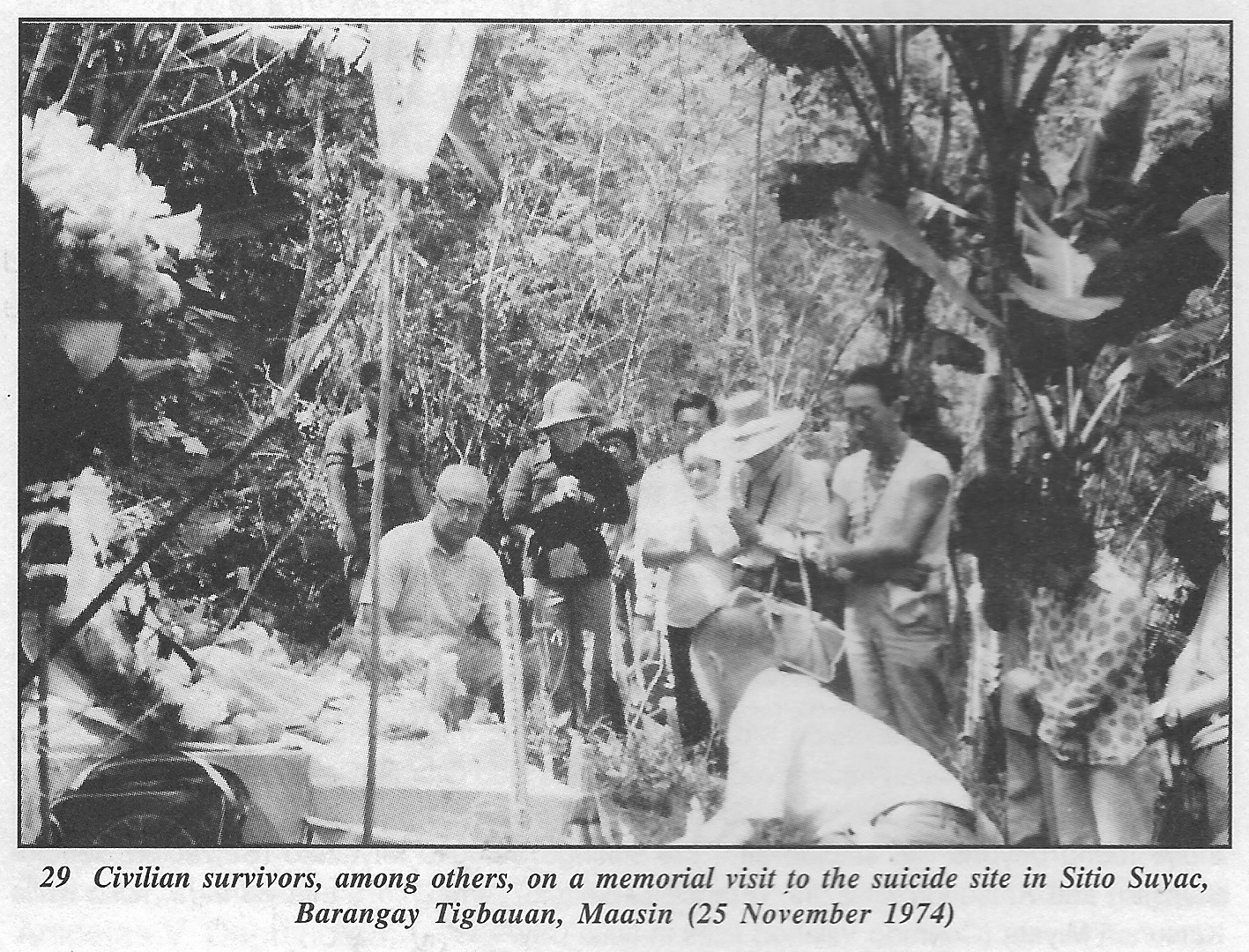

29. Civilian survivors, among others, on a memorial visit to the suicide site in Sitio Suyac, Barangay Tigbauan, Maasin (25 November 1974) |

Later research made it clear that around 40 elderly men, women and children perished here, although only 22 identities have been confirmed.

Appendix E - Partial List of Japanese Civilians in Mass Suicide

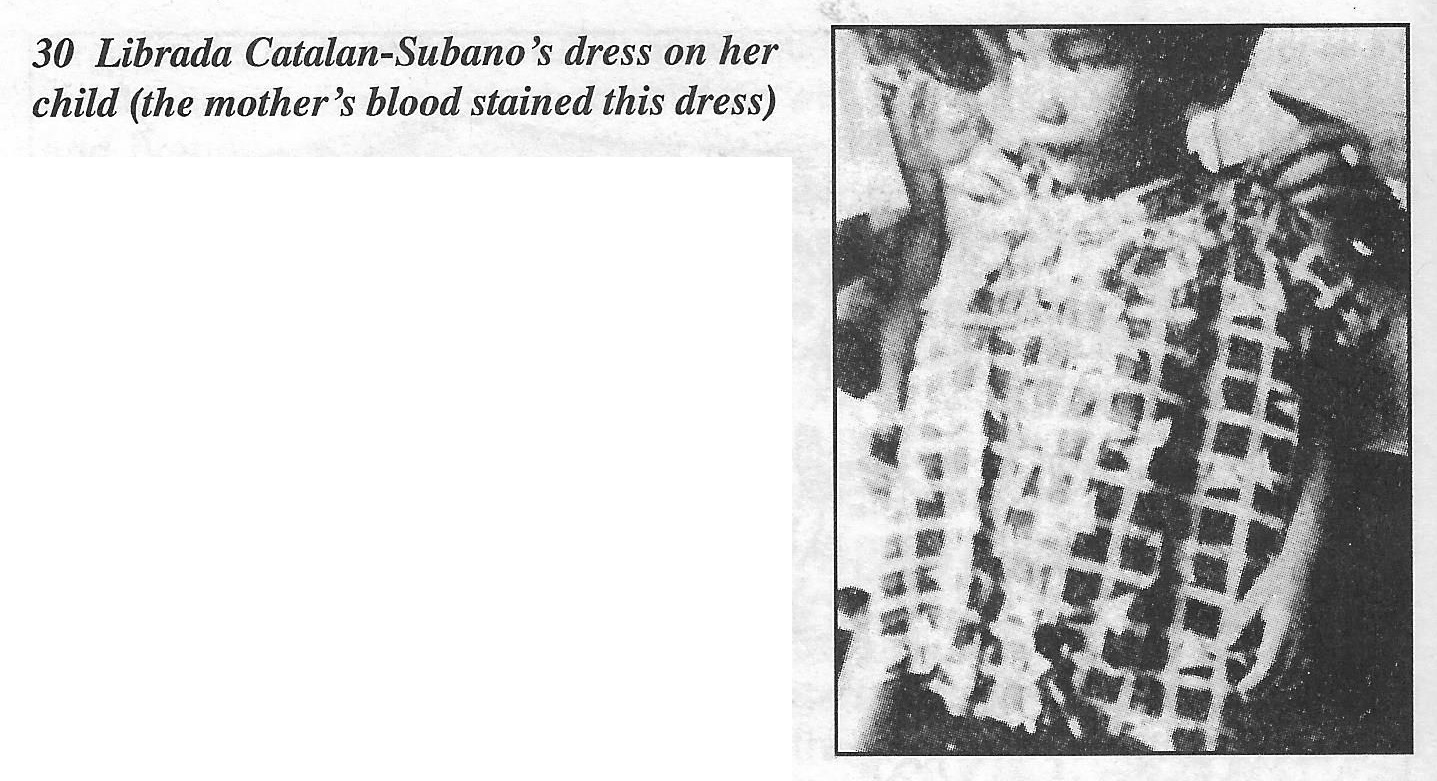

See also: Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano) in Cabatuan.

At the scene, guerrilla soldiers or local civilians rescued five Japanese children, four of whom now live in Iloilo.72 After the war, I looked for their parents and was able to establish the identity of two of the children: Salvador Cabrera and Salvacion Moreno, originally the Kawakami brother and sister, Tadanori and Mihoko. By then, however, their father Tokumatsu Kawakami in Kumamoto passed away in 1962.

At the time of his rescue, Salvador Cabrera had been in the first or second grade of the Japanese school. He described the situation as follows:

We were ordered to leave our school at San Agustin College to go to the mountains. I walked with Mother and other elderly people. Whenever we tried to rest along the way, soldiers ordered us to move faster and faster; so even when we felt awful, we walked on. The US forces started to shoot the area near us, so we all lay flat on the grass. Eventually, shells started to drop around us. The Principal of the school assembled Mother and others; they sang our National Anthem (Kimigayo), and he prayed. As shells fell around us, I ran away with my sister. We hid ourselves all night, and in the morning, when we returned to where Mother was, she and our younger brother were dead; other acquaintances were dead as well. Eventually , Ireneo Cabrera, who later became my stepfather, came and took me to his house. Vilda Moreno took my two sisters. (Another sister, Sumie, who also survived died young of disease.)

|

| 72 Mihoko Kawakami (Salvacion Moreno) now lives in the United States; Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano) has moved to Japan; and Isao Onaga (Salvador Maravillosa) now lives in Manila. Lazaro Tuban was reported missing as a crewmember of a cargo vessel. Of those found beyond the suicide site, the siblings Setsuko Miyazato (Salvacion Sequio-Solasito) and Kiyohiko Miyazato (Francisco Sequio) remain in Santa Barbara, Iloilo while Katsunori Miyata (Conrado Villaflor) lives in Iloilo City. |

|

Note from Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay:

Some Nisei children retrieved from the site that have been traced; parenthetically, they were given Spanish-sounding names by adoptive families evocative of having been resurrected or saved. The children of Tokamatsu Kawakami were raised by nearby families: Mihoko (‘Salvacion’) and Sumie (‘Gloria’) with the Morenos, and son Tadanori (‘Salvador’) with the Cabreras. Mihoko (5 years) and Tadanori (7 years) were old enough to remember that, fearful of the explosions and gunfire around them, they had fled from the group that night; upon returning when the guns were silent, they stepped over dead bodies to find their mother and younger brother among other acquaintances at the site. From beside a bloodied woman, a very young boy was picked up by locals and turned over to the care of parish priest who gave him his name; ‘Lazaro Tuban’, though deemed of Okinawan origin, his identify was never verified. Young Seizo Tôma, who grew up as Pablo Delgado in Negros, survived almost unscathed while his brother Diego sustained serious wounds. With stab wounds on her side, Chiyo Saki, awoke from a faint to see unwounded but crying children being taken away by Filipino soldiers, particularly the 3-year-old Isao Onaga. She had carried him throughout the retreat to help her friend Natsu Onaga who had her own hands full with a 4 year-old son besides a baby; the Onaga boy she carried grew up as ‘Salvador Maravillosa’ with a local adoptive family. With sharpnel wounds, Tami Oshiro regained consciousness to find that her parents had died along with 2 of the 4 children with them who were missing. The fate of her son was not ascertained; but unknown at that time, a guerrilla soldier who was among the first on the scene had carried away 3-year-old Toshiko Oshiro to his hometown of Cabatuan, where she was taken in by the Catalan family and named ‘Librada’. Kazuko Miyata (later Wakasa) was removed from the site where her mother and younger brother had died; she was brought by American troops with other wounded from Panay to a hospital in Cebu where she found her father with a bullet on his thigh from the escape from Iloilo City. Both recuperated and returned to Japan; but she still bears bayonet scars on her belly. - Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay Tracing the Roots of the Nikkeijin of Panay, Philippines |

See also: Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano) in Cabatuan.

There were ten Taiwanese comfort women among the Hôjin in this life or death escape. Along the way, the Hôjin disliked and discriminated against them. Even during the short rest periods, mothers sought to prevent their children from coming close to them. Since they could not stand the prejudice, the comfort women disguised themselves as men. With shaven heads, they made up a group of their own and chased after the soldiers. Fortunately, they were young and healthy so all of them were able to escape into the mountains.

More tragic was the fate of the 250 patients of the Army Hospital led by Army doctor Captain Tanaka. Most of them were in serious condition. They could not move quickly and, thus, lost contact with both the forces of the headquarters and that of Saito. These stragglers met US tanks on the way and were killed without a fight. Dr. Tanaka and the main Hospital unit were hiding in a sandbar of the river between the village of Buyo and the town of Pavia when guerrilla forces surrounded and killed them by mortar shells. Only a few medics who had pushed their way through the siege managed to reach Bocari to tell the story.

TIGBAUAN

Guerrilla forces ambushed the Kawano Company of the Tigbauan garrison when it was just making it into the mountains. The main company force perished in the fierce battle and only the forward detachment of Sergeant Kashiwamura was able to break through enemy lines.

The guerrilla unit that attacked the Kawano force was Company C of the 1st Battalion of the 65th Regiment led by Captain Orlando P. Flores. They captured the light machine guns and rifles of the Kawano Company that are now exhibited at Museo Iloilo. Some other weapons were presented as souvenirs to General Peralta.

CABATUAN AIRFIELD

The 1st company of the Fukutome force and others related to the Cabatuan airfield garrison were able to make their way through US and guerrilla lines and reached the mountains where they joined the Saitô force.

What happened to the airfield construction unit of Cabatuan was dreadful. As they had long been under guerrilla siege, most soldiers were suffering from serious cases of beriberi. Although they emerged from their positions, they were unable to walk. Realizing that it was the end for them, they killed themselves one after another, aiming the rifle muzzles into their mouths or using hand grenades. The surrounding guerrillas watched, cursing in Japanese, ‘Kill yourself, thieves,’ while laughing at them.

CORDOVA

On the other hand, the Toyota platoon at Cordova amazingly forced its way through and joined the main force at Bocari.

SAN JOSE, ANTIQUE

The 4th Company Yoshioka force and the Antique airfield unit led by 1st Lieutenant Ishida abandoned San Jose on March 31. Crossing enemy lines, they arrived at Bocari on April 10. The day before they left, they executed three captured US pilots. This deed led to the commander’s being tried as a war criminal after the war. They also set a time bomb just before they left. When it exploded, it killed soldiers of a platoon of Company A of the 6th Regiment, including the company commander, Captain Anicetas V. Daguinotan.

|