Marker at Sitio Suyac, Maasin, Iloilo Photo courtesy of NGO LOOB The marker reads: Monument for Peace and Friendship of the Philippines and Japan ... To the Memory of the Lost Lives and for Peace and Friendship in the Future. |

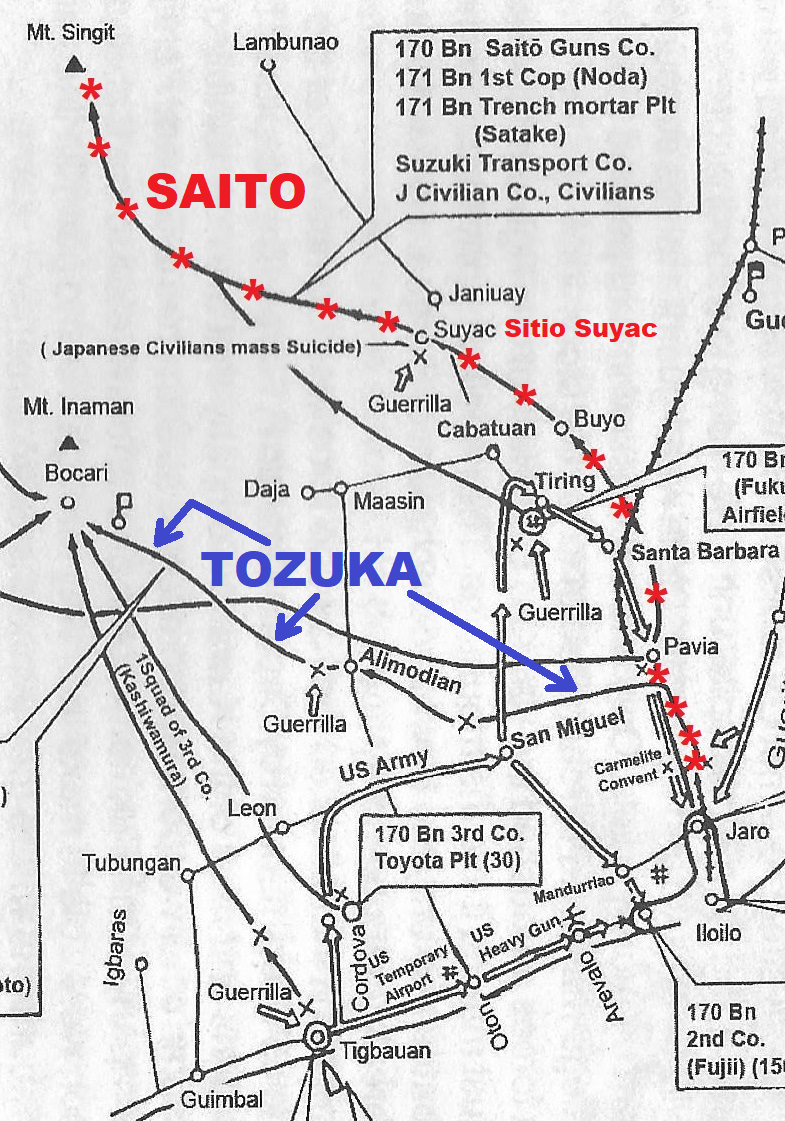

The Saitô forces, which had come to be separated from the main force, made a quick advance toward Pavia after engaging in a fierce combat.

In the early morning of March 19,* they had crossed the Jaro River behind the town hall of Pavia. They reached a coconut grove about half a kilometer northeast of the town where they stayed to wait for the rest of the group.

| *This should be March 20, 1945. |

Under the command of Captain Saitô then were 150 men of the machine-gun force, 130 of the Suzuki transport company, 180 the Noda company of the Tanabe unit, 50 of the Ika Hôjin company, 30 of the remaining 102nd Division Force, and 200 Hôjin women and children. However, patients of the Army Hospital and some soldier dropouts were also left behind.

Captain Saitô dispatched a messenger squad to inform headquarters of their whereabouts; but upon meeting with enemy tanks, the squad returned without making contact.

Taking over command from the wounded Captain Saitô, 1st Lieutenant Yamamoto led the forces and the Hôjin.

They left the spot around noon, and by around 1 p.m., they reached a coconut grove about a kilometer and a half north of Pavia where they rested until it was dark.

They started again at 8 p.m., passing three to four kilometers north of the town of Santa Barbara, and reached the heavily wooded area of Barrio Buyo, four kilometers east of the town of Cabatuan. They hid there the next day and resumed their movement at night. On the way, they frequently had to cross a road used by US military trucks.

|

The Saito Forces, which included the Japanese civilians,

had become separated from the main force of Lieut. Col. Tozuka.

Saito proceeded to Mt. Bongbong / Mt. Singit while Tozuka followed the original plan to Bocari. Along his route, Saito passed by Sitio Suyac, below Janiuay, and it was at this sitio that the Japanese civilians committed suicide.

Ishikawa map showing the separation (labelled "contact broken") of the Saito Advance Guard from the Tozuka Main Force

|

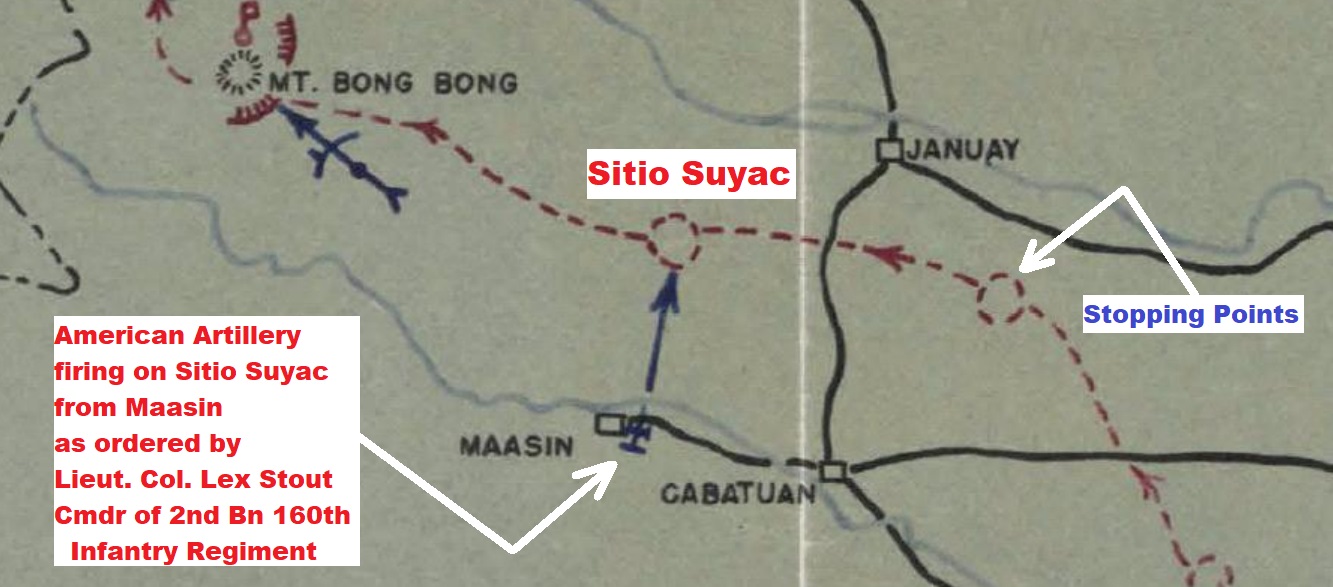

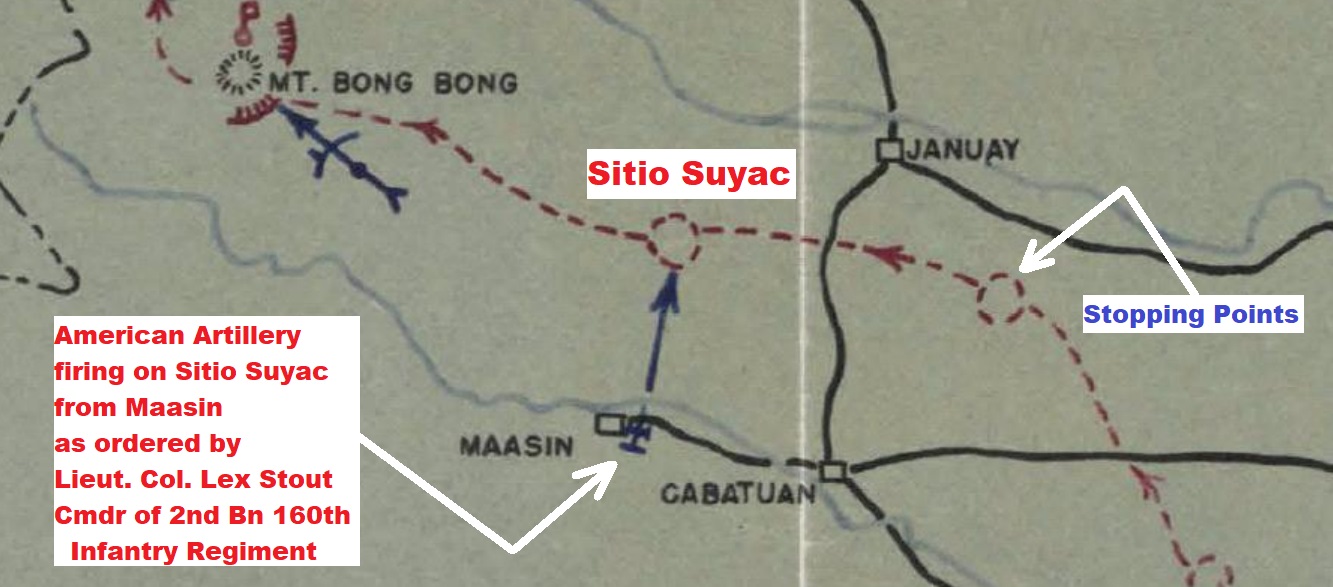

Around 5 a.m. of March 21, they entered a mountainous area of Suyac of Barrio Tigbauan Road, part of Maasin, and about four and a half kilometers southwest of the town of Janiuay. It was in this forested mountainside with a river running below where they decided to take a rest until it was dark once more.

Using a straight line, the distance of Suyac from Pavia was only 25 kilometers. However, it seemed longer then since it was difficult and dangerous to move at night. The elderly Hôjin men, women and children were physically and mentally exhausted. In the beginning, they each had large packs on their backs full of necessities and carried other possessions in both hands. Some even had children with them. In time, they were tired and dragged themselves as they trailed after the soldiers’ lead. Some soldiers helped carry the children or their bags. Gradually, though, the bags were left behind. Since some soldiers were still tense from their skirmishes, they warned the Hôjin, ‘Do not let the children cry. Their sounds will tell the enemy where we are. What are the parents doing?’ ‘Kill the child!’ When children started crying, therefore, their mothers scolded them like mad. Some desperately covered the children’s mouths with their hands to suppress the noise. In this overwrought atmosphere, Kichisaburo Maruyama of the Iloilo Consulate strove to protect the Hôjin by mediating between them and the soldiers.

The net of the guerrilla siege was gradually closing in.

In addition, at around 5:00 p.m., the US artillery started a rigorous bombardment of the area from nearby Maasin. With the explosions, the assembled Japanese fell into disarray. The Hôjin, in particular, had lost whatever spirit and energy they had left.

American Artillery firing on Sitio Suyac from Maasin

|

Sometime later that night of the 21st, around 40 Hôjin got together. The principal of the Iloilo Japanese School Kayamori spoke out what was in his mind, ‘I feel that we should not be a further burden to the soldiers. Let us die here.’ Others thought it better to live even if humiliated. Nevertheless, they sang their farewell song in unison – Umi Yukaba (If I Go to Sea) – and bowed in the direction of the Imperial Palace. Some killed themselves with pistols and hand grenades. Failing to kill themselves, some mothers in agony sought the help of passing straggling and wounded soldiers who used bayonets or hand grenades.

Some of those soldiers finally caught up with the Saitô force and told the others of the mass suicide (jiketsu). The news spread among the soldiers and finally reached Captain Saitô. He was shocked; he ordered Corporal Katsuyoshi Yamaguchi of the headquarters wire communications unit and several other soldiers to confirm the news of the Hôjin suicides. Corporal Yamaguchi and others dared to go back through guerrilla lines and reached the place of the mass suicides at Suyac in the early morning of the 23rd. They found and identified the bodies of Principal Kayamori, who had a pistol shot on his right temple, and many corpses of those who had killed themselves. However, as guerrillas started to attack, they had to leave without being able to collect the remains.

28. Sketch of the mass suicide site (night of 21 March 1945) (based on interviews with local residents) |

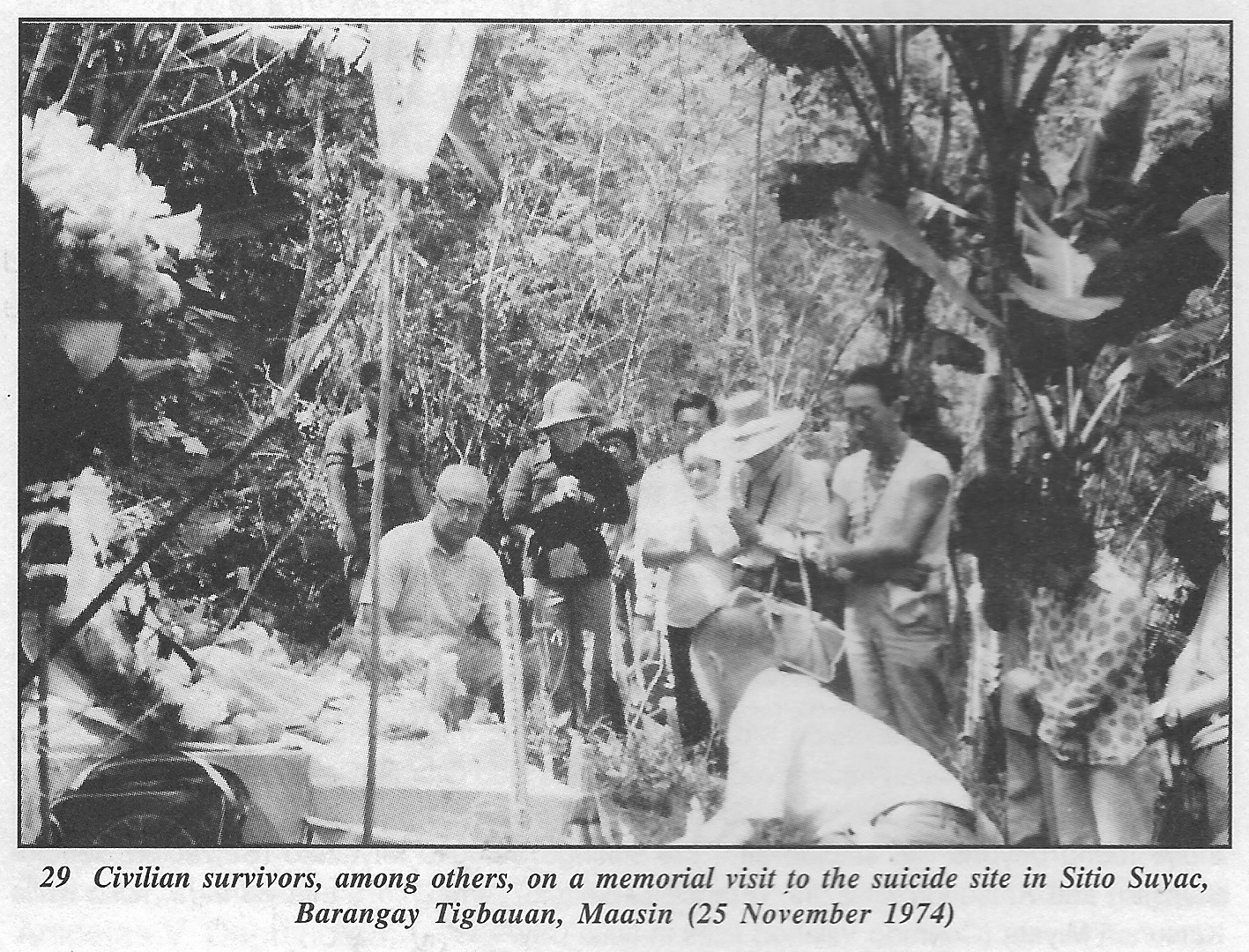

29. Civilian survivors, among others, on a memorial visit to the suicide site in Sitio Suyac, Barangay Tigbauan, Maasin (25 November 1974) |

Later research made it clear that around 40 elderly men, women and children perished here, although only 22 identities have been confirmed.

Section 8.3

PARTIAL LIST OF JAPANESE CIVILIANS IN MASS SUICIDE

(21 March 1945, at Suyac, Barangay Tigbauan, Maasin, Iloilo)

| NAME | APPROX. AGE | SEX | REMARKS |

| 1. Kayamori, Isao | 55 | M | headmaster or principal of the Iloilo Japanese School |

| 2. Kayamori, Ryoko | 8 | F | youngest daughter of Kayamori |

| 3. Hatade, Mieko | 28 | M |

teacher at the Japanese school, daughter of Kayamori, married to Hatade |

| 4. Hatade, Keiko | 4 | F |

grandchild of Kayamori, daughter of the Hatades |

| 5. Hatade, Syuichi | 2 | M |

grandchild of Kayamori, son of the Hatades |

| 6. Takaezu, Izo | 55 | M |

chief of the fishing guild; prewar chief of the Japanese Association |

| 7. Miyata, Motokichi | 53 | M | elder brother of Yosokichi Miyata |

| 8. Miyata, Machiko | 33 | M |

wife of Yosokichi Miyata, owner of Tokiwa restaurant |

| 9. Miyata, Chieko | 3 | F | youngest daughter of Yosokichi Miyata |

| 10. Hanamasuya, Hisako | 33 | F |

head of Japanese Ladies' Society (husband died of illness in the mountains) |

| 11. Hanamasuya, Yukiko | 11 | F | daughter of the Hanamasuyas |

| 12. Hanamasuya, Kuniaki | 8 | M | son of the Hanamasuyas |

| 13. Hanamasuya, Michiko | 4 | F | daughter of the Hanamasuyas |

| 14. Hanamasuya, Hiroshi | 2 | M | youngest son of the Hanamasuyas |

| 15. Kimoto, Mr. | 54 | M | owner of candy store at Iloilo City |

| 16. Kimoto, Mrs. | 50 | F | wife of Kimoto |

| 17. Kimoto, Ms. | 3 | F | second daughter of the Kimotos |

| 18. Hirano, Mrs. | F | wife of carpenter, Mr. Hirano | |

| 19. Hirano, Yoko | 8 | F | daughter of the Hiranos |

| 20. Kamo, Mrs. | F |

wife of barbershop owner; (husband was able to return to Japan) |

|

| 21. Kamo, Kazuko | 11 | F | daughter of the Kamos |

| 22. Kamo, Ms. | 8 | F | second daughter of the Kamos |

| 23. Shirakawa, Mrs. | 33 | F | wife and mother |

| 24. Shirakawa, Yoko | 11 | F | eldest daughter of the Shirakawas |

| 25. Shirakawa, Masaharu | 8 | M | son of the Shirakawas |

| 26. Shirakawa, Masatomi | 3 | M | son of the Shirakawas |

| 27. Inagaki, Mr. [Matsuji] | 38 | M | Prewar carpenter, owner of Tokyo Bazar |

| 28. Sato, Mr. | 50 | M | carpenter |

| 29. Naka, Akio | M | died by bombardment in Suyac | |

| 30. Kawakami, Hatsuyo | 29 | F |

mother of Salvacion Moreno, wife of Tokumatsu Kawakami who returned to Japan but has since died |

| 31. Kawakami, Mr. | baby | M | baby son of the Kawakamis |

| 32. Kawakami, Kiku | F | from Okinawa prefecture | |

| 33. Mrs. | F | younger sister of Kiku Kawakami | |

| 34. Toma, Kamekichi | M |

Presumed to have died here; identified by son Seizo who survived (Pablo Delgado) |

|

| 35. Toma, Ms. | F |

daughter of Toma presumed to have died here |

|

| 36. Toma, Mr. | M |

son of Toma; presumed to have died here |

|

| 37. Fujimoto, Mr. | M |

husband; presumed to have died here |

|

| 38. Fujimoto, Mrs. | F |

wife; presumed to have died here |

|

| 39. Matsuura, Takashi | M |

employee of Ishihara Sangyo; presumed to have died here |

The Mud and Blood in the Philippines: Anti-Guerilla Warfare on Panay Island

Earlier on March 19, there had been about 200 imin, 50 gunzoku, some patients and personnel evacuated from the army hospital who had followed the advance guards that were separated from the main group (Kumai 1977, 174-179).

By the evening of March 21, they trailed behind the soldiers who inadvertently deviated from the master plan; they crossed the river at Pavia and moved northwest through Sta. Barbara into the Cabatuan- Maasin area south of Janiuay. Guerrillas were closing in and American artillery fired around them from Maasin. Burdened with heavy packs, it was difficult and dangerous for them to carry and guide the children while evading tracking guerrilla fire and volleys from incoming American tanks. Feeling vulnerable and helpless with numerous casualties along the way, some were even fearful of the wounded soldiers among them who threatened to still the hungry babies lest their howls reveal their position. Without food and water, disheartened and fraught with physical, mental and emotional fatigue in the dead of night of March 21, a desperate group elderly imin, women and children among them succumbed to selfdetermination or mass suicide (shudan jiketsu).25

| 25 Alternative names have been commonly used to refer to the suicide site in Maasin, between these interior towns of Iloilo (e.g., Suyac and Tuy-an). The location has been verified to be at the edge of the village of Tigbauan adjacent to that of Tuy-an. |

Kocho sensei Kayamori and association president Takaezu were with said group. On this third night of their travails, both leaders observed that the group should no longer be a further burden to the soldiers and others who kept up with them, and that they should all die in the forested hillside shelter where they rested. Anticipating the worst, some agreed that dying was a better option than to live with the humiliation of capture and torture, especially by guerrillas. Softly singing the Kimigayo as farewell, they bowed towards the imperial palace before retiring. At around midnight, the injured soldiers threw down the remaining three grenades on prone bodies at rest. Kayamori and Takaezu used the only two pistols on themselves and the wounded soldiers used bayonets to end their own lives. Some women covered the young from blasts that shattered their own bodies. Those who did not die immediately begged others to end their misery; passing straggling soldiers complied with bayonets and grenades.

Only 22 of at least 40 Japanese who perished here have been identified, including members of the Hanamasuya, Hirano, Kawakami, Miyata, Oshiro and Toma families (Kumai 1977, 175-176). Tami Oshiro and Chiyo Saki were among four adult women from Okinawa who lived to speak of the Maasin suicide.26 Oshiro remained to be with her mother-in-law who could not walk anymore and decided to die with other family members. Saki, then 29 years, claimed that there were about 120 in the group that had been at the suicide site, including a few elderly men and two wounded soldiers. Hence, the total may be understated. But then it may have been that only the elderly and those women with children decided to stay and die. At any rate, this little-known event imparts a certain distinction on the nikkeijin who trace their lineage to the fatalities and survivors of this tragedy in Panay.

| 26 Their testimonies on this event are in Japanese sources: the NNN 1983 television documentary and the Yomiuri 1983 volume, 136-173. One other adult survivor was the second daughter of Haruyoshi and Moyoe Hirano. |

- Ma. Luisa E. Mabunay

Tracing the Roots of the Nikkeijin of Panay, Philippines

When the Japanese soldiers evacuated Iloilo, they forced some four hundred Japanese civilians to accompany them. Since we couldn't locate the soldiers, we did not know this until March 23.

Nine of seventy-one Japanese civilians who escaped a massacre by their·own troops told their story when they were treated by our medics.

Two of the survivors, both middle-aged women, who had been bayoneted testified that they were stabbed in their sleep. They had not been allowed to sleep for three nights and were kept marching all of the time.

On the fourth night when they were allowed to lie down, the Japanese soldiers killed sixty-two men, women and children.

They were discovered the next morning by one of our patrols who sent word for the medics.

Harry Robinson, Milton Ketchum and Ray Brown, a chaplain's assistant, journied six miles over the narrow carabao trail into the mountains to their aid.

Half-naked bodies of men, women and children of all ages were sprawled over the grassy knoll.

An expectant mother was slashed from her throat down and her unborn infant was on the ground beside her.

A father, who had apparently tried to shield his son lay lifeless over the dead child.

A middle-aged man had six half-smoked cigarets sticking out of his mouth, while another still clung to his broken clay pipe.

Near one woman's hand was a small wooden grave marker with the date, May 8, 1942 inscribed on one side.

There was no order to the scene -- except perhaps the systematic way they had been killed. Sinall bits of cloth-and other personal articles and worthless Japanese yen were strung around the dead. Posted on a tree and signed by a Japanese official were these words in Japanese, Fifty people will die here under this tree."

"That place will always stick with me, no matter what," said Ketchum, when he had returned with the wounded to the market place where Doctor Wesley Logan, Fred Jensen and R. C. Hall waited to treat them.

Lt. Colonel Stout* received reports that the Japanese were on the hill and had sent out two platoons the night before the civilians were found.

"At that time," he said, "we did not know there were any civilians with them. I decided to throw in an artillery barrage and hold off an attack until morning."

|

*Lieut. Col. Lex M. Stout was the battalion commander of the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment.

When the Americans landed in Tigbauan on March 18, 1945, the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment, upon landing that morning of March 18 1945, immediately raced to Cabatuan in a mechanized blitzkrieg lightning swoop, by way of Cordova, Leon and San Miguel, to liberate Cabatuan Airfield and Cabatuan, arriving in Cabatuan that night, at midnight. From Cabatuan, they sent patrols chasing the Japs in all directions, whenever they were reported by natives. See Blietzkrieg to Cabatuan by the 2nd Battalion 160th Infantry Regiment |

American Artillery firing on Sitio Suyac from Maasin

|

Rev. Zacarias Dayot, a Filipino Baptist minister, reported the American artillery killed twenty six Japanese soldiers and one carabao, but no civilians.

- 160th Infantry Regiment

Lieut. Sadayoshi Ishikawa narrates the movement of the Saito forces. While he doesn't mention the Japanese civilian suicide, he does mention that exhausted civilians were hampering the movement, their arrival at Sitio Suyac, and the American artillery bombardment of that place:

ACTION AND MOVEMENTS OF THE TORAO SAITO ADVANCE GUARD

When the advance guard had become separated from the main body, following the penetration of the guerrilla positions near Jaro on March 20, the advance guard proceeded to Pavia. Here the unit reorganized and then continued the march, accompanied by Japanese civilians and hospital personnel, to some cocoanut groves north of Pavia. Hearing of the approach of American tanks and of combat units from around Santa Barbara, 1st Lieutenant Kunio Yamamoto, who was in command, ordered preparations for the pending encounter; civilians and hospital personnel, meanwhile, withdrew to the banks of the Jaro River. At 0900 on the 20th, after briefing the commanders, the guard proceeded northward for approximately two kilometers and took cover in a bamboo thicket.

Concurrently, efforts were made to communicate with battalion headquarters but the American tank action, and artillery bombardment of the Pavia area during the day, prevented the communications section from making contact with the battalion. Convinced that the advance guard would be unable to rejoin the battalion, Lieutenant Yamamoto ordered it to begin the withdrawal into the hills.

On the 21st, the civilians were rounded up and escorted to the railway line running about five kilometers northeast of Santa Barbara where they concealed themselves in a bamboo thicket adjoining the tracks and waited nightfall. After dark the withdrawal nortward was continued but the march was hampered so much by exhausted civilians that Buyo, four kilometers northeast of Cabatuan, was not reached until daybreak. Here, once again, the advance guard resorted to the cover of cocoanut groves and bamboo thickets to escape air observation.

In the early morning of the 23rd, the guard and civilians crossed over from the Cabatuan to the Janiuay Road and arrived north of Tigbauan at 0800. Here they were subjected to a howitzer concentration, delivered from the direction of Maasin. Approximately ten were killed in this bombardment; finally, continuation of the move toward the hills near Bongbong took the unit out of the area under fire.

The Bongbong hills proper were gained the next night.

- Lieut. Sadayoshi Ishikawa