Toshimi Kumai (left), in 1974, with Source: The Blood and Mud in the Philippines |

`Anti-Guerrilla Warfare on Panay Island, Philippines'

Upon the 64th anniversary year of the end of the Pacific War, my prayers for the repose of all the victims of the warfare in Panay Island were very strong. They passed away without seeing the recent friendly relations between the Philippines and Japan.

As stated in this book, I got out of Sugamo Prison in 1954. The three years of the war, and the eight years and four months spent as a war criminal suspect and then as a war criminal, had thoroughly exhausted me. For some time, I was doing my best to forget all memories related to the war.

However, at Christmas 1972, I received an ardent inquiry from a bereaved family member of the Hojin, the Japanese residents who had immigrated to the Philippines before the outbreak of the war. She asked, 'How could I visit the place where the Hojin of Panay, including my parents, committed a mass suicide?'

As a member of the executive staff of my unit, I was in charge of carrying out operations when the US forces landed on Panay. Therefore, I had a strong sense of responsibility for the mass suicide (jiketsu) of the Hojin. Furthermore, this inquirer had graciously visited me a number of times while I was held in Sugamo Prison, a rare act of kindness the Japanese public then generally avoided. I set out to search for the spot of the mass suicide.

The year 1973 had already been more than 28 years after the war, so it was by no means an easy task. Fortunately, with the enormous assistance and support of the Japanese-Filipino citizens of Iloilo City and concerned members of the local Philippine armed forces, the point of the mass suicide was finally located at Sitio Suyac of Barangay Tigbauan in Maasin, Iloilo.

The tragedy of the mass suicide, and the fact that six Japanese orphans had been miraculously saved by local people and guerrillas and brought up to fully-grown adults, were widely reported by the mass media as a 'Human Love Story that bloomed in the Hell of the Panay War'. The warfare in Panay drew attention for the first time since the end of the war.

That report of the six survivors deeply moved all who had connections with Panay Island and prompted them to build a joint memorial of all the war dead of Panay. In addition, the Japanese Government dispatched a group to collect their remains.

| Children survivors of the jiketsu today are: Mihoko Kawakami (Salvacion Moreno), Toshiko Oshiro (Librada Catalan-Subano), Isao Onaga (Salvador Maravillosa). The siblings Sumie (Gloria Moreno) and Tadanori Kawakami (Salvador Cabrera) and Seizo Toma (Pablo Delgado) have since passed away. However, the parentage of an unidentified male child survivor (locally known as Lazaro Tuban) was never confirmed. Among other Hojin children who survived elsewhere in Iloilo were the siblings Setsuko Miyazato (Salvacion Sequio-Solasito), Kiyohiko Miyazato (Francisco Sequio), and Katsunori Miyata (Conrado Villaflor). |

I joined the group that collected the remains and held a memorial service at the site of the Hojin mass suicide. Afterwards, with the cooperation of former comrades and bereaved families, we put up a memorial at the site, and looked for the parents of the saved orphans. We somehow succeeded since many surviving relatives were found.

At the same time, praying that such misery of war would never happen again, I published a record of my war experience with the support of concerned comrades, friends, and through the special favor of the Jiji Press in 1977.

In 2005, when attention had moved to the Iraq War and when the prominence of the name of Panay seems to be quietly disappearing, I unexpectedly received a partial English translation of my book from Ms. Yukako Ibuki, who had been researching on the Allied POWs held by the Japanese during the war. Moved by her work, and with a wish to contribute to the history of Panay, I introduced Ms. Ibuki to Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay, Professor of the College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV). The latter brought in the help of Prof. Ricardo T. Jose of the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy of the University of the Philippines, Diliman. The three of them worked together and successfully finished the English version.

The Japanese soldiers will never invade the land of Panay again. I pray this book will become one of the precious records of Panay that I love so much. I express my sincere gratitude to the co-workers, Yukako Ibuki, Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay, and Ricardo T. Jose.

Toshimi Kumai

Former Captain and Adjutant Officer,

Japanese Army Garrison in Panay Island

PROLOGUE (1977 Edition)

By Toshimi Kumai, former Captain of the Imperial Japanese Army

Translated by Yukako Ibuki

Edited by Kan Sugahara

During the Pacific War, the Philippine Islands became a hard-fought arena between Japan and the Allied forces. Many of the decisive battles that governed the fate of Japan were fought here: at the beginning of the war, the capture of the Bataan peninsula and Corregidor by the Japanese Army (JA). Towards the end of the war, on the islands of Leyte and Luzon, and further, the battle of Leyte Gulf where Japan's Combined Fleet was defeated. Thus, the islands were tragic battlefields where the death toll was said to have been more than one-half million Japanese.

Over-shadowed by numerous accounts of these major battles, there are few or no records on Filipino guerrilla activities available in Japan. It is a little known fact to Japanese today that there was strong guerrilla resistance against the Japanese occupation of the islands. Consequently, their hostility against the Japanese played an important role in the decisive Philippine Campaign.

Local people significantly supported Filipino guerrillas across the archipelago. Furthermore, their efforts had direct approval from the headquarters of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. In effect, they were really part of Allied Forces personnel, supplied with weapons, ammunition and equipment transported by American submarines. It was unfortunate that the 170th Independent Infantry Battalion or the Tozuka unit (commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka), of which this writer was a member, had to fight the fiercest anti-guerrilla warfare on the island of Panay where it was garrisoned.

The guerrillas on Panay organized in April 1942, soon after the Japanese Army occupied the island. In August of the same year, they rose against the Japanese forces all at once. For about three years until the US Forces landed on Panay in March 1945, the Japanese Army garrisoned on the island and the guerrillas here fought many fierce baffles. In consequence, about 2,000 officers and men of the Japanese Army and about 1,300 of the Panay guerrillas were killed in action, and about 10,000 residents involved in the battles were said to have lost their lives.

The Japanese Army had to chase the guerrillas who were in close contact with the islanders, a situation that made an even fight impossible for them during daytime. Therefore, the Japanese Army had to carry out its encounters mostly at night. The guerrillas never succumbed to the Japanese Army despite the frequent punitive campaigns of the latter. As the American invasion neared, the guerrillas had better supplies of weapons and other equipment that soon overwhelmed the remnants of the Japanese Army. After the invasion of Leyte by US forces in October 1944, the main Japanese force abandoned Panay, no longer considering it as strategically worthy.

In the midst of this bitter situation, about 7,000 troops of the US 40th Infantry Division landed on Panay in March 1945. Although the numbers of the US troops and guerrillas that surrounded the Tozuka unit were ten times more than their strength, it broke through the cordon by outwitting the enemy and successfully moved to positions in the mountains. During this retreat, however, the protagonists fought fierce battles here and there that resulted in many casualties. Furthermore, about forty Hojin (resident Japanese civilians) tragically committed a mass-suicide.

US troops and guerrillas frequently attacked the Tozuka unit's mountain retreat. Nevertheless, the latter defended its positions well until they surrendered unconditionally only after the war had ended in early September 1945. Thus, the fighting on Panay Island ceased. Though the unit carried out anti-guerrilla warfare, almost all of its officers were blamed for brutality and were subjected to trial as war criminals. Seven of them, including group and unit commanders, were sentenced with the death penalty; six others, including this writer, were imprisoned with various terms.

The war crimes trial proceedings revealed the brutality of the Japanese Army. However, some cases were prosecuted unfairly because accused parties were blamed without sufficient clarification of the facts. The tragic warfare on Panay Island was extreme: one would die, if he did not kill the enemy.The real victims were the officers and men of the Japanese Army and the guerrillas as well as local residents; unavoidably drawn into the war, they were forced to fight for their lives.

As adjutant of the Tozuka unit, I directed the anti-guerrilla warfare and collected information on guerrilla activities. Through the conduct of my duties, I observed that as anti-guerrilla warfare became more relentless, the more the islanders who were closely allied with the guerrillas were forced to make a great deal of sacrifices. The higher headquarters' staff officers, who scarcely knew anything about the Chinese Army and punitive actions against bandits during the Sino-Japanese conflict, prepared almost all the planning of the major battles. Poor planning for the battles not only victimized the front line officers and men of the Japanese Army, but the guerrillas who confronted them and the residents who were involved in the battles as well.

This book is a reconstruction of my personal experiences in anti-guerrilla warfare, supplemented with material from Filipino sources. Citations came from published works, such as, The War in Panay by a former guerrilla officer, Jose D. Doromal, Panay Guerrilla Memoirs by Maximo G. Salvador, Calvary of Resistance by Cesario C. Golez, and parts of History of Panay by Felix B. Regalado and Quintin B. Franco. I have written this book praying for the repose of my comrades, the HOjin, the guerrillas and local residents who perished in the war, and the desire that such a deplorable war would never occur again.

In the months of November and December in 1974, as representative of a War-Dead Remains Collection Group dispatched by the Japanese Government, I re-visited Panay with former comrades and bereaved families to gather the abandoned remains of soldier comrades and the Kin who committed the mass-suicide on the island. Time heals all wounds. Twenty-nine years after the end of the war, the local residents' hatred against the Japanese had changed to friendship. They all welcomed our visit, and the municipal mayors and former guerrilla leaders were willing to guide us into the mountains. They even helped us dig out remains in the jungles. As a result, we were able to gather ninety-four remains of deceased soldiers, and perform a memorial service with the bereaved families at the scene of the mass-suicide.

However, it grieves this writer and others that about a thousand more remains of our comrades killed in action remain in the jungles of the island, literally covered by overgrown grasses. As one of the unit officers, I express my sincere remorse with pain in my heart about the general progress of the battles. When I especially think of those six children who miraculously survived the mass-suicide, brought up by the locals and now living in Iloilo City, my heart is full of apology for our failure to protect them. I also deeply appreciate the love and kindness of those who cared for them.

Mr. Yutaka Itsuki, a former comrade, and I took the photos in this book at the time of gathering the remains. The photos of the period under the early Japanese occupation are the courtesy of Mr. Shuji Takeshita, who was a member of the former Taga unit.

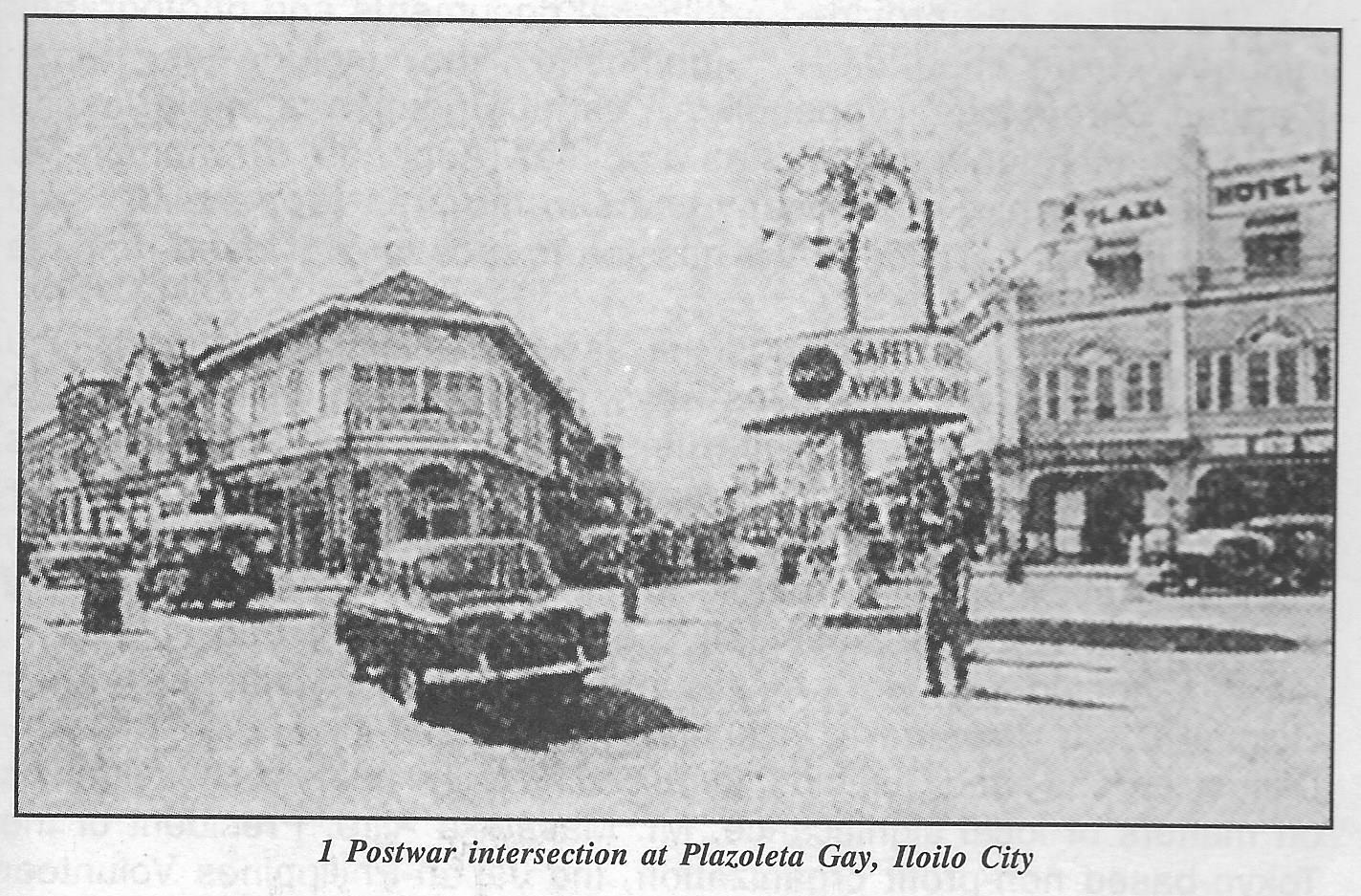

1. Postwar intersection at Plazoleta Gay, Iloilo City