during an event in Cabatuan Iloilo, around 1948 A guerrilla soldier who was among the first on the scene had carried away 3-year-old Toshiko Oshiro to his hometown of Cabatuan, where she was taken in by the Catalan family and named ‘Librada’ - Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay |

Amidst children’s cries, they picked through the wounded and corpses to recover those who survived.

Some Nisei children retrieved from the site that have been traced; parenthetically, they were given Spanish-sounding names by adoptive families evocative of having been resurrected or saved.

The children of Tokamatsu Kawakami were raised by nearby families: Mihoko (‘Salvacion’) and Sumie (‘Gloria’) with the Morenos, and son Tadanori (‘Salvador’) with the Cabreras.

Mihoko (5 years) and Tadanori (7 years) were old enough to remember that, fearful of the explosions and gunfire around them, they had fled from the group that night; upon returning when the guns were silent, they stepped over dead bodies to find their mother and younger brother among other acquaintances at the site.

From beside a bloodied woman, a very young boy was picked up by locals and turned over to the care of parish priest who gave him his name; ‘Lazaro Tuban’, though deemed of Okinawan origin, his identify was never verified.

Young Seizo Tôma, who grew up as Pablo Delgado in Negros, survived almost unscathed while his brother Diego sustained serious wounds.

With stab wounds on her side, Chiyo Saki, awoke from a faint to see unwounded but crying children being taken away by Filipino soldiers, particularly the 3-year-old Isao Onaga. She had carried him throughout the retreat to help her friend Natsu Onaga who had her own hands full with a 4 year-old son besides a baby; the Onaga boy she carried grew up as ‘Salvador Maravillosa’ with a local adoptive family.

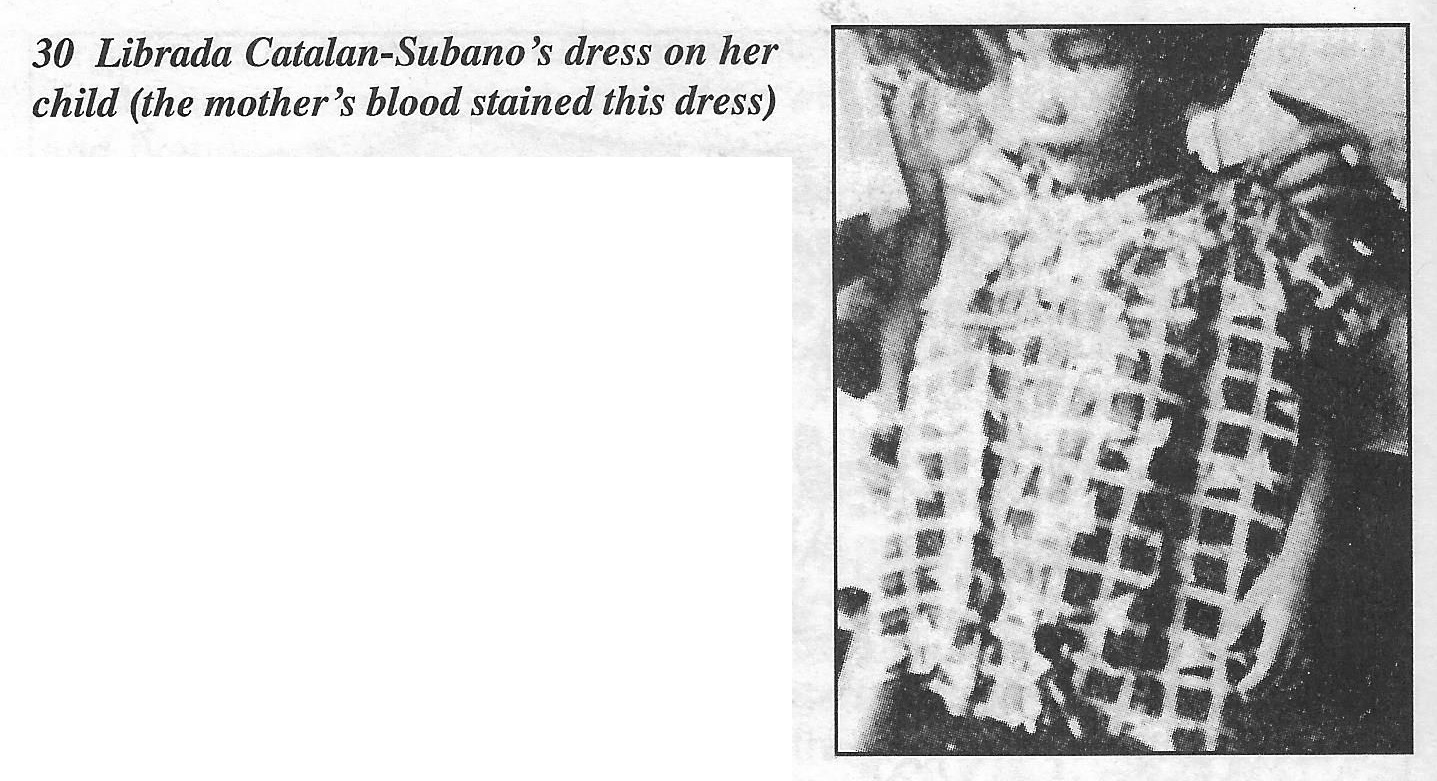

With sharpnel wounds, Tami Oshiro regained consciousness to find that her parents had died along with 2 of the 4 children with them who were missing. The fate of her son was not ascertained; but unknown at that time, a guerrilla soldier who was among the first on the scene had carried away 3-year-old Toshiko Oshiro to his hometown of Cabatuan, where she was taken in by the Catalan family and named ‘Librada’.

Kazuko Miyata (later Wakasa) was removed from the site where her mother and younger brother had died; she was brought by American troops with other wounded from Panay to a hospital in Cebu where she found her father with a bullet on his thigh from the escape from Iloilo City. Both recuperated and returned to Japan; but she still bears bayonet scars on her belly.

Other testimonies also come from those who changed their minds.

The teenage widow, Haruko Uehara Miyagi, made a last-minute decision to leave the site with her own widowed Filipino mother.27 With other imin, they somehow made it to Bocari.

|

27 See NHK 1988 documentary on Miyagi, and personal communication, 2003.

NHK. 1988. “Hahano kuni ga senjo datta: Firipin panai to tohiko (Mother’s Country was a Battlefield: Escape in Panay, Philippines).” 5th in Series on “Do you know the war? Messages to Children”. (Cited as NHK 1988) |

Ritszuko, one of the younger daughters of Kayamori, also made her way there with an older woman she befriended along the way, Kiku Minezoe (Yomiuri 1983 and NNN 1983).

Moreover, those who did not join the organized withdrawal fended for themselves.

Elderly men, like Reiichi Ishii, and Filipino spouses and children of the Aragakis, Fujimotos, Higas, and Umanos stayed with the nuns at St. Paul’s Hospital until American forces moved them to Asilo de Molo.

The good friends, Saburo Akamine and Hyoshiro Nakaya, had moved to the city when American landings were imminent. Since they did not wish to involve their families with suicide or imprisonment, they did not join the retreat nor sought refuge at St. Paul’s. Even if Akamine’s wife Margarita was 7-months pregnant, they moved around the city to evade the rounding up of remaining Japanese; the men were eventually imprisoned with guntai and other imin at the Iloilo Provincial Jail.

Most other imin were able to join the soldiers who successively gathered at the designated defense position in Bocari.

- Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay

Tracing the Roots of the Nikkeijin of Panay, Philippines

Librada Catalan-Subano's dress on her child (the mother's blood stained this dress). A guerrilla soldier who was among the first on the scene had carried away 3-year-old Toshiko Oshiro to his hometown of Cabatuan, where she was taken in by the Catalan family and named ‘Librada’ - Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay |

After the war, I looked for their parents and was able to establish the identity of two of the children: Salvador Cabrera and Salvacion Moreno, originally the Kawakami brother and sister, Tadanori and Mihoko. By then, however, their father Tokumatsu Kawakami in Kumamoto passed away in 1962.

At the time of his rescue, Salvador Cabrera had been in the first or second grade of the Japanese school. He described the situation as follows:

We were ordered to leave our school at San Agustin College to go to the mountains. I walked with Mother and other elderly people. Whenever we tried to rest along the way, soldiers ordered us to move faster and faster; so even when we felt awful, we walked on. The US forces started to shoot the area near us, so we all lay flat on the grass. Eventually, shells started to drop around us. The Principal of the school assembled Mother and others; they sang our National Anthem (Kimigayo), and he prayed. As shells fell around us, I ran away with my sister. We hid ourselves all night, and in the morning, when we returned to where Mother was, she and our younger brother were dead; other acquaintances were dead as well. Eventually , Ireneo Cabrera, who later became my stepfather, came and took me to his house. Vilda Moreno took my two sisters. (Another sister, Sumie, who also survived died young of disease.)

| 72 Mihoko Kawakami (Salvacion Moreno) now lives in the United States; Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano) has moved to Japan; and Isao Onaga (Salvador Maravillosa) now lives in Manila. Lazaro Tuban was reported missing as a crewmember of a cargo vessel. Of those found beyond the suicide site, the siblings Setsuko Miyazato (Salvacion Sequio-Solasito) and Kiyohiko Miyazato (Francisco Sequio) remain in Santa Barbara, Iloilo while Katsunori Miyata (Conrado Villaflor) lives in Iloilo City. |

- Toshimi Kumai

The Blood and Mud in the Philippines: 8.3 'Advance by Turning': Mass Suicide of the Hojin

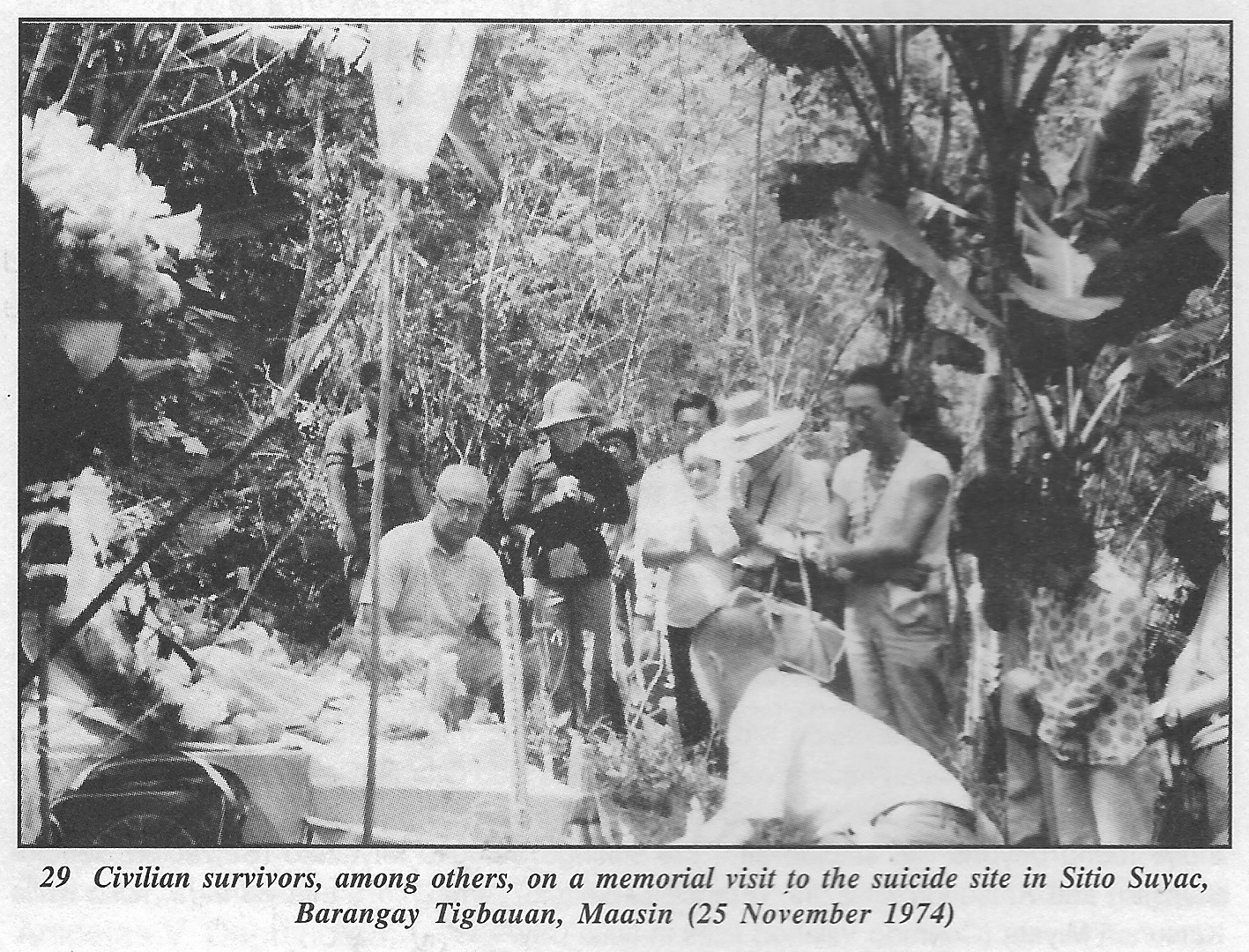

The tragedy of the mass suicide, and the fact that six Japanese orphans had been miraculously saved by local people and guerrillas and brought up to fully-grown adults, were widely reported by the mass media as a 'Human Love Story that bloomed in the Hell of the Panay War'. The warfare in Panay drew attention for the first time since the end of the war.

That report of the six survivors deeply moved all who had connections with Panay Island and prompted them to build a joint memorial of all the war dead of Panay. In addition, the Japanese Government dispatched a group to collect their remains.

| Children survivors of the jiketsu today are: Mihoko Kawakami (Salvacion Moreno), Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano), Isao Onaga (Salvador Maravillosa). The siblings Sumie (Gloria Moreno) and Tadanori Kawakami (Salvador Cabrera) and Seizo Toma (Pablo Delgado) have since passed away. However, the parentage of an unidentified male child survivor (locally known as Lazaro Tuban) was never confirmed. Among other Hojin children who survived elsewhere in Iloilo were the siblings Setsuko Miyazato (Salvacion Sequio-Solasito), Kiyohiko Miyazato (Francisco Sequio), and Katsunori Miyata (Conrado Villaflor). |

- Toshimi Kumai

The Blood and Mud in the Philippines: Prologue (2009 Edition)

Nine of seventy-one Japanese civilians who escaped a massacre by their·own troops told their story when they were treated by our medics.

Two of the survivors, both middle-aged women, who had been bayoneted testified that they were stabbed in their sleep. They had not been allowed to sleep for three nights and were kept marching all of the time.

On the fourth night when they were allowed to lie down, the Japanese soldiers killed sixty-two men, women and children.

They were discovered the next morning by one of our patrols who sent word for the medics.

Harry Robinson, Milton Ketchum and Ray Brown, a chaplain's assistant, journied six miles over the narrow carabao trail into the mountains to their aid.

- 160th Infantry Regiment

Gruesome evidence of the hopeless situation into which the enemy had been forced after his evacuation of Iloilo was furnished by the account given by two Filipino women, who with four Jap babies were the only survivors of the mass suicide and murder of 62 Japanese civilians in the area south of Jimanban. A group of Jap soldiers, their flight apparently slowed by the civilians whom they had forced or persuaded to evacuate with them from the city, were overtaken by our troops. Driven to a final stand, they stabbed and bayoneted the women and children prior to their own destruction by our fire.

WWII 40th Infantry Division

Panay Campaign, March 18 - March 28, 1945

A guerrilla soldier who was among the first on the scene had carried away 3-year-old Toshiko Oshiro to his hometown of Cabatuan, where she was taken in by the Catalan family and named ‘Librada’ - Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano) has moved to Japan - The Blood and Mud in the Philippines, Toshimi Kumai |

SALVADOR MARAVILLOSA WAS FOUND HERE (TOP RIGHT)

SALVADOR MARAVILLOSA WAS FOUND HERE (TOP RIGHT)28. Sketch of the mass suicide site (night of 21 March 1945) (based on interviews with local residents) |

29. Civilian survivors, among others, on a memorial visit to the suicide site in Sitio Suyac, Barangay Tigbauan, Maasin (25 November 1974) |