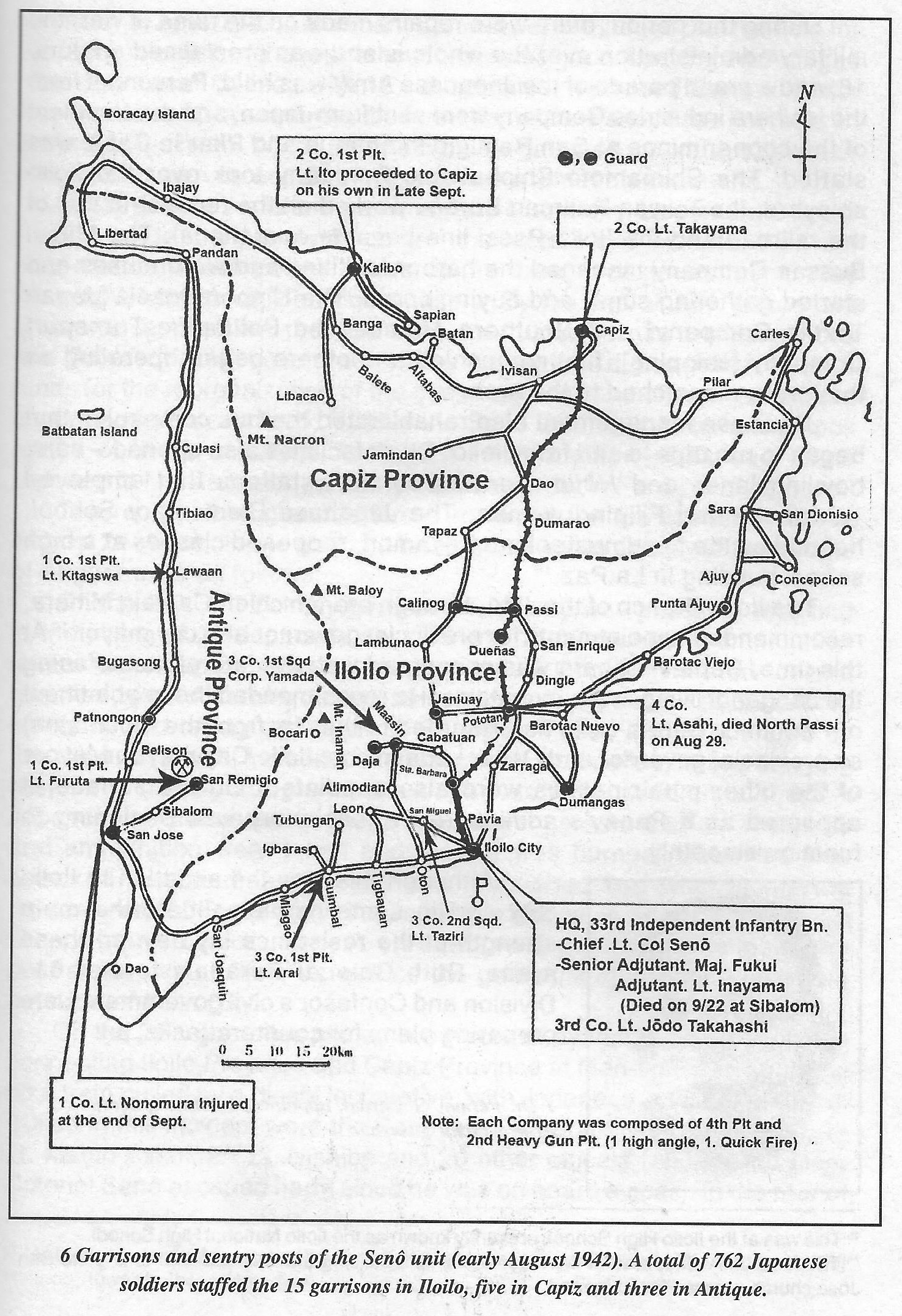

1.1 The Situation Gets Tense in Panay Island

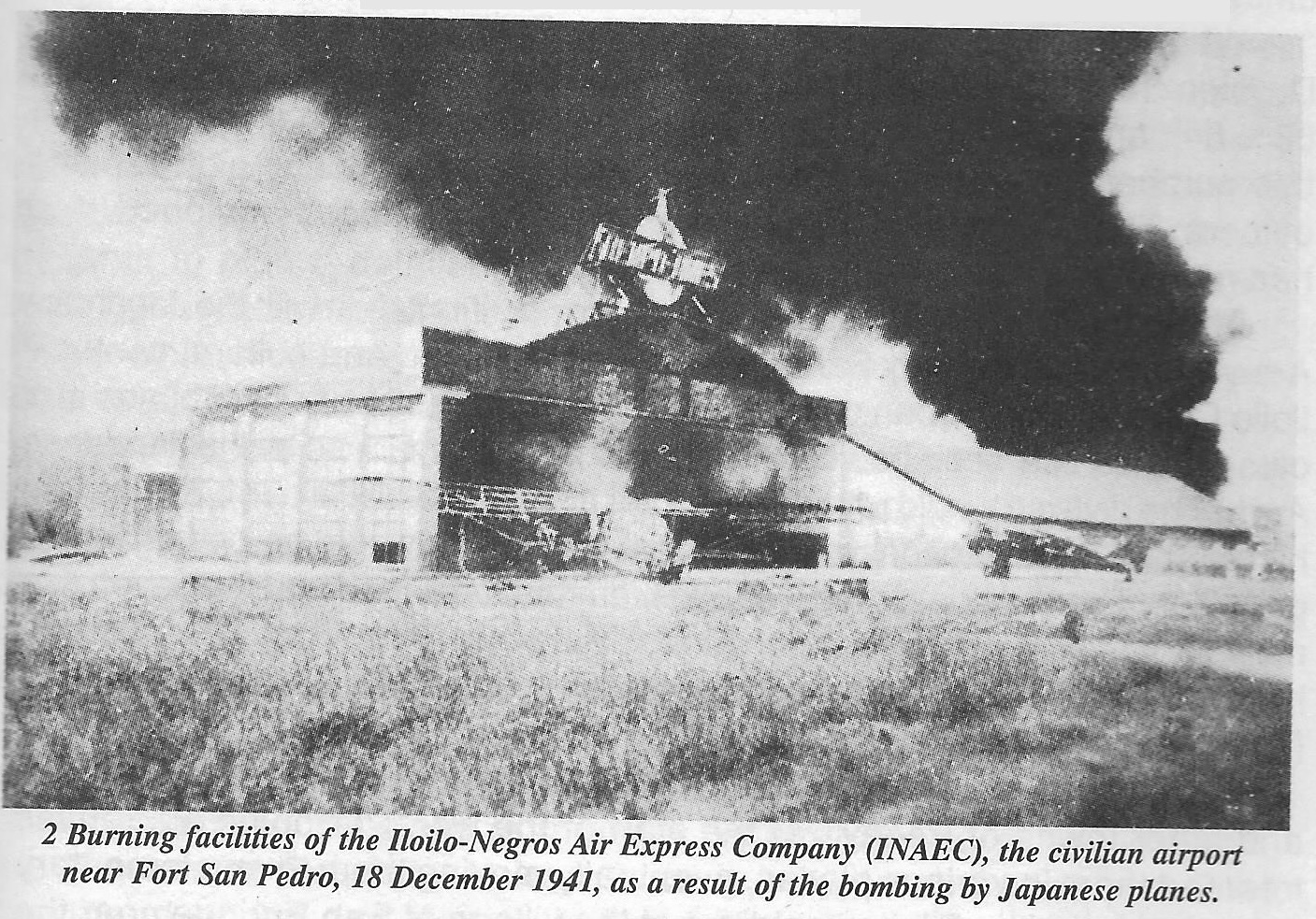

On December 18, 1941, ten days after the start of the Pacific War, 36 Japanese Army (JA) planes raided lloilo City. They accurately bombed and strafed the military airfield at Mandurriao, a civilian airport near Fort San Pedro, the fuel storage tanks at La Paz and the harbor facilifies along the Iloilo River. The incursion covered Iloilo City with flames and smoke, wounded or killed about a hundred people, and created chaos throughout. Some civilians with guns fired like lunatics at the passing airplanes.

2. Burning facilities of the Iloilo-Negros Air Express Company (INAEC), the civilian airport near Fort San Pedro, 18 December 1941, as a result of the bombing by Japanese planes. |

At about the time the Japanese planes bombed Iloilo City for the first time, the 61st Division (commanded by Brigadier General Bradford G. Chynoweth) of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) was stationed to guard the island of Panay. It consisted of the 61st to the 65th Infantry Regiments, transport and other units of the Philippine Army, elements of the US Army as civil as the Philippine Constabulary (PC). After the Japanese 14th Army began landing in Luzon on December 1941, the 61st and 62nd Infantry Regiments were dispatched, in February 1942, to Cagayan de Oro as part of a plan to strengthen the island of Mindanao. With his appointment as commander of the Visayas forces in March, Gen. Chynoweth moved to Cebu. His former chief of staff, Col. Albert F. Christie, succeeded as the commanding general of the 61st Division and was promoted as probationary Brigadier General.

| Under American administration in the early 20th century, Panay Island was divided into the provinces of Antique, Capiz and Iloilo. The present island-province of Guimaras was yet a part of Iloilo. Under the Commonwealth, the 61st Division was basically composed of the Philippine Army, with some US Army officers and men attached as instructors, including a few Philippine Scouts. |

| Both Kumai (1977) and Manikan (1977) refer to this promotion of Christie as Brigadier General, although no known official records support this. Subsequent messages to him were addressed to "Colonel" Christie. |

With the outbreak of the war, the 61st Division’s strength increased. Although composed of USAFFE and PC officers and men, many reservists and graduates of universities and high schools who had undergone military training were mobilized as probationary junior officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Other volunteers were also enlisted as soldiers.

When the Japanese Army landed on Panay in April 1942, the 61st Division under Colonel Christie had about 8,000 men organized into the 63rd, 64th and 65th Infantry Regiments, and one provisional regiment. Of this number, only a few were Americans who were mostly high-ranking officers. The division was not well trained and was poorly equipped, and had no artillery.

Thus, the 61st Division decided to avoid any confrontation with the Japanese Army. It planned to bomb Panay’s political, economic and cultural center–Iloilo City and other urban centers as well as vehicles like trucks, buses and cars–as part of a ‘scorched earth’ policy, to prevent their use by the Japanese Army. The division would retreat to the hills around Mount Baloy (1,728 meters high). Should the Japanese Army defeat them, they would go on fighting as guerrillas. The division stored weapons, ammunition, food and fuel, even rice mitts, in the mountains east of Mount Baloy. In early April, the division headquarters moved from Iloilo City to a village called Misi in Lambunao, Iloilo (about 48 kilometers north of lloilo City).

| A village in the Philippines is presently known as barangay, previously it was called a barrio. The mountain village of Misi is southeast of Mount Baloy that lies on the Madya-as range, bordering the provinces of Antique and Iloilo. |

There were around 470 Hôjin (resident Japanese civilians) in Iloilo City and other towns of Panay. At the start of the war, Philippine authorities interned them in various places, eventually moving them to an elementary school guarded by Filipino soldiers at the village of San Enrique near the town of Passi. After the fall of Bataan, the Hôjin policed each other when Filipino guards were removed. This was to prevent disorder and a repeat of what had happened in Davao where a Filipino soldier killed some of the resident Japanese.

| San Enrique is now a town or municipality, separate from Passi, which has become a city. |

On the day of the Japanese landing in Panay, April 16. 1942, the morning edition of the Panay Times carried anti-Japanese articles. The editorial affirmed: ‘It may be a matter of days before the Japanese Army will invade Panay. Japan’s success in the war on Luzon was due to the Japanese Army’s commandeering and using automobiles.’

1.2 The Japanese Army Lands In Panay

The Imperial Japanese Army dispatched the 14th Army to the Philippines under the command of Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma. The 14th Army had estimated the enemy force in Panay to be made up of two infantry regiments and one artillery regiment. As with other islands of the Visayas area, the Japanese Army had neither a workable knowledge of the shape and other circumstances nor any proper military topography of the island of Panay. It only had fragments of information on the enemy situation obtained through spies. These circumstances made it impossible for them to plan a detailed campaign. Hence, the Japanese Army only had a general outline for their movement into the Visayas. Operating forces were to decide on the details of the campaign on Panay upon their landing on the island.

With the capture of Corregidor came the plans for the invasion of the Visayas and Mindanao areas. Accordingly, from among the incoming reinforcing troops, the Japanese Army directed to Panay the Kawamura Detachment from the 5th Division that had completed the occupation of Singapore, along with the Kawaguchi Detachment of the 18th Division that had been involved in the takeover of the island of Cebu. Major General Saburo Kawamura, commanding the 9th Infantry Brigade, was assigned as overall commander.

According to the plans of Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo, the Kawamura Detachment was to carry out the operation under the command of the 14th Army until mid-May. Then, together with the Kawaguchi Detachment, it would move to operations in New Caledonia. Notably, these plans presumed that these forces would speedily engage and subdue the USAFFE in Panay and Cagayan de Oro on the island of Mindanao and occupy strategic positions in these two islands.

The 41st Infantry Regiment from Fukuyama City in Japan was the core of the Kawamura Detachment that departed from Singapore on March 27. Escorted by Destroyer Division 24 of the Japanese Navy, they arrived at Lingayen Gulf on April 5. The naval escort consisted of the flagship, the light cruiser Kuma, three destroyers, a torpedo boat, and an auxiliary seaplane carrier. It was here where army and naval authorities concluded agreements on the Panay landing operation.

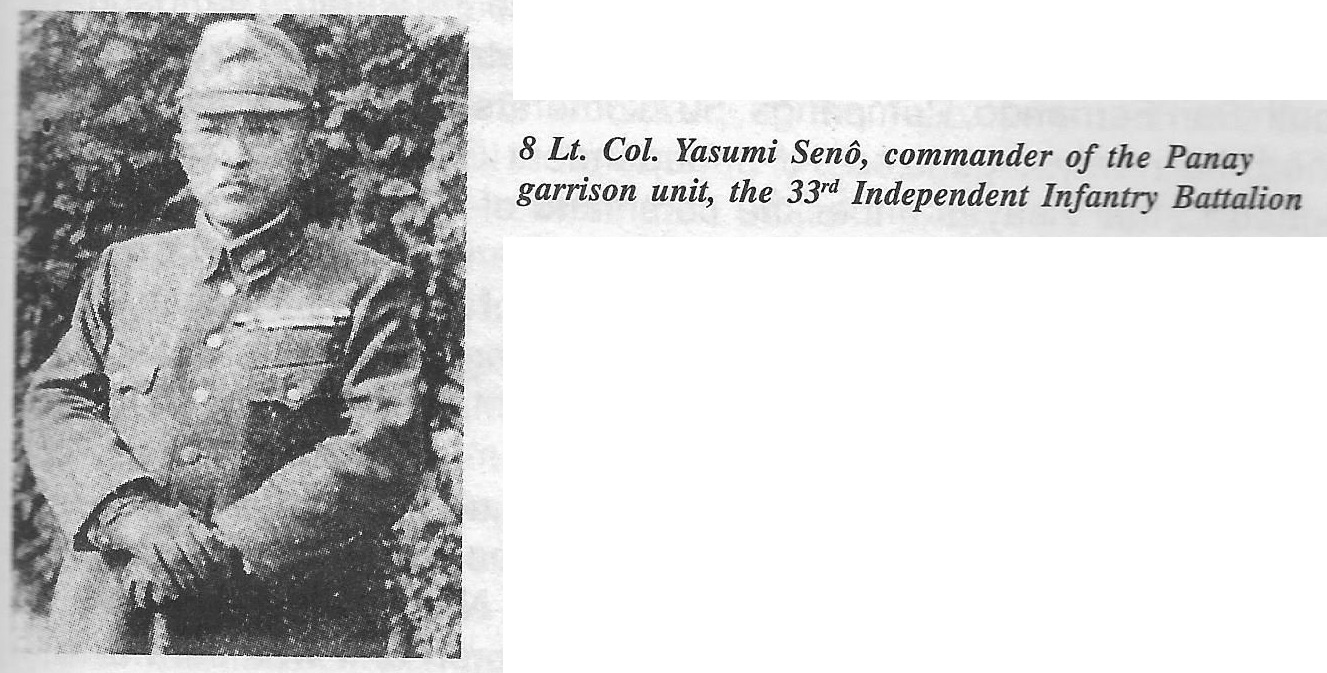

The main force was to land on the coast west of lloilo City, and a detachment was to land at a beach near Capiz. A force was to occupy the San Remigio copper mine in the province of Antique following a strong recommendation from the Japanese Military Administration (JMA) or Gunsei Kambu in Manila. Under General Kawamura’s command, the 33rd Independent Infantry Battalion (110) headed by Lieutenant Colonel Yasumi Senô was to serve as the Panay garrison. Hence, a portion of this battalion was ordered to land at San Jose, Antique. The 33rd IIB was one of four battalions belonging to the 10th Independent Garrison unit that accompanied the Kawamura Detachment to occupy the Visayas.

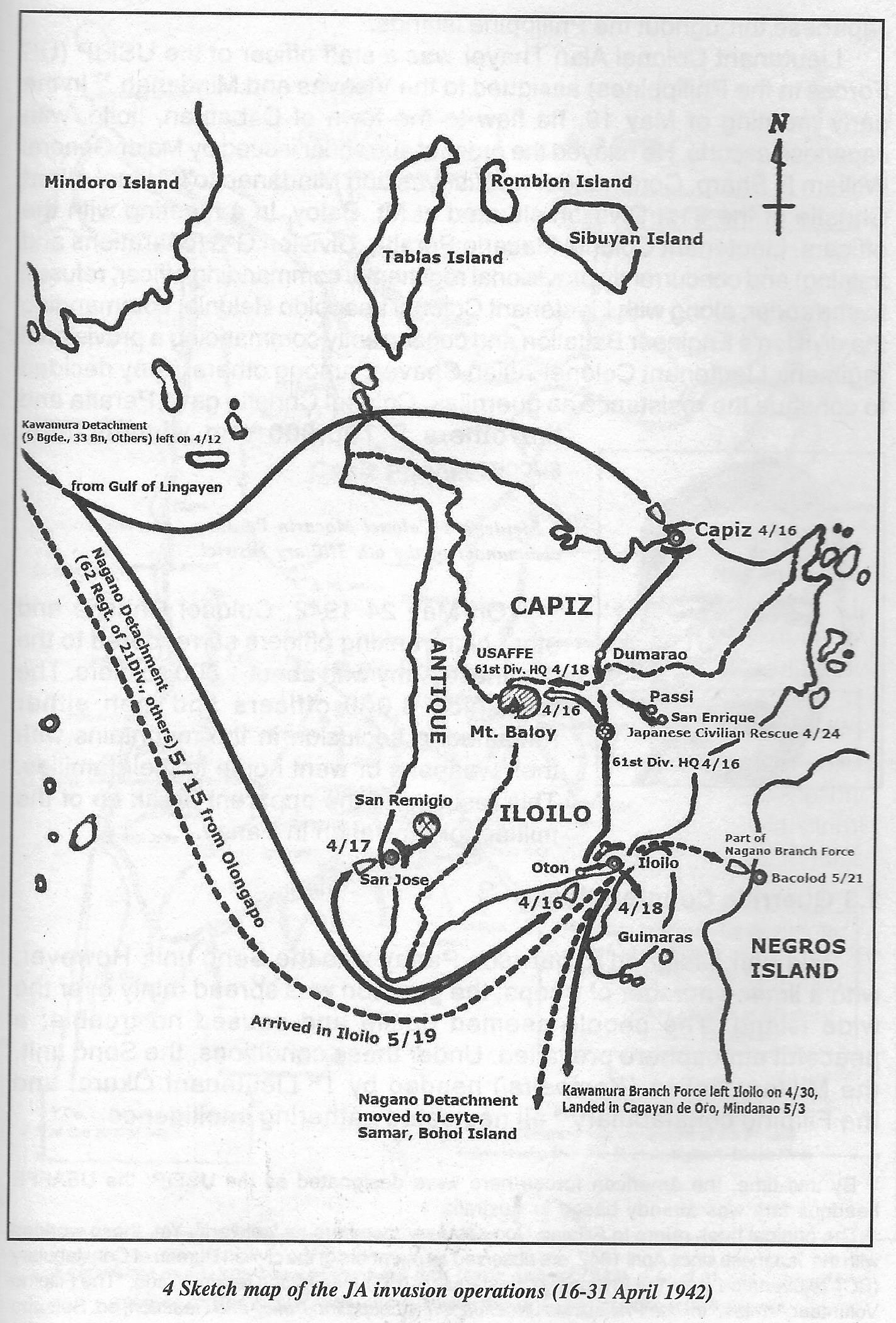

The Kawamura Detachment, on board ten transports in a convoy escorted by Destroyer Division 24, sortied from Lingayen on April 12 and, in one line, headed south. Two days after its departure, the radio announced news of the Kawaguchi Detachment’s successful landing in Cebu. On April 14, while off Mindoro, a section of the convoy broke off to head east for Capiz.

At 2 a.m. of April 16,1942, the main convoy anchored off the village of Trapiche near the town of Oton, 13 kilometers west of Iloilo City. There was not a flicker of light on the coast, the coconut grove was dark and one could only see the stars in the sky. The convoy caught the enemy by surprise and not even a single shot was heard. The landing force boarded their landing craft in darkness and went ashore. By dawn, all the forces were ashore and landing operations were completed. Then, the forces bound for Iloilo City marched into the Oton town center.

Also before dawn on April 16, a unit of the detachment (the 2nd Company of the Seno unit, or the Takayema unit as it was sometimes called) landed without bloodshed in Baybay, three kilometers north of the town of Capiz. Soon Japanese troops occupied the provincial capitol while the main strength of the forces headed south along the main road towards lloilo City.

On news of this development, the Filipino soldiers carried out their plans. They set fire to the stores on the main streets of Iloilo City as well as sugar warehouses along the Iloilo harbor area. Finally, after having blown up the bridge that separated Jaro and La Paz from the city, they retreated into the mountains inland. Amidst the smoke and fire, local residents evacuated from the city in great confusion. Poor residents who remained became violent looters and bandits, breaking into and ransacking residences and shops in Chinatown, before eventually withdrawing from the city.

The Japanese invasion forces split into two at Oton. The main strength of the Kawamura Detachment headed north while elements of the Seno unit–the 3rd Company (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Jôdo Takahashi) and 4th Company (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Matao Asahi)–entered Iloilo City later that morning.

The central area of Iloilo City that included the Chinese business district was razed and was still burning. The fire was likely to spread further and no one could do anything to stop it. Burnt electrical posts and wires lay on the roads, making it impossible for vehicles to pass. Fire had consumed the warehouses along the waterfront and the acrid smell of the scorched sugar scattered over the road filled the air.

The Japanese Army, led by light tanks, entered the city and proceeded to conduct mopping-up operations (sotô). However, the face of the enemy was nowhere to be found. When the Japanese forces gathered in front of the church by the city’s plaza, the soldiers shouted three cheers (banzai) while the city was engulfed in dazzling flames, dark smoke and the sweet sour odor of burnt sugar. There were no electric lights, no water in the city of Iloilo that night.

In the evening of the 16th, the front line units of the main strength of the Kawamura Detachment that had headed north from Oton advanced to the town of Lambunao, 48 kilometers north of Iloilo City. On the next day, the 17th, the detachment charged north and south like a tempest through the Iloilo plain and reached Dumarao, Capiz, 30 kilometers south of the capital town. Also on April 17th, the 1st Company of the Senô unit (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Osamu Nonomura) landed at Hamtic, south of San Jose. Antique. Facing no resistance, they occupied the town of San Jose. On April 18, an element of the detachment landed across the Iloilo Strait into the northern portion of Guimaras Island.

The Kawamura Detachment took over the central plains of Iloilo and attacked the Iloilo-Capiz national road and surrounding plain on April 23. Before this, on April 18th, there had been an encounter between elements of the Kawamura detachment and the USAFFE’s 1st Battallon of the 63rd Infantry Regiment led by Captain Julian Chaves at Mount Dila-Dila, some 20 kilometers west of the town of Calinog. Although the battle was close to the main USAFFE position, the Japanese Army retreated without attempting any attack. Thus undisturbed, the USAFFE forces at Mount Dila-Dila, became the core which the Panay Guerrillas would emerge. In the meantime, the Commonwealth Civil Government of the Province of Iloilo, led by Governor Tomas Confesor, was reorganized for resistance upon its retreat to the mountains of Bocari, Leon, Iloilo.11

| 11 The expansion of Confesor's government as the free government of Panay and Romblon had Gabriel Hernandez as Governor for Capiz and Tomas Fornier as Governor for Antique. Units known as Emergency Provincial Guards (EPG) served as this government's military arm. Felix B. Regalado and Quintin B. Franco, History of Panay (Iloilo City: Central Philippine University), pp. 243-252. See also Cesario C. Golez, Calvary of Resistance (Iloilo City: Cesario C. Golez, p. 16. |

3. Governor Tomas Confesor. |

On April 24, the Light Tank Force led by Second Lieutenant Nakane rescued the Hôjin interned at San Enrique. With their release, the conquest of Panay by the Kawamura Detachment was completed. The forces assembled in Iloilo City on April 25; and after the Hôjin gave souvenirs to the heroes of Singapore. The detachment left for Cagayan, Mindanao on April 30. Some of these men were later wiped out when transferred to Eastern New Guinea and Leyte.

Under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Yasumi Senô. The 33rd IIB of the 10th Independent Garrison unit took control over Panay Island. The battalion lacked equipment and training. On the other hand, the guerrillas were already organized about this time and were beginning to attack.

On the same day that the Japanese arrived, April 16, a Japanese Army plane made an emergency landing in the mountains near the town of Dingle, Iloilo. Young men from the town of Dumangas captured two crewmembers and took them home after offering them a meal and alcoholic beverages. When drunk, the same young men brutally killed and buried them near a pond. This incident was the first atrocity made on Japanese soldiers.12

| 12 A guerrilla account located this crash-landing in rice paddies of the village of Abangay, part of Pototan to the south of Dingle. Carrying the plane's machinegun and a pistol for two days, the pilot and gunner wandered into the swampy areas of Barotac Viejo and Dumangas. At Naluoyan beach in Dumangas, they met and ate green coconuts with a local group of young boys. However, the latter's interest in their weapons caused struggles in which the Japanese crew were overcome and buried in a fishpond. Golez, pp. 22-24. |

During the time that the Kawamura Detachment was operating in Panay, the Japanese forces in Luzon had launched a general attack on Corregidor. At Corregidor on May 6, 1942, US Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright surrendered all US and Philippine forces that had been resisting the Japanese throughout the Philippine Islands.

|

Lieutenant Colonel Alan Thayer was a staff officer of the USFIP (US Forces in the Philippines) assigned to the Visayas and Mindanao.13 In the early morning of May 19, he flew to the town of Cabatuan, Iloilo, with Japanese escorts. He relayed the order of surrender issued by Major General Willlam F. Sharp, Commander for Visayas and Mindanao to Colonel Alben Christie of the 61st Division situated at Mt. Baloy. In a meeting with the officers, Lieutenant Colonel Macario Peralta, Division G-3 (operations and training) and concurrently provisional regimental commanding officer, refused to surrender, along with Lieutenant Colonel Leopoldo Relunia, commanding the division’s Engineer Battalion and concurrently commanding a provisional regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Julian Chaves, among others. They decided to continue the resistance as guerrillas. Colonel Christie gave Peralta and the others P700,000 and wished them success.

| 13 By this time, the American forces here were designated as the USFIP; the USAFFE headquarters was already based in Australia |

|

On May 24, 1942, Colonel Christie and other high-ranking officers surrendered to the Japanese Army with about 1,800 soldiers. The remaining 6,000 officers and men either remained in seclusion in the mountains with their weapons or went home to their families. This resulted to the apparent break-up of the military organization in Panay.

1.3 Guerrilla Counterattacks

The unit assigned to garrison Panay was the Senô unit. However, with a limited number of troops, the garrison was spread thinly over the wide island. The people seemed docile and caused no trouble: a peaceful atmosphere prevailed. Under these conditions, the Senô unit, the Military Police (Kempeitai) headed by 1st Lieutenant Okura, and the Filipino constabulary14 all neglected gathering intelligence.

| 14 The original book refers to Filipino Constabulary members as 'soldiers'. Yet, those working with the Japanese since April 1942, are observed as members of the civilian Bureau of Constabulary (BC) 'rejuvenated' from the Philippine Constabulary (PC). See MotoeTerami-Wada, "The Filipino Volunteer Armies," in The Philippines under Japan: Occupation Policy and Reaction, ed. Setsuho Ikehata and Ricardo Trota Jose (Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1999), p. 59. |

|

During this period, there were repairs made on the ruins of war; the military administration over the whole island was proclaimed on June 16 and a grand parade of the Japanese Army was held. Personnel from the Ishihara Industries Company were sent from Japan, and development of the copper mines at San Remigio in Antique and Pilar in Capiz was started. The Shimamoto Shipbuilding Company took over the Iloilo shipyard; the Taiwan Railroad Bureau worked on the reconstruction of the railroad and the Iloilo-Passi line became operational. The Mitsui Bussan Company managed the harbor facilities and warehouses and started gathering sugar and buying copra. The Nippon Eoseki (Japan Textile Company), The Southern Airlines, the Philippine Transport Company (shipping), fuel companies and others began operating as they were dispatched to the area.

Japanese management also rehabilitated the bus companies that began to run trips to and from Iloilo. Other facilities also opened – bars, bowling lanes and Hôjin-operated comfort stations that employed Taiwanese and Filipino women. The Japanese Elementary School, headed by the headmaster Isao Kayamori, reopened classes at a high school building in La Paz.15

| 15 This was at the Iloilo High School, presently known as the Iloilo National High School. |

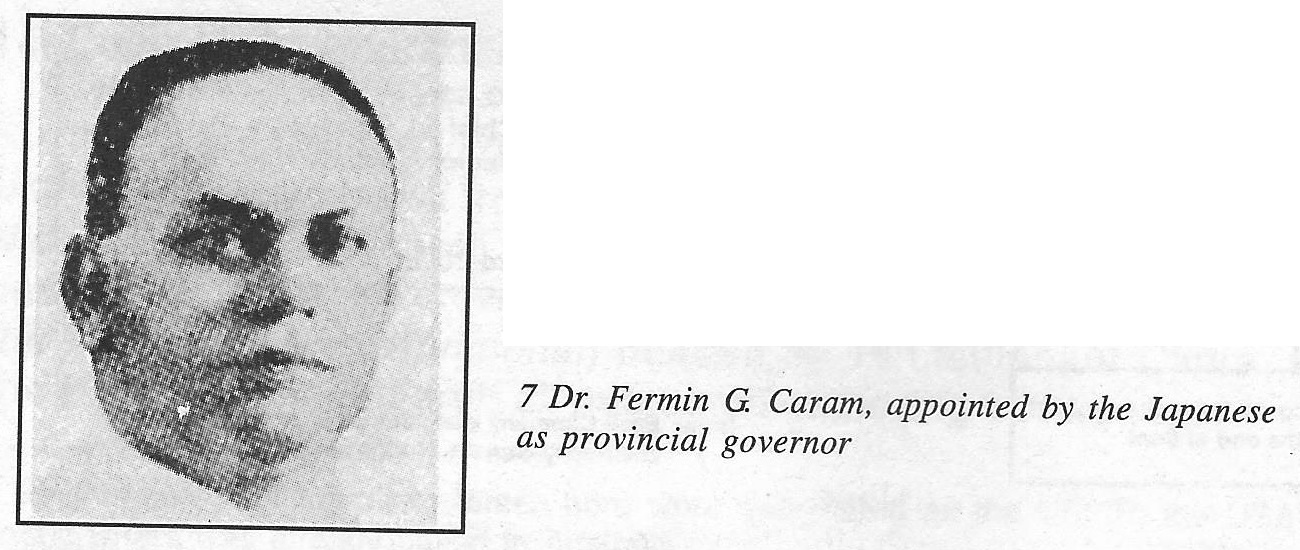

The Iloilo Branch of the JMA, through branch chief Captain Mihara, recommended appointments for provincial governor and city mayor.16 At this time, Captain Mihara was concerned with the fate of those facing the danger of living in the mountains. He recommended the appointment of Fermin G. Caram (who had returned to the city from the mountains) as provincial governor and Oscar Ledesma as Iloilo City mayor. Mayors of the other municipalities were also appointed. On the surface, it appeared as if Panay’s administrative machinery was beginning to function smoothly.

| 16 The local JMA office was at the Masonic Temple building that still stands, fronting the San Jose church across Plaza Libertad. |

7. Dr. Fermin G. Caram, appointed by the Japanese as provincial governor |

Although this was the situation in Iloilo City and in some municipalities, the main strength of the resistance lay beyond these areas. Both Colonel Peralta’s former 61st Division and Confesor’s civil government were preparing plans for counterattacks.

Early in June 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Peralta judged that the time for the reorganization of the resistance forces was good. Leaving the Agtugas Mountain near Calinog with 15 subordinates, he issued General Order No. 1 on June 10 to announce the formation of the Panay Free Forces with himself as the head. Within several days, he gathered around 2,000 former officers and men as well as other volunteers under his command.

Initially, while the island was in a state of anarchy, Lieutenant Colonel Peralta made it a priority to control the looters and bandits. With the cooperation of the police forces of the “free” civil government, they thoroughly contained the troublemakers. By the end of July, peace and order was restored and the local residents trusted Peralta’s military forces and Confesor’s civil government. They openly held dance parties to raise funds for the reorganization of the guerrilla forces and offered its soldiers and food. Neither the Senô unit nor the Kempeitai took notice of these activities. In August 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Senô reported to Manila headquarters “peace and order in Panay is quite good.”

The reorganized guerrilla forces restarted the fire of resistance on August 24 . According to guerrilla histories, guerrilla attacks in the middle of August were as follows:

On the 24th, the Calmay garrison in Janiuay was attacked, resulting in the killing of 20 Japanese soldiers and 1,000 rounds of ammunition taken. Governor Confesor’s brother, Patricio Confesor, waited for and attacked two trucks with Japanese soldiers near the base at Cabatuan, killing 10 and taking one truck. In Bitaogan, Passi, a train operated by the Japanese was assaulted and derailed. In Dueñas, a car carrying residents collaborating with the Japanese Army was ambushed. A Japanese soldier and all of the civilian passengers were killed. Weapons and ammunition were taken and the car was burned. Guerrillas also attacked the Dueñas garrison and ambushed two trucks carrying reinforcements. Fortunately, the Japanese troops on board were able to escape from the trucks. Other units attacked by guerrillas were the sentry post at the Jalaur River as well as the garrisons at Calinog and at the outskirts of Iloilo City.

On the 29th, guerrillas placed two boxes of dynamite on the train line connecting Iloilo Province and Capiz Province at Man-it, Passi, and blew train pulled by a diesel locomotive, with Japanese soldiers on board. (Killed in this incident were the Senô unit’s 4th Company commander, 1st Lt. Matao Asahi, 2nd Lt. Nishibe and 20 other officers (shôko) and men. Colonel Senô escaped harm since he was on board a coach in the rear of the train, some distance from the explosion). The guerrillas carried out many attacks and ambushes on other garrisons. The Senô unit suffered from many who were killed and wounded; they also lost many arms and ammunition. To provoke the people’s hatred and anger against the Japanese and to boost their fighting spirit, some guerrillas displayed the heads of Japanese who were beheaded in the town plazas.

During this period of guerrilla attacks, Japan’s war situation in the Pacific War received severe shocks. In the Battle of Midway on, June 5, the Japanese lost four aircraft carriers and one heavy cruiser, along with 3,500 casualties that included the best pilots of the navy. On August 7, American forces landed on Guadalcanal, and heavy fighting spread widely. Superior American forces pressured the Japanese Army to retreat.

Guerrilla attacks in Panay continued in September 1942 and the violence increased. Around 120 Japanese soldiers moving on the road south of Dueñas were ambushed by guerrillas on September 2nd. That same day, Japanese soldiers were also attacked at Banga-bante, north of Zarraga town (18 kilometers northeast of lloilo). On September 3, guerrillas raided the Japanese garrison sentry post at Malitbog. Calinog, as well as the sugar central at Janiuay. On September 5, the Pototan garrison received a huge assault followed by continuous fighting. On September 6, guerrillas assaulted the Maasin garrison, the sentry post at the Daja water reservoir (three kilometers west); they also wiped out the Janiuay garrison. The Santa Barbara garrison, 20 kilometers north of Iloilo City, was attacked on the same day, and the fighting here lasted for one week. On the 22nd, two trucks carrying Japanese soldiers were ambushed at Igtagmay, Sibalom in Antique (Adjutant Inayama of the 1st company, serving as representative of the commanding officer, was killed in action in this encounter).

In October, the guerrilla attacks continued. On October 4, the Sentry post at Mataraus Hill in Patnogon. Antique garrison was attacked. On October 5, the garrison of Capiz. Capiz–then held by the 2nd Company or the Takayama unit–was also attacked. (At about this time the Kalibo garrison in Capiz province–commanded by 1st Lieutenant Ito–withdrew without orders). The guerrillas not only attacked garrisons but also frequently attacked the sentry posts near Iloilo City itself. Gunshots could often be heard within the city.

The Senô unit barely made up one battalion, one that was hurriedly mobilized and dispatched to the front lines in the South. Because of the situation, the unit suffered increasing numbers of dead and wounded. The garrisons also repeatedly withdrew. Damages increased day by day, and the Japanese soldiers’ morale dropped as they became more and more afraid of the guerrilla attacks.

The guerrillas held ceremonies to celebrate their victories in the plazas of the towns that they recovered from the Japanese. Church bells rang and the American and Philippine flags were flown. Public offices were reopened, such as those of the town mayor, the town council, police, courts and so on. The civil administrative organization was reestablished, and by the end of September, administrative operations in the guerrilla-controlled areas returned to normal operations just as before the Japanese landing.

|

In early October, the Japanese-occupied areas were limited to the following: in Iloilo Province, Iloilo City, Pototan and Santa Barbara: in Capiz province, Capiz town; and in Antique province, San Jose town. Outside of Iloilo City, guerrillas surrounded the other four garrisons. Isolated, and with no aid expected, the situation was so bad that Japanese soldiers could not come out of their camps since it was too dangerous, particularly at night.

Sentry posts at the outskirts of Iloilo City were not the only Japanese positions facing raids day in and day out. The Senô unit’s headquarters in the provincial capitol suffered nightly guerrilla attacks launched from the opposite bank of the Iloilo River. Because of the inadequate strength of the Senô unit, men and boys from the local Japanese residents carried guns and were made part of the city’s garrison. Peace and order conditions suddenly deteriorated. The city residents evacuated and people no longer walked the streets. One had an eerie feeling of the city being a city of the dead. Guerrillas abducted Filipinas in the comfort stations whom they were considered collaborators. Because of this situation, a squad was assigned to escort students to and from the Japanese Elementary School.