NEWS OF JAPAN'S UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER

REACHES THE JAPANESE FORCES IN PANAY

The Emperor’s broadcast of unconditional surrender on August 15 came. I myself listened with the receiver on my ears and immediately reported the news to Colonel Tozuka. He quickly assembled the company commanders and told them the news. Instead of grieving over the surrender, the whole atmosphere at Bocari regained brightness. The faces of the soldiers of relief and the joy of liberation. That night each unit got out the best preserved foodstuffs and ate to their hearts’ content. The Japanese Army in Panay was at last going to be relieved of the day and night combat that they had endured for more than three years.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The 170th Battalion first learned of Japan's unconditional

surrender through radio broadcasts received sometime between the

14th and 24th of August (1945). All unit commanders were then called

together to furnish the headquarters with information on troop

strength and the disposition of subordinate units.

- Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa

On 16 August, 1945, Japanese Imperial Headquarters

announced the cessation of all hostilities and although an

estimated twelve days were needed for the orders to

reach all outlying Japanese outposts, the war was

officially ended.

- 40th Infantry Division

JAPANESE FEAR RETALIATION

With news of the surrender, the unit regained cheerfulness and some talked of returning to Japan. Nonetheless, there were also some voices fearing retaliation for atrocities committed by us on Filipinos. I myself was concerned about the clause in the Potsdam Declaration that said that those who killed or maltreated Allied POW and non-combatants would be tried at court. I asked Colonel Tozuka about it and he just laughed saying that it was meant for those who committed awful slaughter, and therefore, had nothing to do with us.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The Kempeitai commander, Captain Kaneyuki Koike, got out manual of the Army Criminal Law and opened to the pages near the end of the book. He went through the international agreements and read aloud the important articles based on the Geneva Convention on the treatment of POWs. Though I had heard of the existence of such agreements, it was the first time I heard about their content. I could not satisfy myself by just listening to them. Consequently, I read the articles on my own to the extent that I was able to talk to others about them. Colonel Tozuka then prohibited everyone from leaving his assigned position, not even a single step. He especially warned everyone not to have any conflicts with local residents.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

JAPANESE DON'T EXHIBIT ANY REACTION

TO THE NEWS OF JAPAN'S UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER

They had radios, and we believed they were well-informed about the development of the war.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

We were sure the enemy hold-outs at our front got the same report over their radios, but it elicited no apparent reaction from them.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

JAPANESE WAIT FOR INSTRUCTIONS FROM THE AMERICANS

We expected that some instructions would come from the US forces.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

JAPANESE LAST CASUALTY IN PANAY

On that same day (on learning Japan's unconditional surrender), however, our only communications engineer Corporal Takada of the headquarters’ wireless squad went missing when he left to look for food. The last news of him was that he got embroiled in a fight with soldiers at a village. He was killed in battle on the day the war ended to become the last of the unit’s casualties of the war in Panay.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

When we finally got back on Panay, our regimental commander, Colonel Stanton, who was a West Pointer, said, "The war is over. Starting this Saturday, we will have a parade in dress uniform every Saturday," and so, the next Saturday, … the first time I'd worn a tie in some time, we got on our dress uniforms and we were in suntans, so, it wasn't jackets or anything like that and we were standing parade and the General was making his inspection and he was just up to my [platoon]. At that point, I had the I&R platoon and somebody came rushing in, a Filipino farmer, … and talked to somebody and they finally interrupted, rushed up to the Colonel and said, "This farmer has just seen some Japs within, probably, a mile of our camp," and so, the Colonel turned to me and he said, "Bulling, take a patrol out and find out about this."

- Lt. Herman E. Bulling, I&R Platoon 40th Infantry Division (Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon)

So, I grabbed, probably, oh, maybe First Squad, it was only eight or ten people, and we went out on a patrol and I didn't really see anything, but I heard a shot and one of my guys had fired. He told me, later, he said, "The guy I hit had a bead on you, Lieutenant." I don't know whether to believe it or not, but he shot one and we captured one and we took the captured Jap back and I delivered him to our G-2 section and they started to interrogate him and they didn't believe them. They said, "Something is wrong with the counting. He must be uneducated, because it sounds like he's saying five hundred and there can't be five hundred men up in the hills, still." He was right; there were five hundred of them still up in the hills.

- Lt. Herman E. Bulling, I&R Platoon 40th Infantry Division (Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon)

ALL PLANNED OFFENSIVE AGAINST THE JAPANESE IN PANAY ARE SUSPENDED

All the planned offensive actions against the Japanese remnants were suspended, but we maintained close safeguards and observation over them.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

ALLIED FORCES ARE NOT SURE HOW THE JAPANESE IN PANAY WOULD REACT

TO THE NEWS OF JAPAN'S SURRENDER

Knowing the enemy's fanatical disposition, we were not sure how they would react to their government's acceptance of its first defeat at the hands of a foreign enemy in more than two thousand years of their country's proud military history. Would they simply lay down their arms and surrender peacefully in deference to their Emperor, or would they all band together and die in one last banzai attack against our installations? Or perhaps, might they not just commit mass hara-kiri in the tradition of the samurai?

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

ALLIED FORCES DECIDE TO TO CONVINCE THEM TO SURRENDER

The American Island Commander conferred with our Regimental Commander on actions to take to bring about the Japanese surrender. The first plan was to have a Japanese-speaking American of an intelligence unit get near the enemy group in the mountains where the most ranking officer was supposed to be and speak through a sound amplifier system to convince them to give up.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

JAPANESE-AMERICAN TRANSLATOR

TRY TO CONVINCE THE JAPANESE TO SURRENDER

Early in the morning two days later, An American sergeant of Japanese descent arrived at the forward command post in a jeep. We had him escorted by a squad of riflemen led by an officer who was familiar with the area, and we hired four civilians to carry his sound equipment and heavy storage batteries. I went along as observer.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

After about two hours of hike, we contacted our unit assigned to

stand guard over the particular enemy hideout. At

a suitable site, the American sergeant supervised the installation of the sound equipment, stringing up the loudspeakers to the branches of trees . As soon as everything was set, he

launched into his talk in pure Japanese , his voice reverberating in the wilderness . I remember when the Japanese used to do this sort of thing to us in the front lines of Bataan . I understood nothing

of what he was talking about, except that I thought he began by

introducing himself as I heard him mention his name and military grade

several times. I also caught some familiar sounding names, which perhaps

were among those our captors in Bataan tried to teach us but whose

meanings I had forgotten. From the tone of his voice and the expression

on his face, I gathered that he spoke in a friendly mode. He kept up his

talk for almost an hour, pausing now and then for only a minute or two

each time. When he was finished, we took down and repacked the sound

equipment and trekked back to the forward command post.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

On the way back I asked the sergeant to summarize to me what he

told the Japanese. "I gave them a run-down of the recent events in

their homeland, sir," he explained, "emphasizing the part about their

government having agreed, with the blessings of the Emperor, to stop

the fighting and surrender to the Allies. I asked them to consider the

uselessness and the dire difficulties of holding out in these mountains,

especially when their loved ones at home are now eagerly awaiting their

return after all these long years. I tried to convince them that the

United States Armed Forces and the Philippine Army assure them their

safety when they surrender. I informed them that while they are now

surrounded by our troops, if they lay down their arms and wave a white

flag, they will be escorted peacefully out of the mountains. I kept

repeating this theme not only in the formal official language but also

in the different dialects, idioms, and nuances I know."

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

JAPANESE DON'T REACT TO THE JAPANESE-AMERICAN TRANSLATOR

When no reaction came from the Japanese after three days (three days after the action of the Japanese-American translator), the American Island Commander informed the Regimental Commander they were dropping over the enemy sites leaflets that reiterated the message calling for their surrender.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

AMERICANS DECIDE TO DROP LEAFLETS

When no reaction came from the Japanese after three days (three days after the action of the Japanese-American translator), the American Island Commander informed the Regimental Commander they were dropping over the enemy sites leaflets that reiterated the message calling for their surrender.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

AMERICANS DROP LEAFLETS ON PANAY

In order to disseminate the surrender news to

the 1,700 odd Japanese soldiers on Panay, liaison planes

dropped information pamphlets throughout the island

stipulating that surrender panels be displayed by all units

and that a preliminary surrender meeting was scheduled

for 27 August. A surrender party of no more than twenty-five

Japanese was directed to report on that day to American officers

at the dam above Maasin.

- 40th Infantry Division

OBSERVATION PLANE DROPS LEAFLETS ON AUGUST 25, 1945

Surrender leaflets were dropped over the area by an American plane on the 25th.

- Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa

On August 24 or 25, a US observation plane flew over Bocari, as though looking for us. We spread a signaling panel and sent signals to the US plane. Recognizing the signaling panel, the plane’s body swung left and right and dropped a communication tube. Inside were instructions of the date and place where a representative of the Japanese Army was to proceed. There was also a written order signed by staff officer Hidemi Watanabe (then in Negros), which said, ‘By the order of General Yamashita, commander of the 14th Area Army, the Japanese Army should obey the instructions given by the US forces in your locality.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

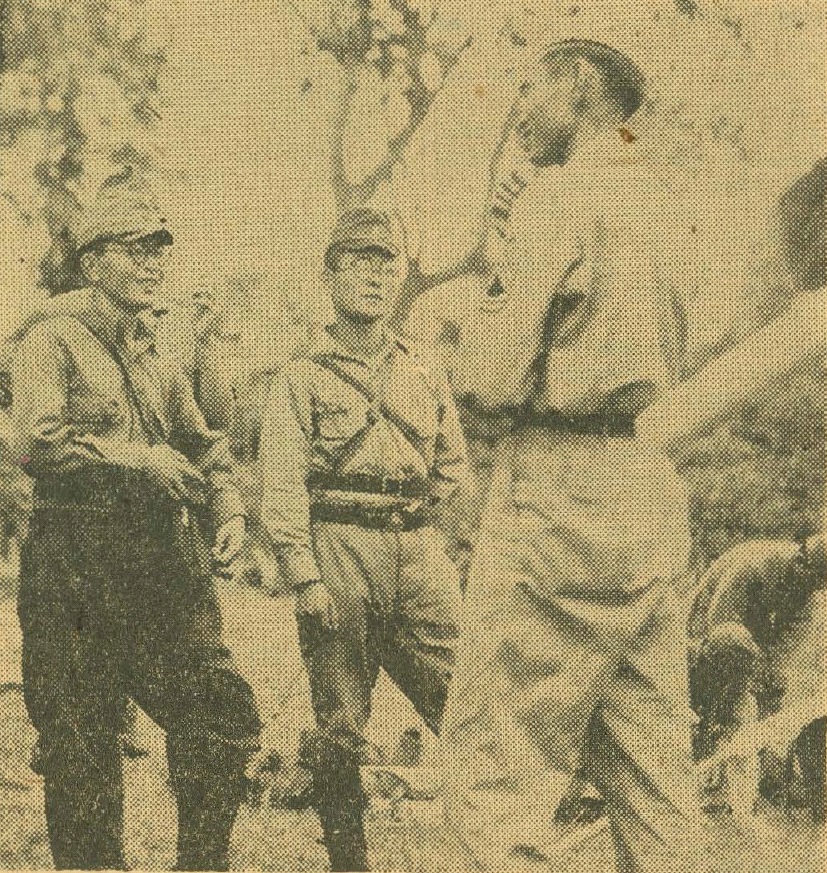

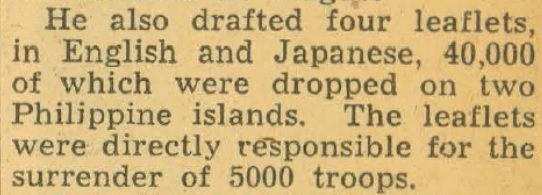

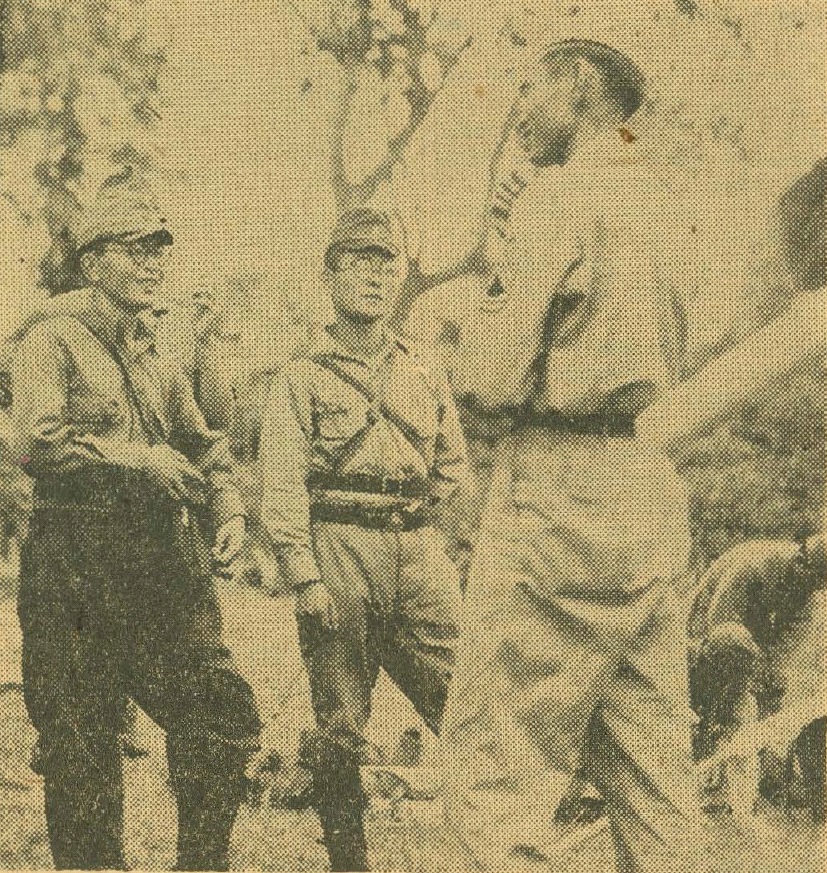

THE LEAFLETS WERE DRAFTED BY TECH. SGT. TERNO ODOW

T-Sgt. Terno Odow, rightmost, with Lieut. Sadayoshi Ishikawa and Capt. Kaneyuki Koike, at Daja, Maasin, on August 28, 1945

|

T-Sgt Terno Odow was the lead Japanese-American translator of the 180th Language Detachment.

He had drafted four leaflets, in English and Japanese, 40,000 of which were dropped on two Philippine islands (Panay Island and Negros Island).

The leaflets were directly responsible for the surrender of 5,000 Japanese troops.

He then drew the assignment of questioning a large portion of about 1,700 Japanese soldiers who surrendered in Panay Island.

|

IN THE LEAFLETS, THE JAPANESE ARE INSTRUCTED

TO SEND A PRELIMINARY SURRENDER PARTY TO DAJA ON AUGUST 27, 1945

In order to disseminate the surrender news to

the 1,700 odd Japanese soldiers on Panay, liaison planes

dropped information pamphlets throughout the island

stipulating that surrender panels be displayed by all units

and that a preliminary surrender meeting was scheduled

for 27 August. A surrender party of no more than twenty-five

Japanese was directed to report on that day to American officers

at the dam above Maasin.

- 40th Infantry Division

On August 24 or 25, a US observation plane flew over Bocari, as though looking for us. We spread a signaling panel and sent signals to the US plane. Recognizing the signaling panel, the plane’s body swung left and right and dropped a communication tube. Inside were instructions of the date and place where a representative of the Japanese Army was to proceed. There was also a written order signed by staff officer Hidemi Watanabe (then in Negros), which said, ‘By the order of General Yamashita, commander of the 14th Area Army, the Japanese Army should obey the instructions given by the US forces in your locality.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

OBSERVATION PLANE RETURNS

DROPS A WALKIE-TALKIE

FOR THE JAPANESE TO KEEP IN TOUCH

WHICH THE JAPANESE EMISSARIES USE LATER WHEN THEY COME DOWN FROM BOCARI

On the next day, the observation plane flew back. When we signaled the reply, ‘We have understood the instructions,’ the plane dropped a walkie-talkie (transceiver) to be used for contact.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

What we did was that we dropped a radio to them, so that they could contact Japan, because they didn't know the war was over, and we waited a couple of days.

- Lt. Herman E. Bulling, I&R Platoon 40th Infantry Division (Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon)

JAPANESE DON'T COME DOWN ON AUGUST 27, 1945

Still, no subsequent response came (after dropping leaflets).

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

JAPANESE FINALLY DECIDE TO COMPLY WITH INSTRUCTIONS

TO SEND EMISSARIES

Two days later (two days after August 25, 1945), it was decided

to comply with these instructions and to surrender.

- Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa

That day, the unit commanders’ meeting decided that, as previously planned, the Japanese Army emissaries would be Captain Koike of the Kempeitai, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I, with Sergeant Matsuzaki as the interpreter. The NCO cadet platoon led by 1st Lieutenant Horimoto, with Private First Class Ueki as the interpreter, would accompany us as our escort.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

Captain Unk Koike,

1st Lieutenant Sadayoshi Ishikawa, and 1st Lieutenant Toshimi Komai

were sent to the American lines to negotiate the turn-over.

- Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa

The Jap commander sent a party of 41 well-armed soldiers to the meeting. They were led by Capt. Kaneyuyi Koike and three first lieutenants.

- Staff Sgt. Alfred E. Hubbard, who met them at the bottom of the mountain trail at the river at Tinaan.

JAPANESE EMISARRIES LEAVE BOCARI

Early in the morning of August 30*, the emissaries of the Japanese Army in Panay, Captain Koike, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa and I, climbed down from Bocari and walked towards the town of Maasin.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

|

*Note:

This should be August 28, 1945

|

Moving in front, Private First Class Ueki carried a big white flag.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

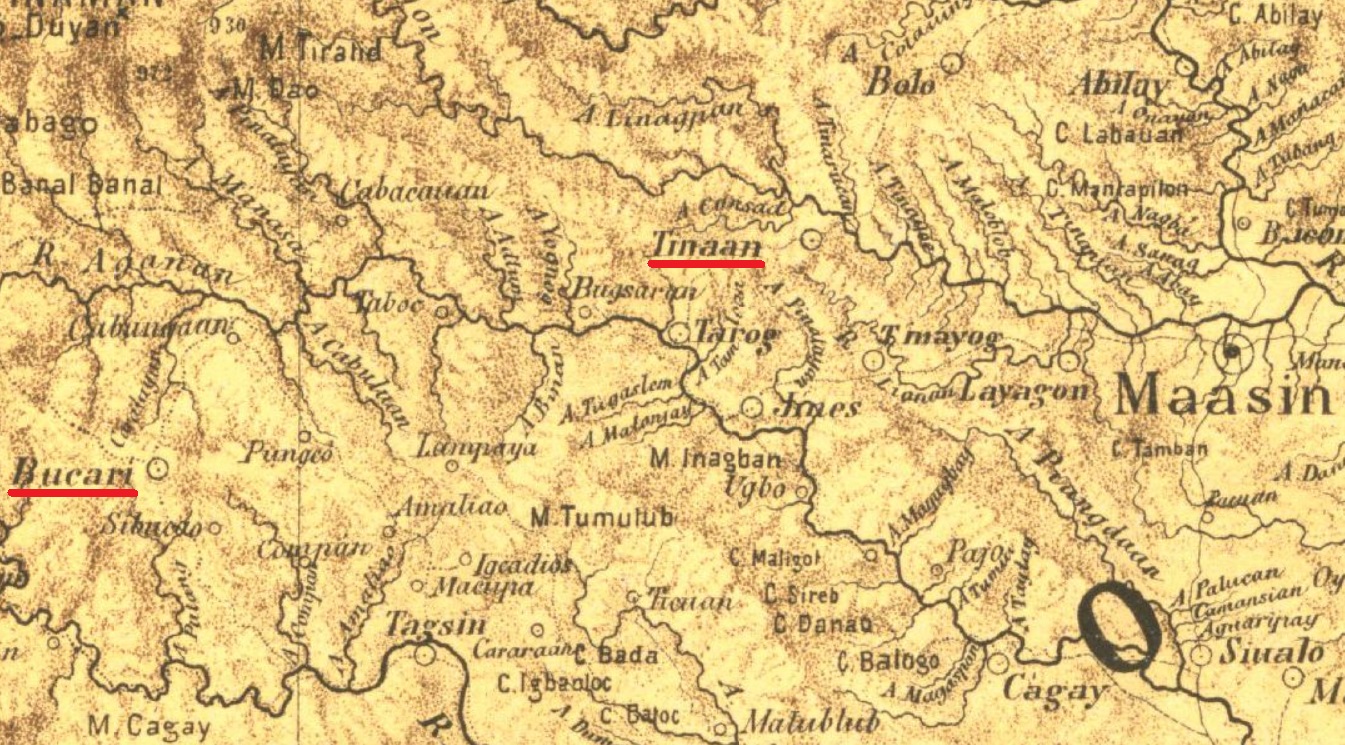

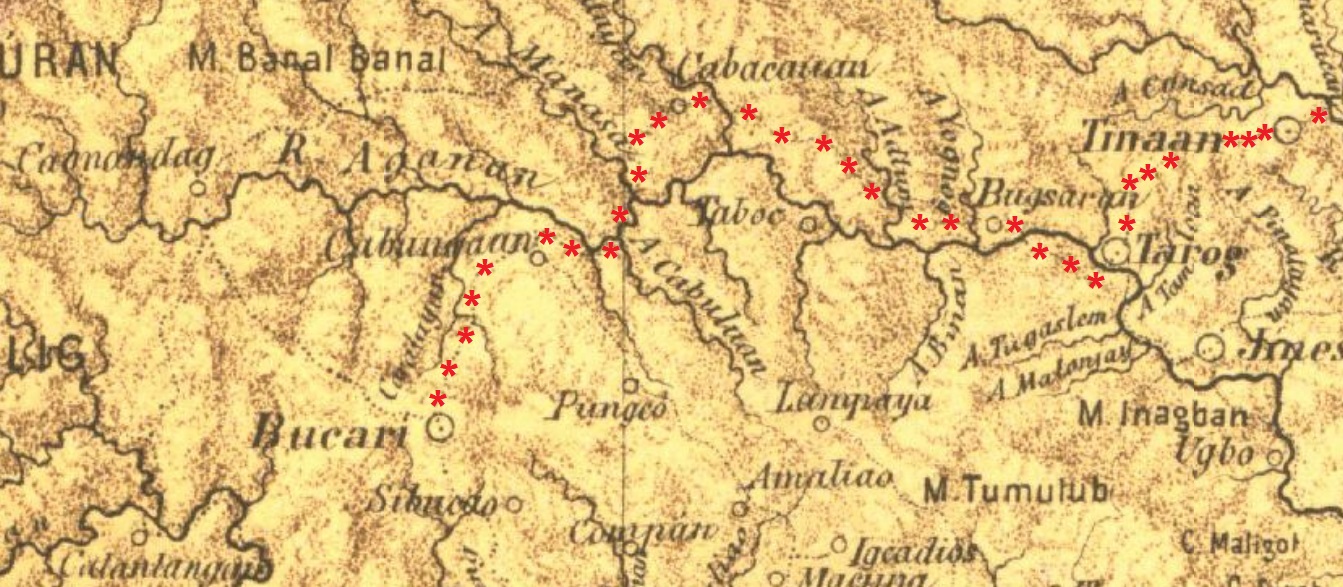

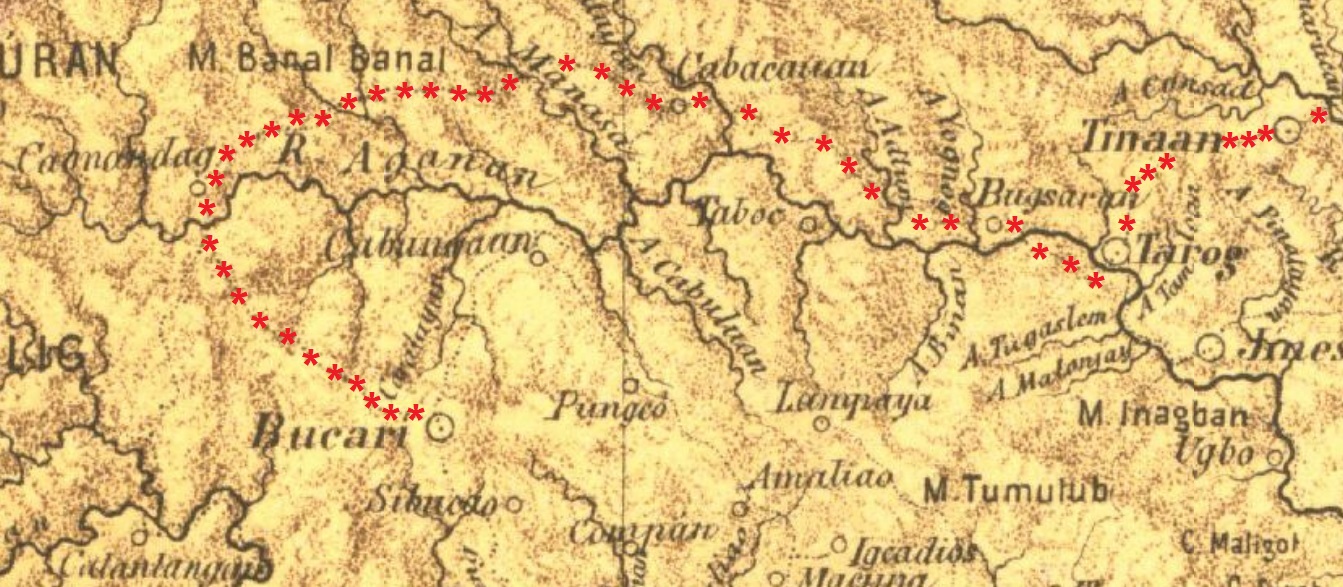

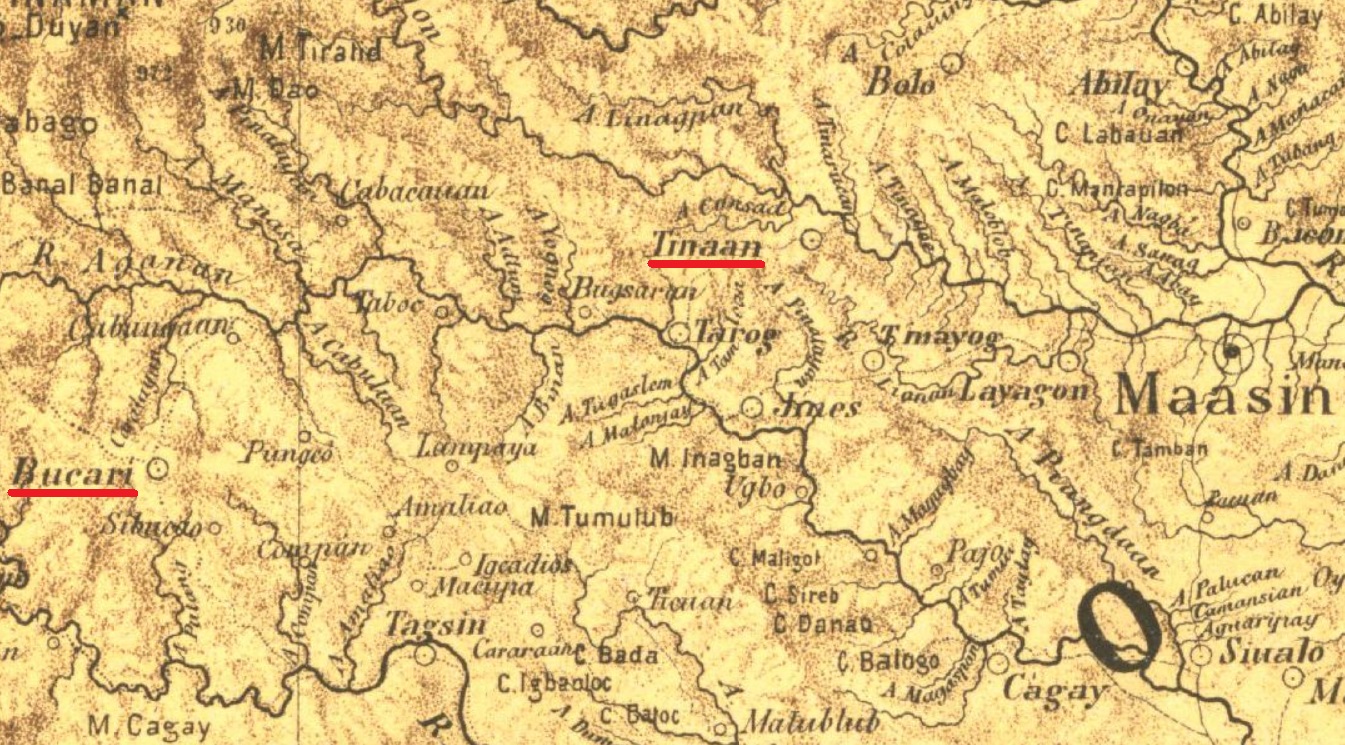

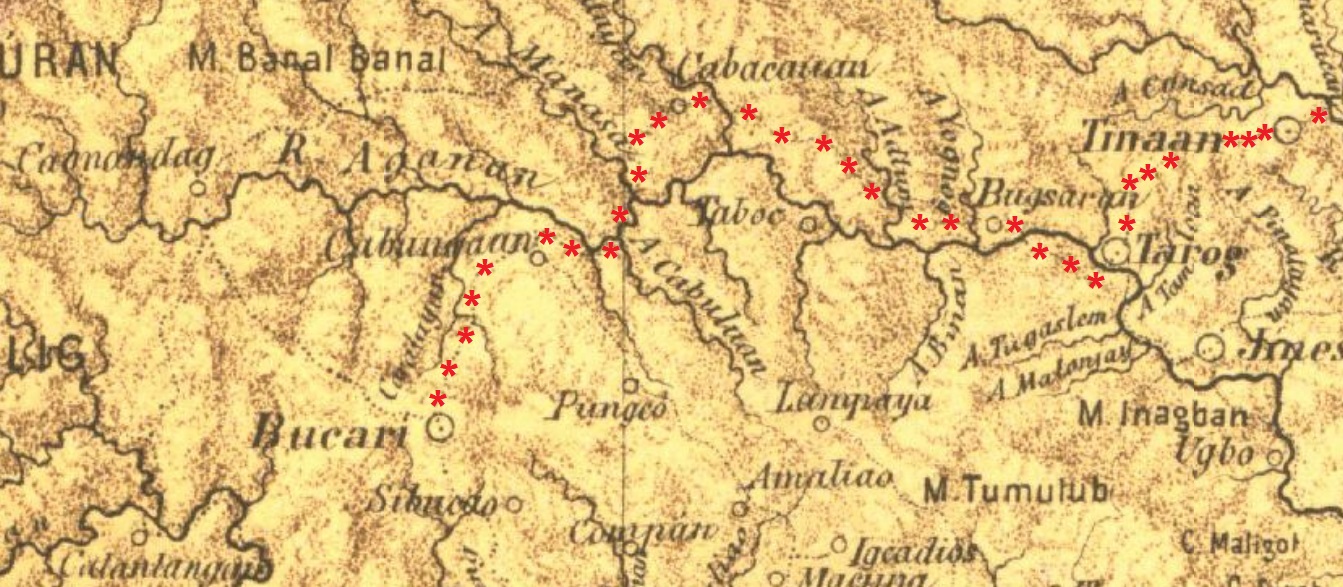

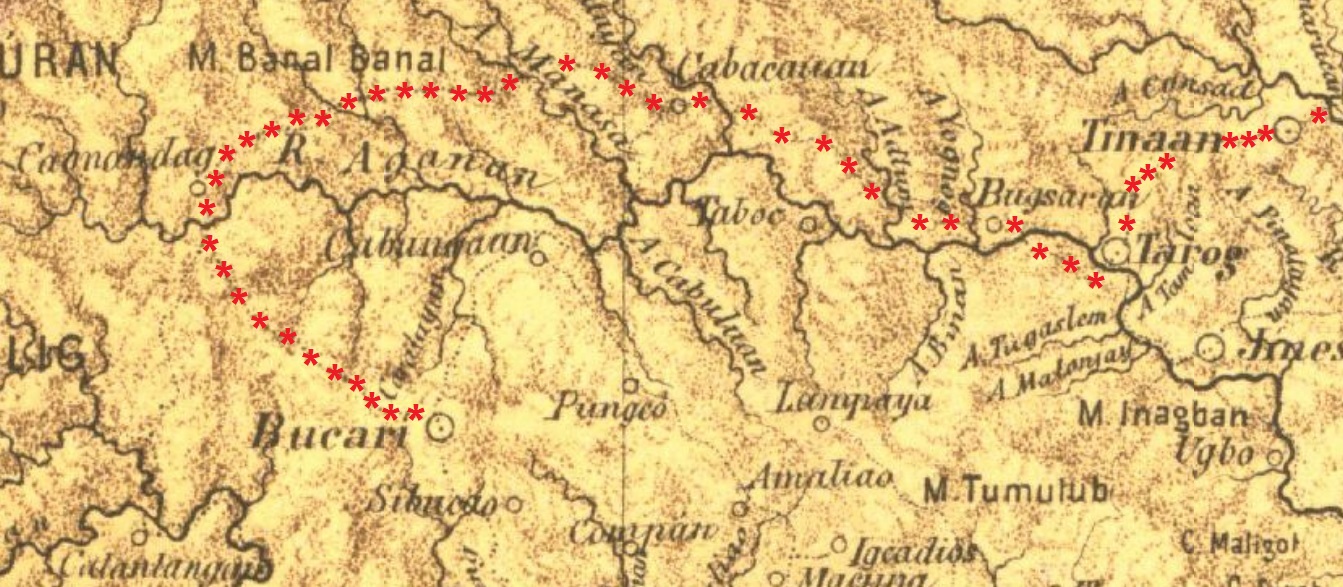

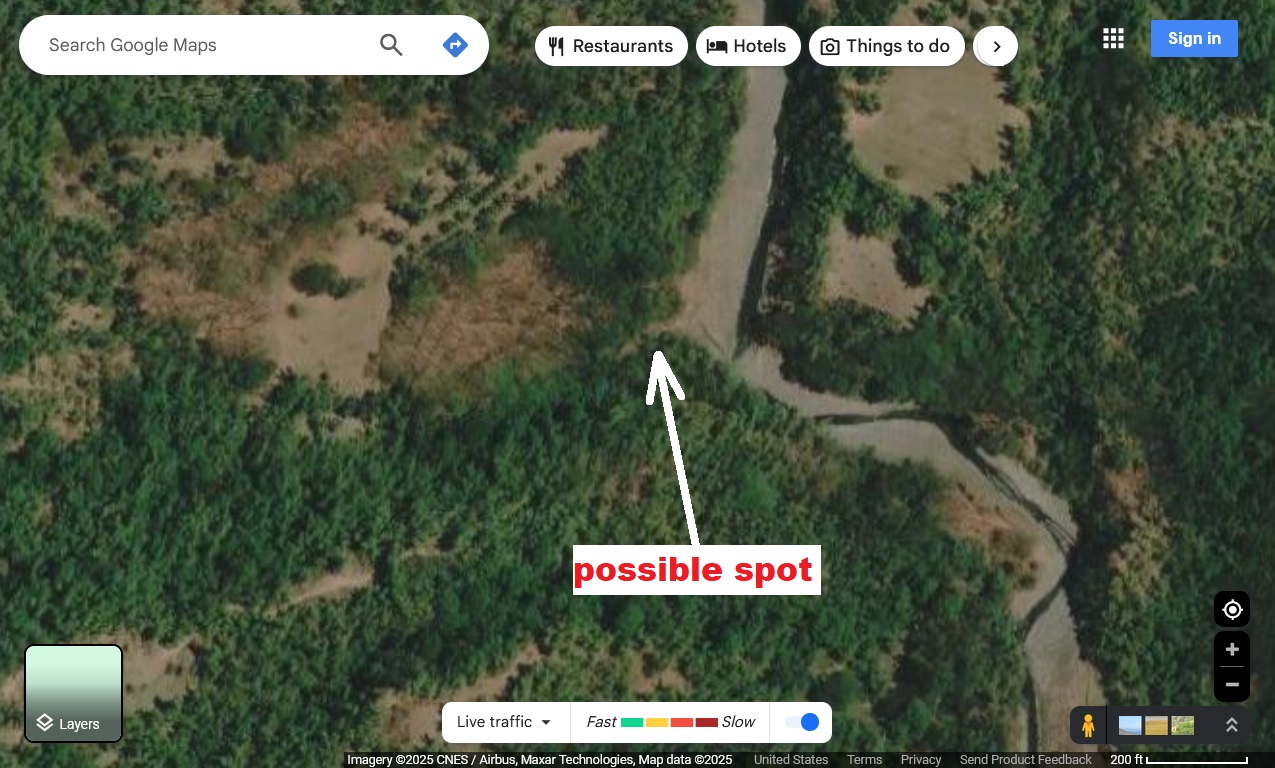

JAPANESE EMISSARIES TAKE THE MOUNTAIN TRAIL

FROM BOCARI TO THE RIVER AT TINAAN

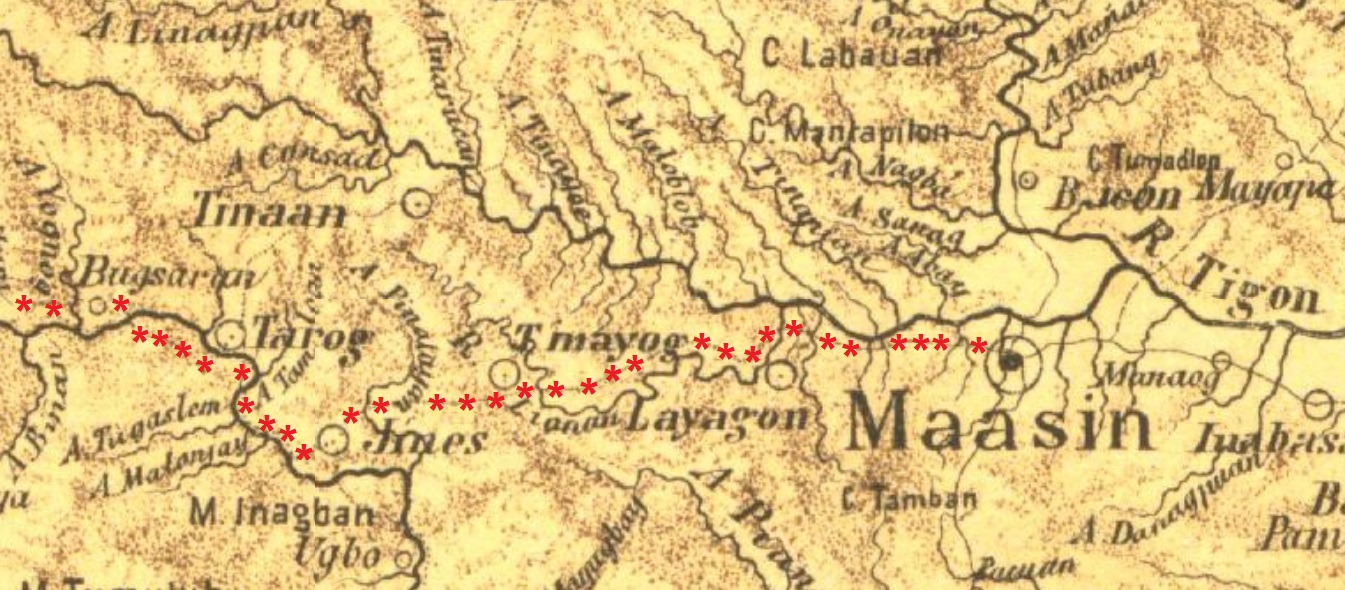

The Japanese emissaries would take the mountain trail from Bocari to the river at Tinaan.

There are two trails (shown on the map as dotted lines) from Bucari to Tinaan.

The shorter trail would take them from Bucari to Cabungaan to Cabacauan to Bugsaran to Tarog to Tinaan and to the river.

The longer trail would take them from Bucari to Camandag to Cabacauan to Bugsaran to Tarog to Tinaan and to the river.

There's a direct trail to Maasin plaza, passing by Tarog, Jines and Layagon but Tinaan and Daja were probably chosen by the Japs and/or the Americans to avoid passing or going into heavily populated areas, especially going into Maasin directly.

As Kumai had mentioned, "I pointed out that we were shot at by Filipino soldiers and civilians on the way down to surrender."

Capt. Eliseo D. Rio had mentioned Tinaan. According to Capt. Rio, Tinaan was at the foot of the mountain range, which would indicate that Tinaan was at the bottom of the mountain trail.

OBSERVATION PLANE DETECTS THE JAPANESE EMISSARIES

AS THEY COME DOWN THE MOUNTAIN TRAIL ON AUGUST 28, 1945

A DAY LATE THAN THEY WERE INSTRUCTED

JAPANESE USE THE WALKIE-TALKIE TO GET IN TOUCH WITH THE PLANE

As we advanced, the observation plane came to meet us. Sergeant Matsuzaki kept in touch using the walkie-talkie.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

On 28 August, a day late, an American reconnaissance plane observed the surrender party near the dam.

- 40th Infantry Division

They got in radio contact with them and we waited a couple of days, until we got a stockade built for five hundred troops

- Lt. Herman E. Bulling, I&R Platoon 40th Infantry Division (Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon)

JAPANESE EMISSARIES ARRIVE AT THE RIVER AT TINAAN

HERE THEY LEAVE THE TRAIL

AND TAKE THE ROAD-ALONG-THE-RIVER GOING TO DAJA

The mountain path widened to a road along the river as it was nearly the set time of our arrival at the appointed place.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

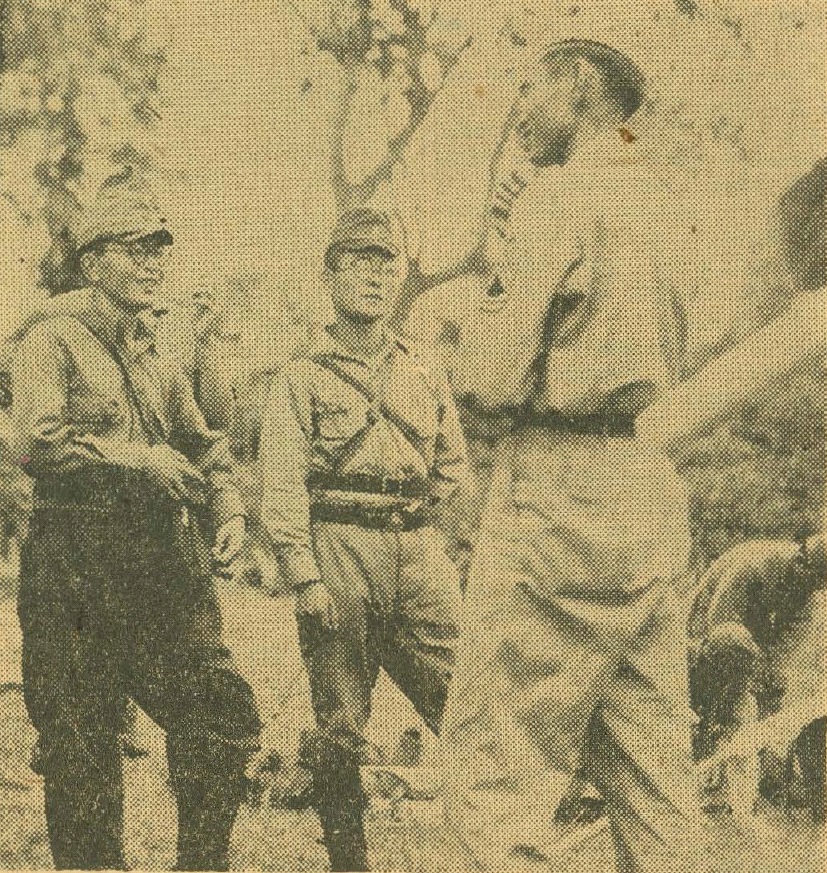

Below: Later surrender photos showing the

mountain path (background) widening into a road (foreground)

as described by Lt. Kumai.

This must be at the river crossing at Tinaan.

Behind the cameramen would be the river.

From this point the Japanese emissaries would then take the "road-along-the-river" to Daja.

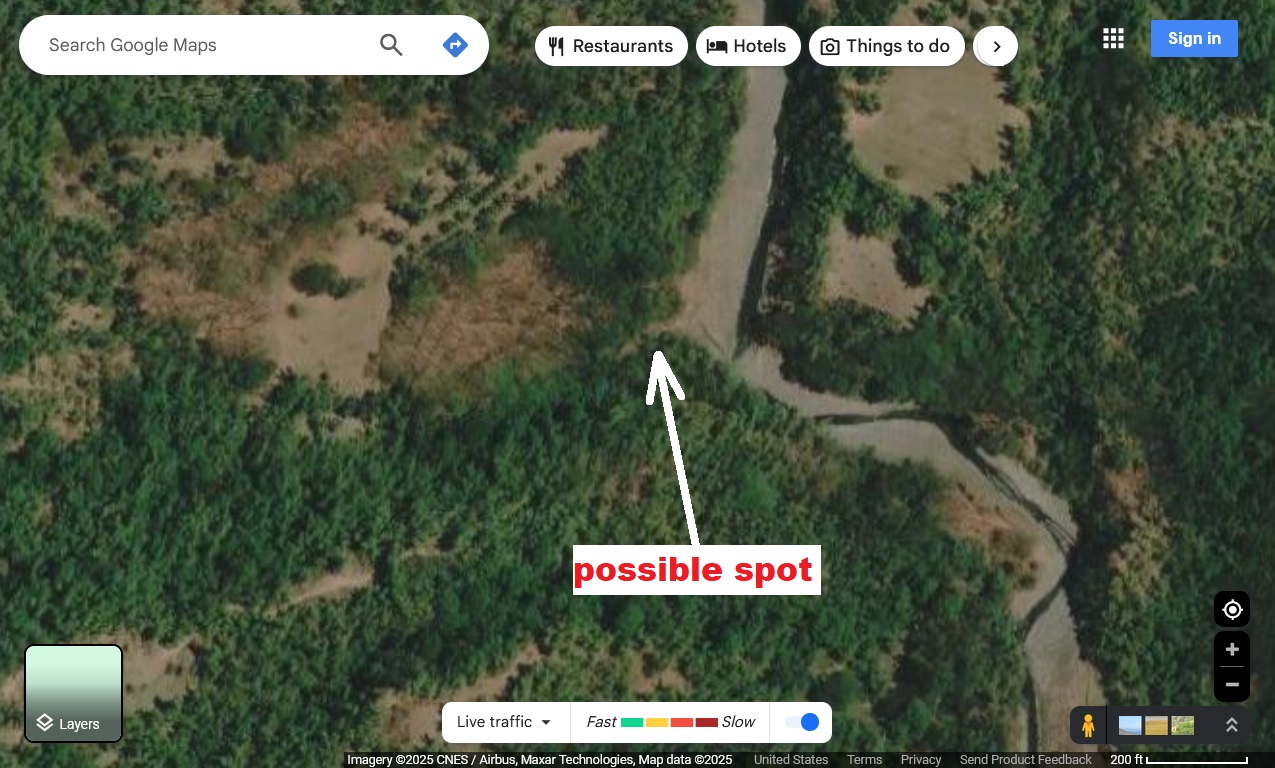

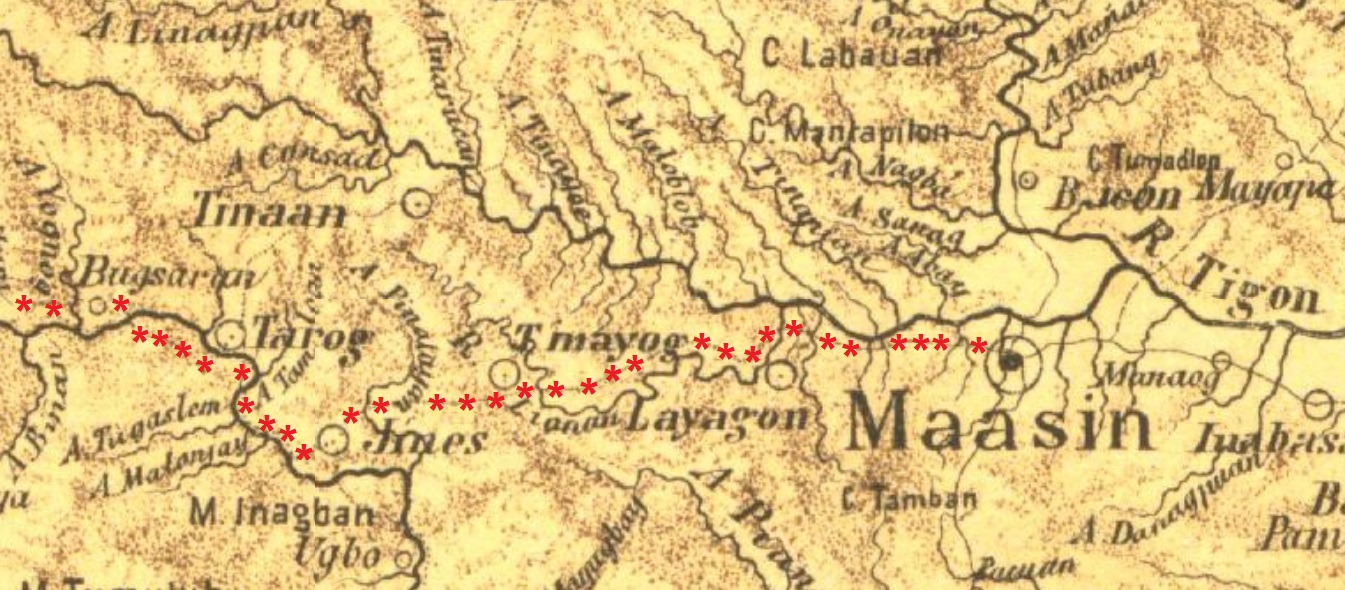

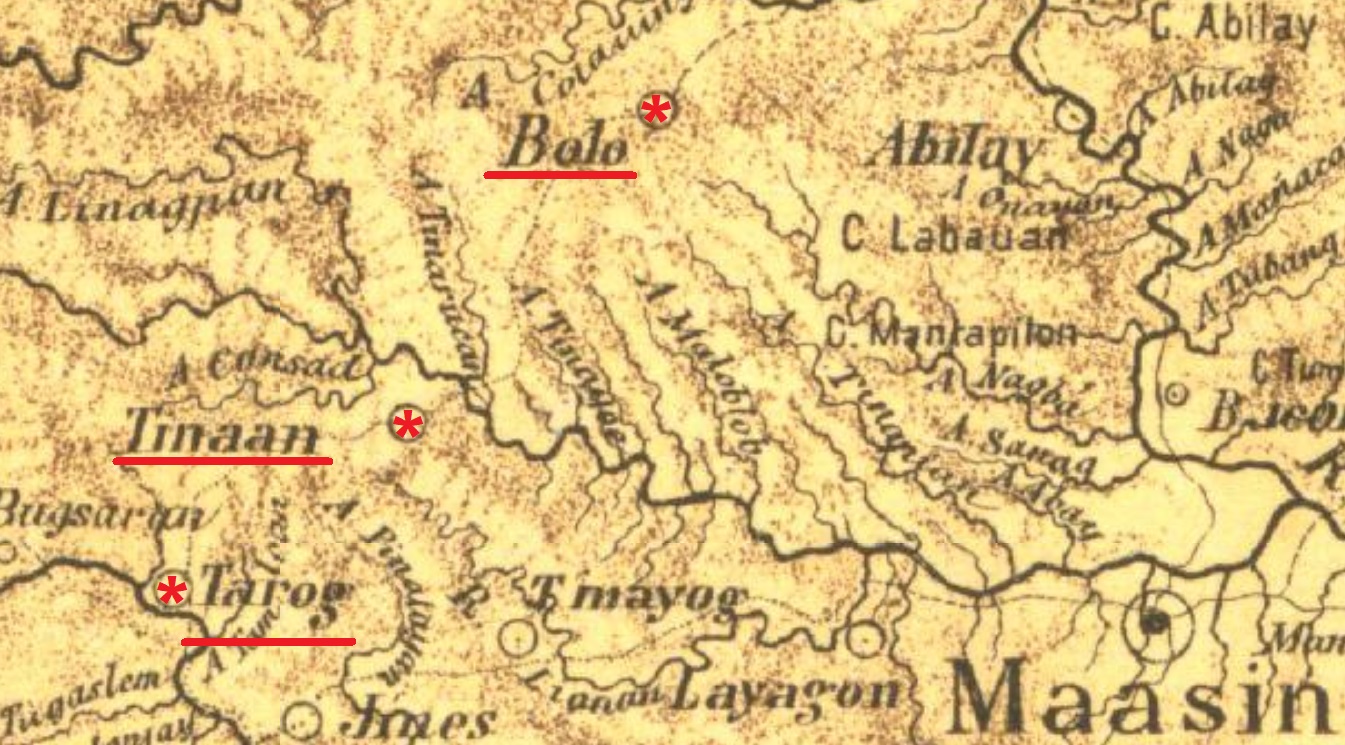

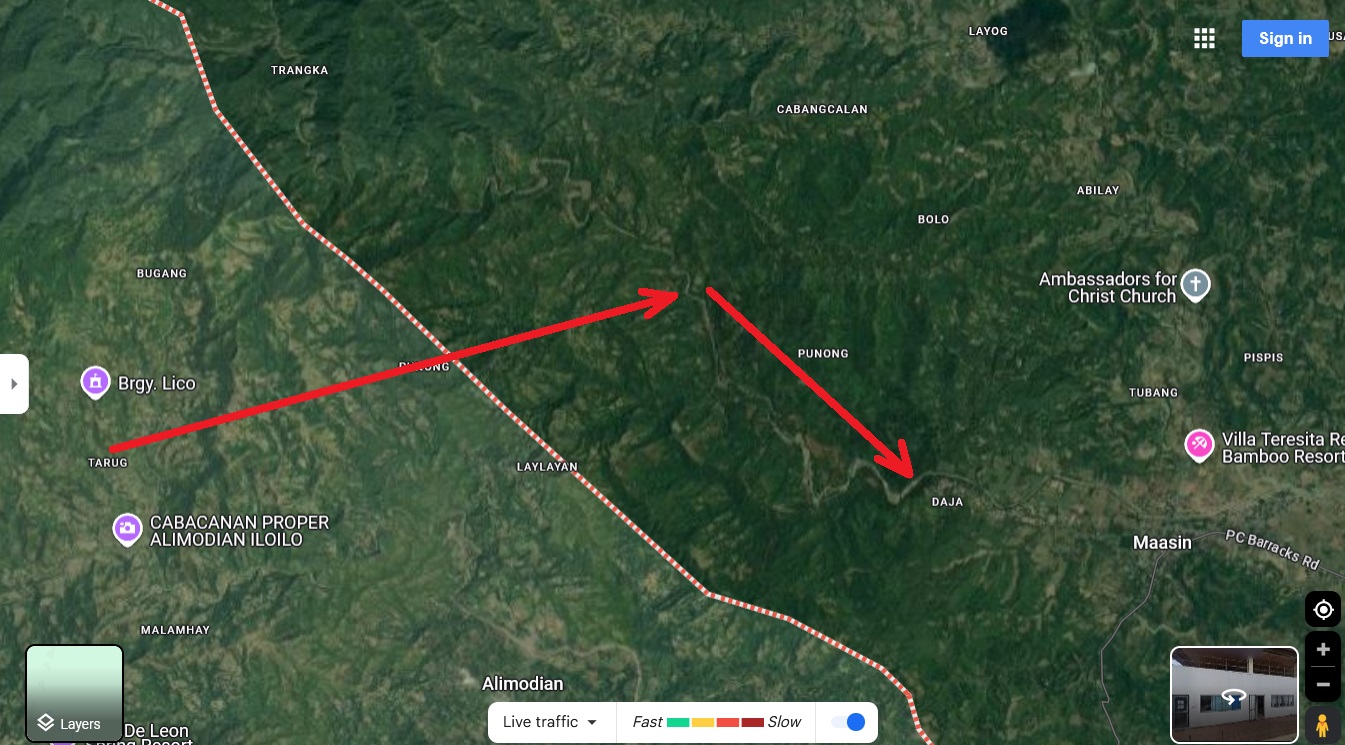

POSSIBLE EXACT SPOT AT THE RIVER

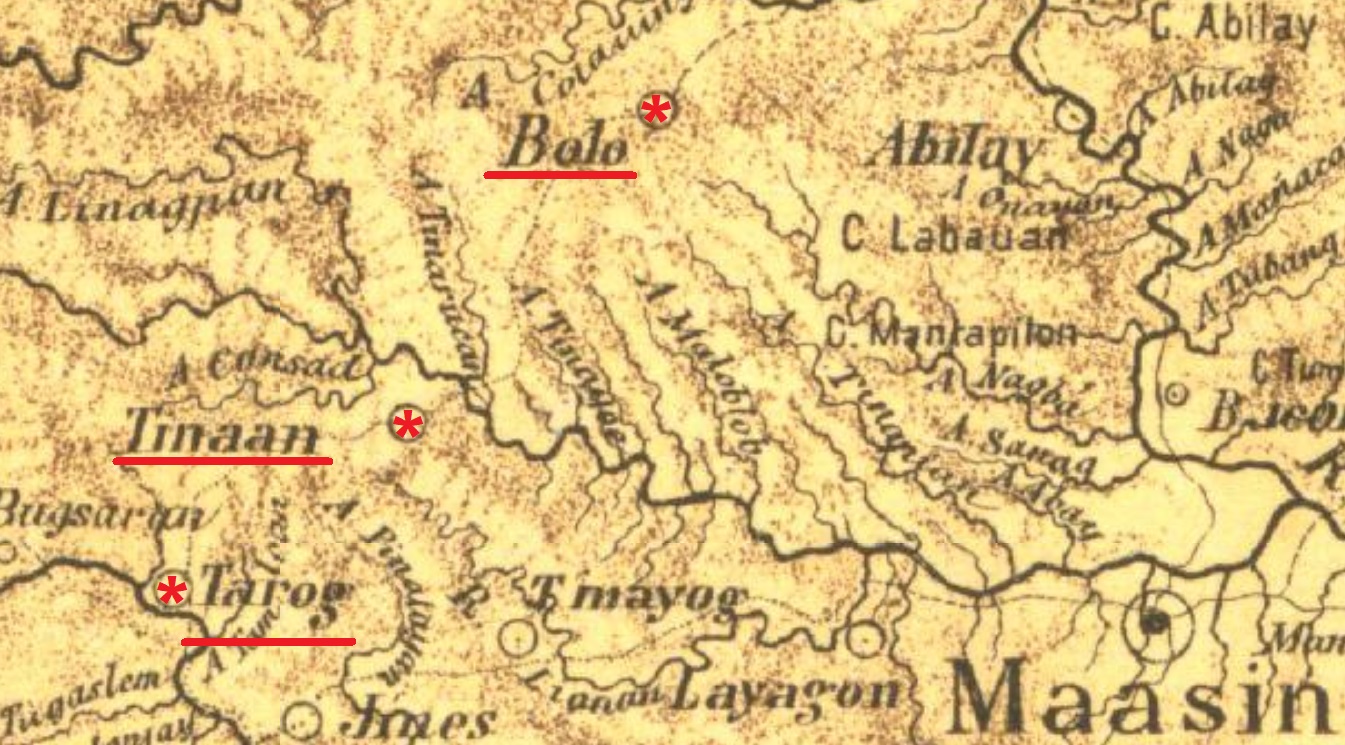

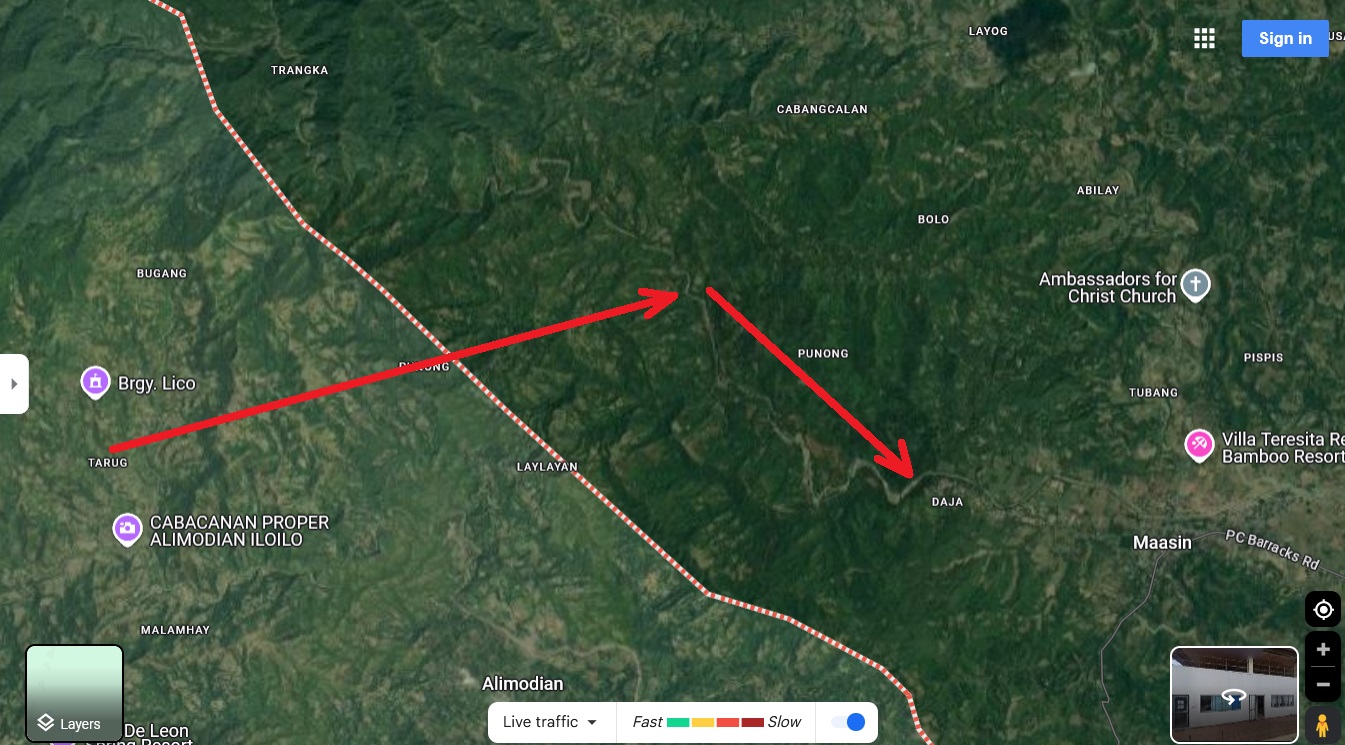

The old map shows that Tinaan was between Tarog and Bolo

and that after Tinaan was the river where they switched directions.

The current map shows only Tarog and Bolo, no Tinaan. However, using Tarog, Bolo, the river, and Daja as guide, we can still draw the path of the Japanese emissaries (and the later surrenderees) from Tarog to Tinaan to the river then to Daja, as follows.

If we look closely at the area of the river between Tarog and Bolo, and look for a possible spot where the trail becomes a road-along-the-river, this would be it.

Take note that the trail (see photo below), from the bottom, as it goes up the hill, is bending to the left, and is not a straight line. The possible spot shown by the satellite photo above is consistent with this feature.

Take note also that Kumai only said that the trail widened into a road, he didn't say that they took a turn onto a road. As this photo below shows, the widening of the path happened before the river. Afterwards, if we look at the satellite photo above, the right side of the river gradually curved to the right.

SGT. HUBBARD SPOTS THE JAPANESE EMISSARIES

AS THEY COME DOWN THE MOUNTAIN TRAIL

AT THE RIVER AT TINAAN

THEN ACCOMPANIES THEM TO DAJA, ON THE ROAD ALONG THE RIVER

As we advanced, we were expecting some contact from the US forces. Suddenly, seven or eight gigantic American soldiers came out of the jungle and surrounded us.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

On August 28 (1945), Alfred Hubbard sighted the first members of the Japanese surrender party as they came down a path from the mountains outside of Maasin.

- 160th Infantry Regiment

Staff Sergeant Alfred E. Hubbard of Elk City, Okla,

lays claim to spotting the white flags borne by the Japs as they wound down a jungle-hidden mountain trail.

Helped Take in Jap Surrender Party

The following story, from Panay in the Philippines, relates how a Caruthersville boy, Pvt. John Boulton, had a part in taking over a party of Japs on Panay Island on August 28, after the general Jap surrender had been negotiated:

Six Infantrymen from the Third Battalion of the 16th Infantry Regiment (160th Infantry Regiment) were on duty at the observation post from which a column of Jap "surrender" emissaries were first sighted on August 28 west of Maasin, Panay.

Staff Sergeant Alfred E. Hubbard of Elk City, Okla,

lays claim to spotting the white flags borne by the Japs as they wound down a jungle-hidden mountain trail.

With him were

Pfc. Anthony Thome, Avon, Ohio;

Pvt. Sam Hutton, Warsaw, Florida;

Pvt. Rudolph Duir, Mosinee, Wisconsin;

Pvt. James Haynie, Ashville, North Carolina; and

Pvt. John Boulton, Caruthersville, Missouri.

|

With a smile on his face, a gentle-looking officer of around 34 or 35 years of age told me that they had come to meet us. He was wearing the insignia of a major. The Major walked cheerfully along with me, as if he were escorting a group of children.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

Below: Later surrender photos showing

heavy foliage on both sides of the mountain trail which supports Staff Sgt. Hubbard's description that the mountain trail was jungle-hidden. The mountain path (background) widening into a road (foreground) would match Lt. Kumai's description of the river crossing at Tinaan. If so, then this photo must be the exact perspective of Sgt. Hubbard when he met the Japanese emissaries on Aug. 28, 1945.

Another later surrender photo, a little forward into the mountain trail,

showing

heavy foliage on both sides of the mountain trail,

which supports Staff Sgt. Hubbard's description that the mountain trail was jungle-hidden.

CAPT. ELISEO D. RIO AT THE RIVER AT TINAAN TO MEET JAPANESE EMISSARIES

A week later (after deciding to drop leaflets), the Americans brought to Panay two civilian Japanese envoys who were among those sent by the Japanese government from Tokyo for the sole purpose of convincing the Japanese soldiers still holding out and surrender.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Early one morning, the Island Commander and two other Americans, one being the Japanese-speaking sergeant who had spoken to the enemy remnants, arrived at the forward command post with the two Japanese envoys and were met by Major Gelveson, the 1st Battalion Commander. They again had with them a set of sound equipment. A party, similar to that which accompanied the sergeant the last time, was formed to escort them. Again, I joined the group as observer. The American Island Commander, together with his officer companion, chose to remain and await developments at the command post with the Battalion Commander .

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

When we got to the site, the sound equipment was installed in almost the same spot as before. When all was set, one of the envoys started to talk through the microphone.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Shortly, three men, one waving a white flag came out on the open trail and stopped about two hundred yards away when they saw us down the trail.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

It suddenly occurred to me that some trigger-happy soldier might be unable to restrain himself from shooting at the emerging enemy and spoil everything. I immediately ran up to the Japanese envoys and requested to say something over the sound system. "Attention, everybody," I was almost shouting into the microphone, "this is Captain Rio speaking. Hold your fire. I repeat, hold your fire. That's an order."

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

The envoy resumed talking over the sound system and the three enemy soldiers continued down the trail. As they came nearer, I saw that two of them were officers. The two envoys stood up and the two groups bowed to each other. The American sergeant joined the Japanese as they went into a discussion while I stood a short distance away.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Later, the sergeant came and told me that one of the Japanese officers, a Lieutenant Colonel, was the overall commander of the enemy left on Panay. He had agreed to go back with us to the forward command post to talk with the Island Commander about their surrender.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

JAPANESE EMISSARIES FINALLY ARRIVE AT DAJA

WHILE ON THE ROAD ALONG THE RIVER

As we moved along the river, the jungle came to an abrupt end and the surroundings suddenly became bright. We were at Daja, the reservoir of Iloilo City’s water supply.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The Japanese did emerge at Daja on the "road-along-the-river" as this photo shows.

They first took this "road-along-the-river" at Tinaan.

Original caption: "The advance surrender party.

This group responded to our drop message on the Japanese surrender,

and came down to learn the terms imposed by Colonel R. G. Stanton, commanding 160th Infantry."

PHOTO OP AT DAJA

Immediately, a dozen news cameras positioned in front of us started to roll. Some American soldiers who surrounded us also clicked the shutters of their cameras. The extraordinary scene that all of a sudden materialized took us all aback. All the American soldiers before us were full of joy and the scene was like that of a festival.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

from left to right, Lieut. Larson, Lieut. Jacobs, Lieut. Sadayoshi Ishikawa, Capt. Kaneyuki Koike and T-Sgt. Terno Odow,

during the surrender negotiations on August 28, 1945 in Maasin, Iloilo. In the background are Japanese soldiers who acted as guards for the Japanese surrender negotiation delegation.

|

RIDE FROM DAJA TO MAASIN CHURCHYARD

Our escorting NCO platoon stood by while the four of us – Captain Koike, 1st Lieutenant Ishikawa, I, and the interpreter Sergeant Matsuzaki – were placed on jeeps. I rode with a battalion commander with a platoon of US soldiers guarding our front and back.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

Our jeeps ran through the forest, and in about five minutes, we could see houses of local residents. Citizens who recognized us came rushing towards the vehicles, following us while shouting all sorts of curses in anger – ‘bakayaro,’ ‘dorobo’ (stupid, thief). Some raised their fists, some mimicked beheading with their hands, and a raging crowd surrounded us.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The jeering reached its height as our jeeps arrived at Maasin plaza.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

At an open space of about 150 square meters, heavy machine guns were set at all directions while around a battalion of soldiers were on strict watch. As if waiting for a theatrical performance around the plaza, hundreds of local people stayed for the start of the meeting between the Japanese Army emissaries and the representatives of American forces.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

AT THE NEGOTIATION TABLE

After the four of us were body-checked, the battalion commander escorted us to a table positioned at the center of the plaza.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

At the center of the table sat a dignified colonel of around 45 or 46 years old. Along with three or four more young officers, a shrewd-looking young Lieutenant Colonel sat on his left and a major of around 50 years of age sat on his right.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

At the right side of the table, from the far end:

the Major (mostly hidden), Col. Stanton, Lieut. Col. Marr, Tech. Sgt. Terno Odow (translator).

At the left side of the table, not necessarily in the following order, presumably are:

Captain Koike, Lt. Kumai, Lt. Ishikawa, Sgt. Matsuzaki (interpreter).

Lt. Ishikawa appears to be the third from left.

At the forward command post, a rectangular table was set up for

the talks. The American Island Commander sat in the middle of one

side. The 1st Battalion Commander, whom the Regimental

Commander designated to represent him, sat to his left, while I sat

next to the Battalion Commander. At the Island Commander's right

sat the American staff officer beside whom was the American sergeant

acting as interpreter.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Opposite the Island Commander at the other side of the table sat the Japanese Lieutenant Colonel, with the two envoys sitting side-by-side to his left and the other Japanese officer to his right. Two enlisted-men clerks from the 1st Battalion Headquarters were seated, one at each end of the table, to take notes of the proceedings.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

THE HONOR COMPANY

Behind them stood the bearers of the US and the regimental flags while around 20 colossal soldiers surrounded them in a half circle.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

Pvt. Richard J. Dagenhart, scout, 1911 M street N.E., Washington D. C., was a member of the "honor company" of the 40th Infantry Division which provided a guard at preliminary negotiations August 28 for the surrender of 1,700 Japanese troops and civilians on Panay Island.

Private Edwin Johns, rifleman, of

Juneau, Alaska, was a member of

the "Honor Company" of the 40th

Infantry Division which provided

a guard at preliminary negotiations

August 28 for surrender of 1700

Japanese troops and civilians on Panay Island.

The "honor company" was Company I of the 160th Infantry Regiment. Commanded by Lt. Norman F. Powell, 9031 Fort Hamilton Pkway, Brooklyn, N.Y., Company I numbers among its heroes Congressional Medal of Honor winner Lt. John Sjogren of Rockford, Mich.

The meeting took place in the historic Maasin churchyard, where, three years ago, an American-Filipino force laid down its arms when the Japs seized Panay.

|

On the other hand, the honor guard at the Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945 belonged to the

Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon commanded by Lieutenant Herman E. Bulling.

LIEUT. COL. JAMES K. MARR

A meeting was duly effected between the Japanese and Americans.

- 40th Infantry Division

We met Lieutenant Colonel James K. Maar (Lieutenant Colonel James K. Marr), at Maasin on the morning of the 28th

- Lt. Sadayoshi Ishikawa

Only the young Lieutenant Colonel on the US side and myself on the Japanese side attended to the technical details related to the surrender.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

SIMILARITY TO BATAAN

The set-up reminds me of another event, almost three and a half years

ago, when Colonel Berry, the American Commander of the 1st Regular

Division in Bataan, and I sat down in a similar conference with the

Japanese to discuss the surrender of our division. I am moved by the thought

that Colonel Berry would have been very pleased to see me as a participant

in this complete reversal of the humiliation he had to put up with upon the

surrender of Bataan. What adds to my elation is the realization that, while in Bataan

we surrendered after our defeat in a battle, this time the enemy are negotiating for surrender

because they lost the war. Yes, we got knocked down in several of the rounds, but we got up each time to win the bout, finally!

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Having experienced the acceptance of POWs at the capture of Bataan Peninsula, I replied in detail to questions such as the number of Japanese Army members, the number of patients, and weapons at Bocari. As a whole, the talk concluded smoothly, although there were a few points on which we did not agree.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

JAPANESE REQUEST ABOUT FILIPINOS

During the discussion, I pointed out that we were shot at by Filipino soldiers and civilians on the way down to surrender and requested for a guarantee that such behavior would not be repeated in the future. The US side promised they would be responsible for our safety.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The Japanese commanding officer spoke first, pausing often to allow the interpreter to translate what he said and to consult now and then with the envoys beside him. He and his entire troops, he said, would come out of their mountain lair as a single group and surrender at a place designated by the American Commander. He requested. however, that only Americans should compose the unit to receive their surrender. He requested further that the Filipino guerrilla units be pulled out of the mountain areas and all Filipinos including civilians be cleared from the site of the surrender, before they would come down.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Major Ramon Gelveson, the 1st Battalion Commander, and I looked at each other with amazement at the Japanese's requests. I understood then why the Japanese had spurned all our previous demands for their surrender; they were totally adverse to the idea of surrendering to Filipinos or doing so in the presence of Filipinos. Major Gelveson whispered to me that he thought the enemy's requests were indicative of their morbid fear that the Filipinos would tear each one of them apart in their great anger at the countless atrocities the enemy had committed over the years mostly on the non-combatant populace of Panay. To me, however, it was but another expression of the contempt the enemy had for the Filipinos.

They simply could not allow themselves to surrender to a people whom they look upon as their inferior or to be witnessed by these people in their moment of disgrace as they surrender to the Americans.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

"I am not granting any of the requests of the Japanese commander for two reasons," the American Island Commander replied, with the sergeant translating what he said. "First, all the Philippine military units on Panay are integral parts of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East. As such, they are as entitled as any unit of the United States Armed Forces to accept the surrender of the enemy. Second, I shall accept your surrender only if it is offered unconditionally. As the Island Commander, I guarantee that upon your surrender you and your men will be treated in accordance with the provisions of the Articles of Surrender signed in Tokyo on 2 September 1945."

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

The Japanese went into a spirited discussion among themselves.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Finally, the Japanese commander declared, as translated, "Considering the remarks of the American commander, I am surrendering unconditionally the unit of the Japanese Imperial Army that I command to the United States Armed Forces in the Far East. Please instruct us as to the course of action we should take."

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

HUDDLING OVER MAPS

The Island Commander spoke, occasionally pausing and consulting

with the 1st Battalion Commander. "After this meeting, you shall be escorted back to your unit. We shall pull out all our troops from the mountain areas in order that nothing shall stand in the way of your consolidating your men. Then on 1 September, that's the day after tomorrow, your entire unit shall come down to the barrio of Tinaan at the foot of the mountain range, to arrive there not later than 0800 Hours." The Island Commander indicated the location of Tinaan on our operations map, and the Japanese commander noted it down on the map he had with him.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

This photo came together with the other Iloilo surrender photos. The scene matches a description of Eliseo D. Rio that during the surrender negotiations the Americans and Japanese pointed at their maps the location of their agreed meeting place. Lieut. Sadayoshi Ishikawa appears to be second from left. The Japanese-American translator Tech. Sgt. Terno Odow appears to be at far right, in the foreground.

|

PLANS ARE MADE FOR THE FORMAL SURRENDER AT CABATUAN AIRFIELD

In the ensuing conference plans were made to receive the

formal surrender of all Japanese forces on Panay and to

evacuate them from the Mt. Singit and Bucari Areas.

- 40th Infantry Division

For 100 headquarters officers and the rest of the unit, the agreed date of surrender was September 1. The surrender of the Saitô unit was to follow on September 2.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

I also asked for transport vehicles for all the Japanese soldiers secured by the American forces as well as special transport and hospitalization for the patients. To our surprise, they readily accepted these requests without hesitation.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The American then continued, "When you come down, have someone carry at the head of your marching column for identification purposes. We shall have our men waiting to receive you at the Tinaan barrio school grounds, where you will be asked to stack and leave all your arms and ammunition. You will be given a hot breakfast, and at 0900 Hours you will be marched under escort to this place. When you get here, you will be loaded in military trucks and brought to the Cabatuan Airfield, where the formal surrender ceremony shall be held. Do you have any questions?" The Japanese shook his head.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

"What is your present strength?" the Island Commander asked

further."

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

"We are exactly 92 men - 14 officers and 78 enlisted men."

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Having experienced the acceptance of POWs at the capture of Bataan Peninsula, I replied in detail to questions such as the number of Japanese Army members, the number of patients, and weapons at Bocari. As a whole, the talk concluded smoothly, although there were a few points on which we did not agree.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

We ended the meeting with our request to give the surrender instructions to the Saitô unit.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

T/4 ROBERT A. WAY TYPES OUT THE TERMS OF SURRENDER

T/4 Robert A. Way Typed Out Terms Of Jap Surrender With the 40th Infantry Division on Panay, P. I.—T/4 Robert A. Way of Wells, Mich., secretary to the 160th Infantry Regimental Commander, 40th Division, typed out surrender terms for 1800 Japanese troops and civilians on Aug. 28 while Jap emissaries waited nearby.

THE MEETING ENDS

The Island Commander stood up, which was the signal for everyone

around the table to do likewise. He extended his hand to the Japanese

commander across the table and they shook hands with the Japanese

snapping into a smart salute afterwards. The Japanese commander and his companions bowed to the two envoys and promptly left for the mountains with the same squad of soldiers that escorted them when they came down.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

After a round of handshakes among the remaining participants in the conference including the two Japanese envoys the crowd dispersed. The two envoys rode with the Island Commander back to Iloilo City.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

Colonel R.G. Stanton (commanding officer of the 160th Infantry Regiment) signed the instrument of surrender on the US side, and Captain Koike on the Japanese side. Just when the signing was finished, it suddenly became calm. With the command, ‘Ten hut!’ Colonel Stanton and the others all stood up and saluted. As we turned together and saluted, we saw a noble Major General of around 50 years of age, who had a face like a young boy, followed by his staff. He was smiling contentedly and repeatedly returned our salute. A Japanese-American interpreter standing close to me whispered it was the 40th Division Commander, Major General Rapp Brush.*

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir:

*This must be the ending of the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945 that Kumai had mistakenly placed here.

Kumai had mistaken Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis (a two-star admiral) for Maj. Gen. Rapp Brush (a two-star general).

(See surrender signing ceremony)

Major General Rapp Brush had already been replaced by Brig. General Donald J. Myers as commander of the 40th Infantry Division a month earlier, in July 1945, (Brush returned to the U.S.), so Gen. Brush could not have been present anymore at this Maasin meeting, and Myers was only a one-star brig. general, and from his photos, Gen. Myers wasn't young looking.

On the other hand, at the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2 1945, there was somebody there who fitted the bill, a young looking two-star officer, in the person of Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis, who had arrived only the day before, September 1, 1945, aboard his flagship USS Estes, so Davis could have been only at the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield and not in the Maasin meeting in August.

During the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield, Rear Admiral Ralph O. Davis can be seen in the photos as being seated at the side. Most likely, after the signing, when he stood up, that's when "ten hut" was called.

Rear Admiral Davis and his 13th Amphibious Group were in Iloilo to transfer the 40th Infantry Division to Korea for occupation. This transfer began with the ship LSD Carter Hall being the first vessel to depart Iloilo five days later, on September 7, 1945, with the advance party of the 40th Infantry Division and elements of the 532nd EB & SR. The rest of the division followed on other transport ships. Control of the Cabatuan Airfield POW camp was turned over to the 658th tractor battalion that same day, September 7, 1945

At the surrender signing ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945, the instrument of surrender was signed by the overall Japanese commander Lieut. Col. Ryoichi Tozuka for the Japanese, and by the 160th US Infantry Regiment commander Col. Raymond G. Stanton for the Americans and Filipinos. Protocol dictates that a surrender be received by an officer of about the same rank and position, and so Col. Stanton was designated to receive even though his superiors were also present.

See also: Japanese Surrender Signing Ceremony at Cabatuan Airfield on September 2, 1945

|

JAPANESE EMISSARIES RETURN TO BOCARI

The Japanese commander and his companions bowed to the two envoys and promptly left for the mountains with the same squad of soldiers that escorted them when they came down.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

On the way back, the people along the road kept shouting but I noticed their faces were full of joy as they must have known of the surrender of the Japanese Army. On our way back to the mountains, the US observation plane saw us off from above but we did not hear any gunshots.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

We reached the Bocari headquarters around 3 p.m. Colonel Tozuka and other commanders were eagerly waiting for our return.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

The three of us immediately reported to them the details of the meeting with the American forces and the disturbances made by the local people along the road on our way to and from the surrender site. We pointed out that the US forces were kind and courteous, more than we had expected. Alcoholic beverages made from corn were offered for celebration. The commanders immediately left without touching them, however, to tell their men of the developments. A joyous and relieved atmosphere soon filled the whole mountain of Bocari and the soldiers of the headquarters were excited like children going on an excursion. The officers and men of Panay were so exhausted that they could not afford to grieve for the defeat of their country.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

CAPT. ELISEO D. RIO TO ORGANIZE HONOR COMPANY

FOR THE FORMAL SURRENDER, OR THE SURRENDER SIGNING CEREMONY

AT CABATUAN AIRFIELD

Having been called away on official business, the commander of

the 52nd Infantry Regiment designated Major Gelveson, 1st Battalion

Commander, as his representative in the surrender ceremony and asked

him to take charge of all arrangements attendant to it. In turn, Major Gelveson requested me to organize and command a rifle company, using men from his battalion, which was to act as the honor guard during the ceremony.

- Capt. Eliseo D. Rio

CABATUAN AIRFIELD POW CAMP.

AMERICANS BUILD POW CAMP AT CABATUAN AIRFIELD

TO ACCOMMODATE THE SURRENDERING JAPANESE

We waited a couple of days, until we got a stockade built for five hundred troops.

- Lt. Herman E. Bulling, I&R Platoon 40th Infantry Division (Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon)

Tents were built in the 200 square-meter POW camp surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. US soldiers were on duty in the watchtowers.

- Lt. Toshimi Kumai Section 10.1

|