|

by Col. Hiram W. Tarkington

Commanding Officer of the 61st Field Artillery Regiment (Philippine Army)

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: The 61st Field Artillery Regiment had maintained its headquarters at Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines, for some time before the start of WWII in Panay Island. That is mentioned here, in this memoir of Col. Hiram W. Tarkington, the commander of the 61st Field Artillery Regiment. The 61st Field Artillery Regiment transferred to Cabatuan, Iloilo about December 8, 1941. They left the town on January 1, 1942 when they relocated to Mindanao. |

Note from John B. Lewis:

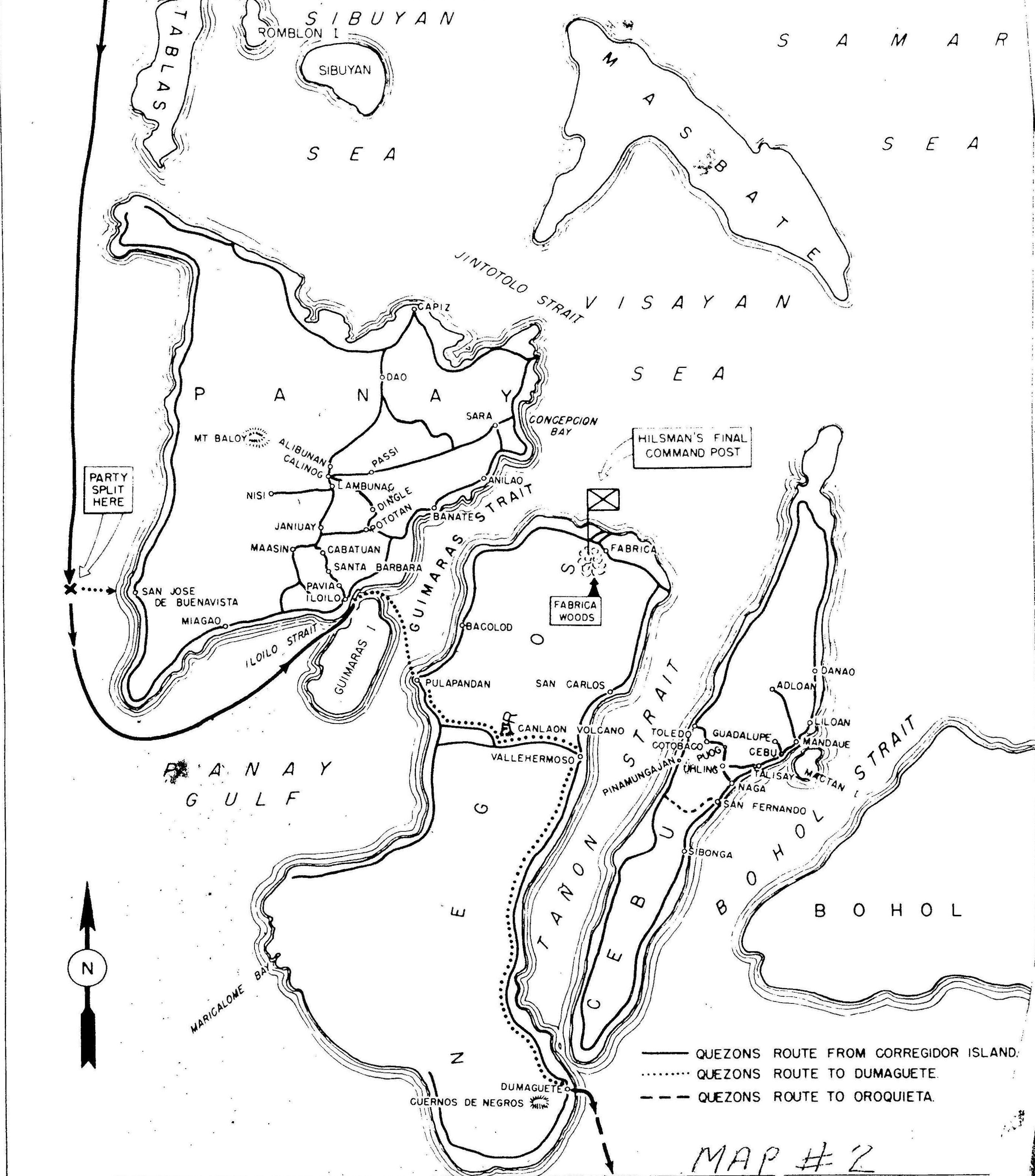

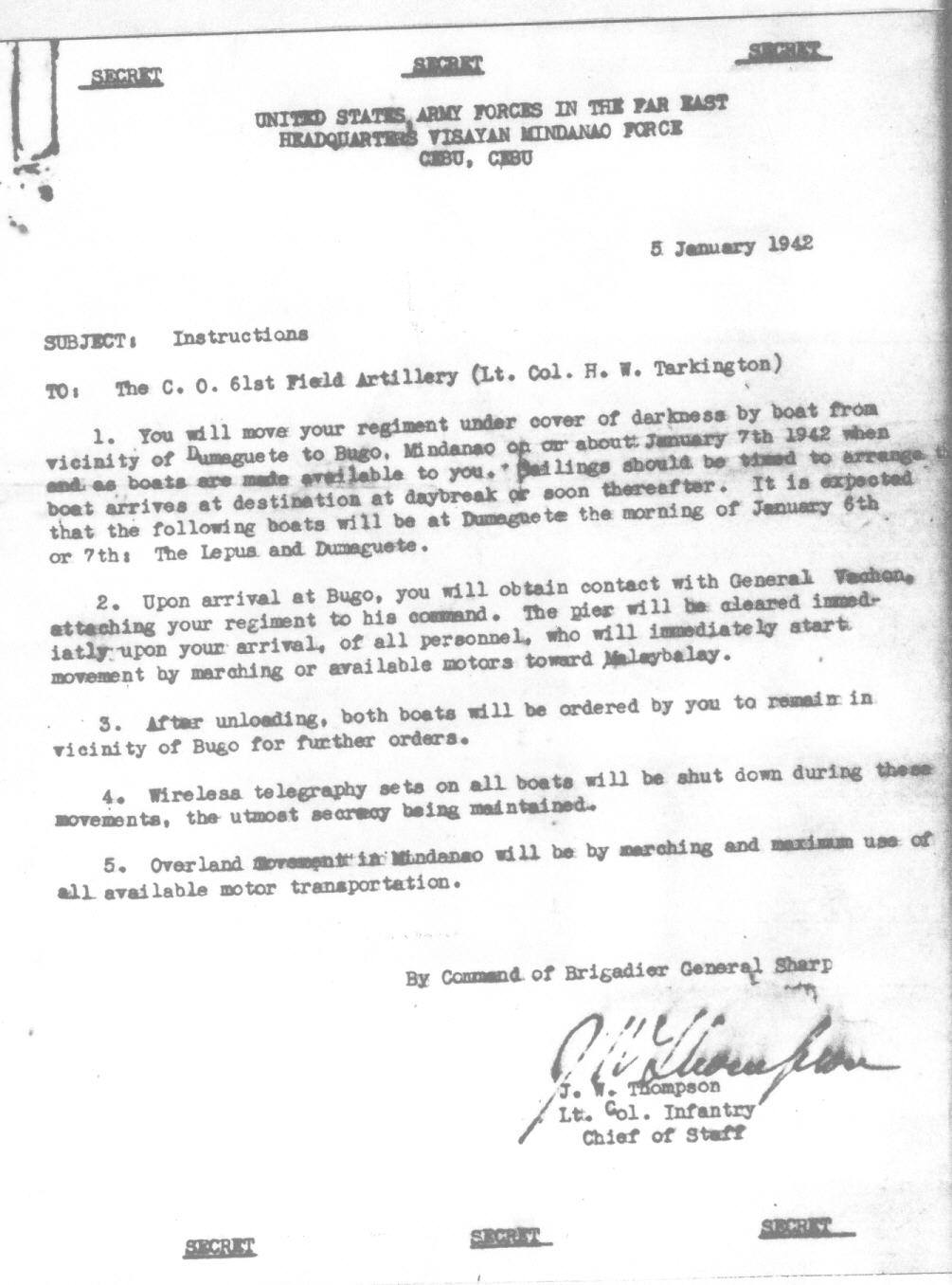

This is a manuscript that, unfortunately, was not published. The maps cited in the manuscript were not available when I found the manuscript in the Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA in 2005. Recently (April 2011) I gained contact with a grandson of Col. Tarkington and he was able to provide copies of the maps and several related documents. Now I am making this "treasure chest" of information (in my opinion) available to persons wanting information about the defense of the Visayas and Mindanao during December 1941 through May 1942.

- John B. Lewis

Headquarters of 61st Field Artillery transfer to Cabatuan, Iloilo

HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales sinking

Japanese Occupation of Guam

S.S. Corregidor sinking

Japanese bomb Iloilo City

MacArthur says no to Martial Law

Intelligence Gathering

Crew of crashed B-17 bomber, attach to 61st Field Artillery, arrives in regimental headquarters Cabatuan Iloilo

Col. Tarkington, 61st Field Artillery, brings Corporal Wollman to his headquarters in Cabatuan, Iloilo

S.S. Panay sinking

Baus Au

Lieut. Col. John L. Lewis at Cabatuan to keep up impetus of regular training activities

Series of Innoculations initiated at Cabatuan, Iloilo

61st Field Artillery leaves Cabatuan, Iloilo for Mindanao

CHAPTER I - TOWER OF BABEL

DECEMBER 7, 1941

The sleek little interisland steamer Mayon rolling gently up Iloilo Strait had never been as beautiful as she appeared tonight to the little group of weary Americans waiting on Guimaras Pier.

MAJ. GEN. WILLIAM F. SHARP AND HIS STAFF, 1942. Back row, standing left to right: Maj. Paul D. Phillips (ADC) and Capt. W. F. O'Brien (ADC). Front row, sitting left to right: Lt. Col. W. S. Robinson (G-3), Lt. Col. Robert D. Johnston (G-4), Col. John W. Thompson ( C of S ) , General Sharp (CG), Col. Archibald M. Mixson ( D C o f S ) , Lt. Col. Howard R. Perry, Jr. (G-1), Lt. Col. Charles I. Humber (G-2), and Maj. Max Weil (Hq Comdt and PM). Photo from https://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/5-2/5-2_28.htm |

As we drove through the warm, quiet Sunday dusk toward headquarters and mess the little city of llo seemed so peaceful we could close our eyes and believe, for a moment, that we were home, in Charleston. Or Long Beach -- or Jacksonville. But only for a moment, until our still-Occidental nostrils, again assailed by that exotic redolence blended of frangipani, decaying fish, ginger flowers, dirty streets and horse manure, jolted us back again into Oriental reality.

For this was the Philippines, on December Seventh, 1941, and we knew that the cat was about to jump.

We had been expecting it for weeks, hoping against hope to have a little more time to make soldiers out of our barefooted taos. Time! Time to teach our willing but raw recruits which end of a gun shot (with twenty-year-old infields bigger than they were.) Time! Time to train leaders. Time to accumulate supplies of food, rifles, artillery pieces, ammunition, shoes -- all the sinews of war -- from Manila or from the states. Time to implement our deficiencies with local resources. TIME!!

But it was no particular surprise when Captain Gavino, my senior Filipino officer, came to my quarters at Dingle the next morning as I was dressing, his usual cheerful manner grave, his message grim.

"Pearl Harbor has been attacked, Ser! The report was just received from Iloilo radio station."

Pearl Harbor! And we had thought the first strike would be made at the almost defenseless Philippines!

To news of such import from unconfirmed, unofficial sources, the first reaction was sharp disbelief. Especially since the report had been received through a local radio station, somewhat garbled, and no doubt exaggerated, by native hysteria. Was this rumor perhaps a Japanese device to create confusion among the Filipinos?

The Islands were permeated with a substantial percentage of Japanese nationals as well as a considerable number of native fifth-columnists, from whom the fomentation of disorders could be expected. Kurusu was still in Washington, and even though an Associated Press dispatch from Manila had quoted him on his stop there on 8 November as having "not much hope" for the success of his "peace mission", it was incredible that Japan would actually disregard international amenities to this extent!

Anyway, the Division Commander's conference, scheduled for this morning in Iloilo had not been cancelled. I was due there at nine o'clock and had barely time to make it now. If the raid on Hawaii were a fact Colonel Chynoweth would know. Meanwhile, rumor would wait on fact and no conjectures would alter the training program. But security measures would be observed with even more than the usual vigilance, just in case.

Upon arrival at Division Headquarters, it was immediately apparent that the fat was in the fire. During the conference, official verification arrived from USAFFE in Manila, and shortly thereafter, the tragic report of the bombing of Baguio, lovely summer capitol of the Islands, where all of us had spent many happy days.

In the light of the changed international situation, plans for a tighter defense of the Islands were discussed and decisions made as to the transfer of troops from training areas to tactical positions. We said goodbye to Mitchell, who left immediately for Negros to assume command of his regiment, the 61st Infantry. Colonel Christie was given command of the 63rd Infantry, on Panay. These officers had come out to Manila from the States with Colonel Chynoweth on the Army Transport Coolidge in November but a snarl of the usual red tape prevented them from reaching their assignments as rapidly as Colonel Chynoweth. As a result, they were thrown into the picture cold, with no chance to orient themselves or to acquaint themselves with the capabilities and limitations of their officers and men before war broke.

The conference ended with a keener realization on all our parts of the gravity of the situation, and a deeper appreciation of the responsibilities of command, as we returned to our various stations to carry out the new dispositions.

Shortly after my return to Dingle, news of the raids on Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg, on Luzon, which we had so recently left, came in. Remembering the concentrations of planes in their neat, peacetime rows; the dummy planes spotted within fragment range of quarters; the Sawali barracks of woven palm fibre nudging the edges of the field; we marveled -- not for the first time -- at the lack of vision thus exhibited.

It had been felt that war was imminent for approximately a year. The last of the wives and children had been returned to the United States by decision of the State Department in May of '41. In spite of the keen anxiety which pervaded the scene it was not until 15 November that fighter aircraft were placed on twenty-four-hour alert, fully gassed and armed. Not until 29 November was the Army placed on alert with all leaves cancelled. Not until 6 December did Major General Brereton place all air units on alert with combat crews and maintenance crews constantly ready for duty.

Although the first measure passed by the Philippine National Assembly, after the inauguration of the Philippine Commonwealth in November 1935, had been for the establisheent of a Philippine Army, it was not until January, 1937, that the first class of trainees, 20,000 strong, were assembled for a full five-and-one-half months period of instruction. Even then training facilities were so handicapped by lack of funds and shortages of equipment that no unit training was attempted, and very little in the use of weapons.

since early Spring, 1941, General George Grunert, Commander of the Philippine Department, had been attempting by every means available to him to obtain through Washington desperately needed supplies and equipment, but with little tangible result.

JULY 25, 1941

On 25 July 1941, retired General Douglas MacArthur was Field Marshal of the Philippine Army. On 26 July, President Roosevelt authorized the organization of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) and appointed MacArthur commander. Now -- it was hoped! -- some of that vast stream of planes, arms, military supplies of all kinds being poured so freely into Europe and Africa would be diverted to the Islands, and that there might then still be hope of fashioning some sort of effective military organization in time to stop the Japanese juggernaut, which was even then rolling on into Indo-China.

The formation of USAFFE, however, superimposed a higher headquarters over existing Headquarters Philippine Departnent, and since, at that time the only American forces in the Far East were those of the Philippine Department, there existed from the origin of USAFFE a confusion as to the prerogatives of these higher headquarters. After the mobilization and induction of the Philippine Army, a third higher headquarters -- "Headquarters Philippine Army" -- entered into the command picture adding further complications. In operation there existed from the beginning a duplication of effort which resulted in conflict of orders and denials of responsibility.

AUGUST 15, 1941

On 15 August, General Grunert held an orientation conference in Manila, during which he stated that he had been given the mission of mobilizing and training the Philippine Army; that the first increments would be inducted into the Service of the United States on 1 September 1941, and that the training of these inductees would be such as to have them ready to "defend the beaches" by 15 October 1941.

At this conference, Colonel William F. Sharp was assigned to command the Visayan-Mindanao Force, which included all the southern islands of the Philippine Archipelago. District commanders (or instructors, as they were then called) for the individual islands were also designated, more or less arbitrarily, at this meeting, as were the members of General Sharp's own staff; and all were unknown to him prior to this time. (See appendix 1). Headquarters, Visayan-Mindanao Force, was to be established at Fort San Pedro, Cebu City, Cebu.

The mission assigned to the Visayan-Mindanao Force, in brief, wns to defend the islands of Panay, Negros, Cebu, Bohol, Samar, Leyte and Mindanao from invasion by the Japanese; to build, develop and expand airfields throughout these Islands; and to prevent supplies and materials from falling into enemy hands.

Just prior to war, commanders for the divisions were assigned to and joined the Force: Colonel Bradford G. Chynoweth to the 61st Division on Panay and Negros; Colonel Guy O. Fort the 81st Division, organizing on Cebu and Bohol; and Colonel Joseph P. Vachon the 101st, assigned to the Cotabato-Davao area of Mindanao.

Colonel Fort had a background of many years in the Philippines in command of various Philippine Constabulary units. Colonel Chynoweth had spent his boyhood in Zamboanga during his father's tour of duty there under General Arthur MacArthur, father of Douglas MacArthur. Chynoweth and Vachon, both officers of many years' experience and service, had come out to the Islards together on the Coolidge arriving on 20 November 1941, the last transport to reach Manila.

A favorite topic for discussion aboard the transport had been how best to solve the desperate problem of Philippine defense. The pros and cons of Douglas MacArthur's statement on this question, made in June of 1939, were recalled. He had asserted at that time that, in his opinion, the cost of an invasion of the Philippines would be prohibitive in both lives and dollars. Also, that he believed not only that Japan would be strategically weakened by the possession of these islands, but that the generally accepted promise that Japan coveted the islands was erroneous.

Perhaps, in the intervening years, he had revised his opinions. In any event, it was generally conceded aboard the Coolidge, despite the respect accorded MacArthur's vision and sagacity, that if the Philippines were not coveted and marked for attempted acquisition by the Japanese, that their foreign policy had been skillfully and systematically misleading. It was felt that the Japanese must eventually attack or be compelled to accept loss of face by abrogating their entire concept of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".

It was generally doubted if the Japs could be prevented from making landings. But it was agreed that the Filipino troops could be trained up to such a degree of mobility that we could lead the Japs on and then fall on their flanks and destroy them. Word had gotten around that MacArthur had trained an army of half-a-million men, and that it remained only for the finishing touches to be put on their training. "The valor of ignorance!" The Philippine Army was an army in name only. It didn't even have basic combat training. And even had the training been completed the equipment for any sort of intensive action was totally lacking.

Bradford G. Chynoweth |

By the time Colonel Chynoweth arrived in Iloilo on 24 November, he had already been disillusioned to some extent about the efficacy of his new command. During the period of impotent inertia in Manila, anxiously awaiting orders, he had dropped in at the Army and Navy Club one night and encountered an old friend, Colonel C. P. Stivers, now personnel officer of USAFFE. This was the man! Immediately he besought Stivers for information concerning his assignment, and the news he received was a body blow. He was for the 61st Division of the Philippine Army, in Iloilo, and Pete Vachon was to have the 101st, in Mindanao. The very two assignments they had joked about on the ship as being backwaters and jumping-off places, too far from the main show on Luzon ever to see any action. And now, like Job, the very things they had dreaded had come upon them!

Concerned, Chynoweth set about prying all available information out of Stivers relating to the new command. "Do my troops have the new M-1 rifle?" he asked.

Stivers threw back his head and roared with laughter. "No", he replied, when he could speak again, "and it's easy to see from that question that you haven't been in the Islands long this time. These troops don't even have Springfields!"

Well, for God's sake, what do they have?" Chynoweth implored.

And then Stivers gave him the works. Such of the troops as had guns at all had enfields -- long, old, 1917 Enfields for these tiny Filipinos. And there weren't even going to be enough of those to go around by the time mobilization was completed. The division artillery was to have only old rountain guns, on little wooden wheels, obsolete a quarter-century ago, but all that was available. No new motors, no trucks, no jeeps, few American officers, few trained officers of any sort. That was the deal. And there wouldn't be any aces in the hole either, barring miracles.

The next day, from MacArthur himself, came the warning that Chynoweth would find little in the way of equipment in his division, and that there was no hope of obtaining more. But the General did offer the cheering (although misleading) information that the troops would have one great advantage in that they would be fighting on the very beaches and terrain over which they had trained.

Some glimmer of optimism still persisted, then, until over the luncheon table in Fort San Pedro that first day in Iloilo, Colonel Chynoweth began, with enthusiasm, to tell his staff of his plans for training the 61st Division. Of the unbelievable mobility they would achieve, and the decentralized, all-out instruction which would fit them for blitzkrieg, in spite of the handicaps of equipment shortages.

The polite skepticism with which his remarks were received annoyed him, and he let it be known, unmistakably. It was Allen Thayer, the fine, young lieutenant colonel of the 62nd Infantry, who finally braved the storm.

"Sir, I am afraid you have been misinformed as to your division's potential. Certainly as to its abilities". Courteously, but positively, positively, Thayer went on. "The troops have no basic training upon which to build -- the regiments, at this point, are little more than mobs! Furthermore, the few Filipino officers and non-commissioned officers (except for the half-dozen regulars from the Philippine Scouts) have had so little training themselves that they are useless as instructors."

The Division Commander was appalled, but Thayer wasn't through with the bad news yet.

"We have about a dozen American Reserve Officers in the entire Division, who are fairly well trained but without combat experience. They speak only English. The Filipino officers speak mostly Tagalog, and many do not understand English too readily. The men speak a variety of dialects, understand English little or none and Tagalog only slightly better!"

What a Tower of Babel this outfit was going to be! The resulting confusion in orders was enough to drive a saint mad -- and if there were any saints in the Sixty-First, their presence had not been felt.

The language problem continued to be a most baffling one throughout the campaign. At one time, in the 61st Field Artillery Regiment, in addition to English, Tagalog and Visayan, there were fourteen native dialects represented, none of them mutually understood. When one considers that there are eight languages and eighty-seven dialects spoken in the Philippines, and that less than one out of four inhabitants at that time spoke or understood English, the lack of coordination in our troops is not difficult to comprehend. No organization can function very brilliantly when it has to talk to itself in sign language!

Colonel Chynoweth was to recall many times, and with amazement, General MacArthur's statement to him in Manila -- that these troops would be fighting over the very terrain on which they had trained -- and wonder if the General had been merely trying to be encouraging, or if he had been misled or misinformed by his own staff, for none of these men had had any combat training on any beaches or terrain.

Presumably some of the reservists had been given five months' training, of sorts. Their progress was about what one would normally expect of American recruits in three weeks. Some of the men were armed with the Enfields which had caused Stivers so much ironic amusement, but the number of rifles available was wholly inadequate, and fifteen percent of those had broken extractors, for which there were no replacements. Furthermore, the men didn't know how to shoot. Even the few reservists had had only five rounds, in training -- just enough to teach them how to load and squeeze the trigger. And we couldn't train them now because we had no ammunition to spare. It must be saved for grimmer business. Most of the men, plucked bodily from their peaceful rice paddies a few short weeks before, had never even held a gun in their hands. Nor was this the half of it!

And this, then, was the instrument with which we were to repel a thoroughly-trained enemy, excellently equipped and seasoned by years of conquest!

But by this time there had been so many unpleasant surprises and disappointments that the very hopelessness of the situation became a challenge. 'We'd find a way to beat the game yet!

The 61st Division was to consist of the 61st, 62nd, and 63rd Infantry Regiments, the 61st Field Artillery, the 61st Engineer Battalion, and the 61st Medical Battalion, with Headquarters at Iloilo. Of these, the 61st Medical Battalion was mobilizing and the 63rd Infantry about to begin mobilizing. The other elements had just completed or were nearing the completion of their mobilization.

The guns for the artillery were not on the Island. Headquarters in Manila, adhering strictly to peacetime routine, refused to ship them until the necessary magazines and warehouses had been constructed. These had not even been begun. There was, however, one bright spot in the all-pervading gloom when about 30 November we received a small shipment of ammunition, including sufficient rifle ammunition to bring our supply up to about 60 rounds per rifle, and a limited amount of artillery ammunition. These supplies were under the oontrol of two American Ordnance non-coms, who were considerably perturbed over the lack of proper facilities for storing this materiel. We were, however, too cheered and encouraged by the arrival of these necessities to be disturbed by the mere lack of warehouses. Now, if Manila would just send our artillery pieces -- !!!

The three training camps, at Anilao, Dingle Barracks, and Pototan, were just being built. And it appeared that here, as at home, political considerations outweighed military requirements in the selection of camp-sites. The training areas were too small, the roadbeds were poor. the water supply so inadequate that it was difficult to obtain even enough for the kitchens, for cooking and drinking. There was not even a probability of procuring a sufficient supply for the showers.

Recommendations were immediately made to USAFFE that urgent steps be taken to rectify these situations. But before any action could be taken, Pearl Harbor, and Brereton's "Little Pearl Harbor" at Clark Field, flashed across the screen, and permanent campsites ceased to be important.

CHAPTER II - THE WEST BANK OF THE POTOMAC

Headquarters of 61st Field Artillery transfer to Cabatuan, Iloilo

Since the outbreak of hostilities had caught us with a division just mobilising and untrained, we had, obviously, to revise our original plan of action. We were assigned to protect two islands comprising approximately 10,000 square miles or slightly larger than the State of New Hampshire and with many hundreds of miles of vulnerable coastline. We had insufficient arms, no artillery, and only 60 rounds of ammunition per rifle. Colonel Chynoweth, therefore, modified the plan on his own initiative, to provide for a deep delaying action culminating in a final, mobile defense in the mountain masses.

In order to have freedom of action to cope with a situation developing on any front, the Division command post at this tine was moved inland from Iloilo to Santa Barbara, a barrio about ten miles north of Iloilo on a good roadnet leading to all parts of the Iloilo front and on the principal highway leading to Capiz, the second important town of Panay, on the north coast. Troops were disposed into tactical positions with outposts covering the important localities on the beaches and reserves well back.

The 61st Field Artillery (Without artillery pieces) which had been training at Dingle, a small barrio about 26 kilometers northeast of Santa Barbara, was moved in accordance with new troop dispositions into Division reserve, with headquarters at Cabatuan. One battalion under Lt. Murphy was initially stationed at Janiuay, and a detachment under Lt. Yield provided security for the Santa Barbara reservoir.

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir:

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir:I was in contact by email with John B. Lewis, son of Lieut. Col. John L. Lewis of the 61st Field Artillery, before John B. passed away, and I pointed out to John B. that it was mentioned in "There Were Others" that the 61st Field Artillery was headquartered in Cabatuan, Iloilo, Philippines, and he revised on July 1, 2012, the profile of his father that he posted online to reflect this, even highlighting his changes in blue. See In Memory of Lieut. Col. John L. Lewis. |

The newly-mobilized 62nd Infantry, under command of Lt. Col. Allen Thayer, which had been covering the southeastern coast in the Miagao-Banate area, was pulled out and sent north to guard the Capiz front; being relieved in the Iloilo sector by the embryo 63rd Infantry under Lt. Col. Carter McLennan, and with a platoon of the 61st Field Artillery at Sara as an intelligence link covering the important road Junction in the vicinity and possible landing spots on the coast of Concepcion Bay.

Meanwhile, on the other islands of the Visayan-Mindanao group, the island commanders were experiencing the same kind of headaches we were having. Colonel Mitchell, on Negros, had discovered that although his regiment, the 61st Infantry, had been mobilized for some time, training was still in the most rudimentary stages. Captain Floyd Forte, the former regimental commander, and Captain Van Nostrand, his executive, both fine officers, had done their best, but again the troops simply had no foundation upon which to build.

Colonel Cornell, on Leyte, was handicapped by the same chaotic conditions, as were Colonel Vachon in Mindanao and Colonel Fort in Cebu.

At this time Radio Manila (KZRM) was broadcasting the progress of the invasion on Luzon. Tempered with optimism and paying tribute to the staunchness of the defenders, these broadcasts went far toward allaying fear and preventing hysteria among the populace.

It was, however, apparent to the objective military mind that in spite of stubborn resistance, the defending forces were withdrawing; according to plan, into the Bataan peninsula to make their final stand.

This fight for Bataan, in the face of staggering odds in equipment and the other combat necessities, by the starved "Bastards of Bataan" is epic. There never was a finer fight or so tragic a conclusion. Frank Hewlett's little verse which so aptly expressed the lament of the survivors of this trial by fire, has always struck a deep inner chord and pointed the accusing finger where it properly belonged:

"We're the battling bastards of Bataan,

No momma, no poppa, no Uncle Sam,

No aunts, no uncles, no nephews, no nieces,

No rifles, no guns or artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn."

HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales sinking

DECEMBER 10, 1941

Captain Price, one of the battalion commanders of the 61st Field Artillery Regiment, had brought with him from the States a Hallicrafter receiver and with this we listened to the reports of disaster as they continued to flash across the world -- from KZRM in Manila, from KGEI in San Francisco, from Radio Tokyo. These reports were not always in agreement with our military intelligence, but were useful in following the general trend of events. Thus were we apprised of the progress of the seige of Wake, whose baptism of fire followed so closely that of Pearl Harbor, that same fateful day. Of the amputation, by Japanese torpedo-bombers off the coast of Malaya, of those modern fingers of the British fleet, the "Repluse" and the "Prince of Wales" on 10 December. And on the same day, the leisurely, precise and absolute destruction of the Cavite naval Base on Manila Bay, by more bombers.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: Repluse here is Repulse. The British warships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales did go down on December 10, 1941 off the coast of Malaysia |

Japanese Occupation of Guam

DECEMBER 11, 1941

On the eleventh, Tokyo gleefully announced the occupation of Guam after one day of fighting, and the capture of its Governor, Captain George Johnson McMillin, USN (he whom the Chamorros, in respectful admiration, had dubbed "King of Guam"). This tiny atoll, boasting only a token force of Navy and Marine personnel, lying close to the great Japanese arsenal of Rota, which on clear days was plainly visible from the Governor's verandah, was completely unfortified. This, according to one version, "because Congress could see no farther than the west bank of the Potomac!"

Hong Kong, battling for existence; Malaya with its "impregnable" Singapore bastion, reeling under the blows of the little yellow man, its guns pointing endlessly and futilely seaward. Cunningham, Devereaux and Wilson with their little bands of stalwarts, trading punches with the Japs at Wake.

How far could Tokyo spread and conquer? How bolster vanishing morale? How soon would the blow fall on us?

Questions offset by feverish activity. No time to think of consequences. No time even to whip our forces into a semblance of an efficient, reliable tool of war.

S.S. Corregidor sinking

DECEMBER 16-17, 1941

We were still without even the barest necessities in the way of equipment. Manila had been promising to ship us our artillery by the "first available transportation", but aggravating delays proved the rule rather than the exception, and it was not until 13 December that USAFFE advised that the 2.95 mountain guns and ammunition, as well as other vitally needed equipment, were leaving on the interisland steamer Corregidor. We were elated! Now, maybe, we'd have something to work with. Even if the runs were old-fashioned, and cumbersome with their little wooden wheels, they would help materially. And what a morale boost they would be!

But our joy was short-lived. Next morning Colonel Chynoweth arrived at his headquarters weary after a steamingly hot night in the little nipa but which then constituted his quarters; eaten alive by mosquitoes and kept sleepless by the continual yapping of the Filipino dogs with which every barrio swarms; buoyed up alone by the thought of the imminent arrival of the Corregidor; to find Colonel Quial waiting with the worst piece of news yet.

The Corregidor had been sunk!

Steaming, blacked out, through the murky gloom of the tropic night, she had somehow run past the Navy launch which wee to guide her through the minefield guarding the mouth of Manila Bay. In a matter of moments a sheet of flame wrote a tragic epitaph for more than 500 of the 800-odd refugees aboard the little ship.

The extent of this catastrophe numbed for the moment the realization of our own disaster in the loss of the Corregidor's cargo. Even though the guns were antiquated and unwieldy they would have provided some small measure of support for the infantry.

Now it appeared that we were to be reduced to fighting a war without guns. And it came to just that in certain instances later on.

Japanese Bomb Iloilo City

DECEMBER 18, 1941

The Japs didn't give us much leisure to worry over spilt milk in the loss of our supplies. Four days later, just at lunch time, someone called out that there was a big formation of planes overhead. Everyone rushed out, hopefully, craning their necks, and counted 18 planes, very high up and in perfect formation, going north. They appeared to be silvery-green in color and no markings could be distinguished. The first reaction was one of great relief. This must be the first of the long-promised "Help" for Luzon!

But the planes slowly circled heading southward again, just as a second formation of 17 bombers appeared from another direction. It was obvious now that they were enemy planes.

Colonel Chynoweth hurried back to his command post at once, observing on his way huge plumes of smoke billowing over Iloilo. As he arrived at his command post a Filipino officer ran up with word that the airfield at Iloilo had been severely bombed, with some bombs also falling in the town and doing extensive damage. The officer reported many casualties, and added that the troops were demoralized and an enemy landing about to take place!

Colonel Chynoweth drove immediately to the airfield, and found a scene of utter confusion. Shortly before noon, a battalion of the 63rd Infantry which had just been mobilized on Romblon Island, had landed at the dock, with orders to move inland immediately. Instead of proceeding, as ordered, they had stopped at the airfield to have lunch and were caught like sitting ducks as the Japs swept over.

The Combat Company, Headquarters Battalion, 62nd Infantry, which was still stationed at the field, promptly mounted its .50 caliber machine guns and went into action. The excitement of their first engagement with the enemy, under heavy aerial bombing, plus their total lack of experience in firing at speed targets, enabled the enemy bombers to escape without casualty.

Colonel Carter R. McLennan, the 63rd's regimental commander, arrived at the field while the bombing was in progress, and at great personal risk succeeded in getting some of the men into foxholes, and restoring a degree of order. Had it not been for his gallant conduct in risking his own life the catastrophe would have been worse. Even so, nearly two hundred were killed or wounded, including some civilians. Colonel McLennan was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his action on this occasion.

Several bombs had dropped in the city, one making a direct hit on a girl's convent and others wrecking homes in the residential section. A large number of the oil tanks in Iloilo had been set afire by tracer bullets and the towering flames and thick, black smoke from these fires added a Dantesque touch to the scene. Two sugar warehouses were burning; and all but one of our patched-up but precious "aircrates" had been destroyed.

Major Deter, Division Surgeon, had instituted prompt evacuation of the wounded, but the work was greatly handicapped by lack of sufficient medical supplies, especially anesthetics and morphine, to care for such a heavy load. Chynoweth said later that this was the first time he really knew what a strong right arm he had in Deter.

"The Major had come to me", he remarked, "with the reputation of being hard to handle. He was, too -- just like a race horse. You held him back and he went crazy. You gave him a job to do and all hell couldn't stop him. On this occasion he was phenomenal! He scoured Panay for every conceivable source of medicine. There wasn't enough. So he hopped into a speed boat with old Pop Heise and they went clear over to Cebu. Before the Cebuanas knew what had happened he had corralled a large part of the available supply of morphine on Cebu and was on his way back! Just north of Negros a Jap patrol plane spotted his tiny craft and harrassed him by repeated attention and machine-gun attacks most of the way back to Iloilo. Finally dodging his persecutor, in a few minutes more Deter was back at the field, working over the wounded as calmly as if he'd just been down to the corner drugstore for some aspirin!"

As the Division Commander had neared the airfield, during the bombing, he was surprised to find the troops along Fort San Pedro falling back to the rear. They stated that a Japanese cruiser was just entering the channel outside Guimaras. The commander inquired if all the men had ammunition and discovered that the troop commander had forgotten to issue any! The matter was of small consequence, actually, since the few boxes of ammunition available would have made very little impression on the enemy, but it is a classic example of the rawness and complete lack of training of the Filipino officers and non-coms at that time.

Chynoweth then hastened out to the point to investigate the reported Japanese cruiser, which, on closer investigation, proved to be one small interisland tug coming home. this reprieve drew a heartfelt sigh of relief from Chynoweth. Things were bad enough as they were, but an enemy landing under the chaotic conditions of the moment could have been very, very bad.

Aside from the actual loss of life and destruction of property, however, the disastrous effects of this initial bombing of Iloilo were much more far-reaching. The Governor* of the Province, never a strong character, left to completely demoralised, as did the Mayor, and all governmental functions simply ceased. The populace, already unnerved by the bombing, and anything but comforted by these events, also left town in large numbers, and business was rapidly going to hell.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: * The Governor of Iloilo being referred here is Oscar Ledesma who preceded Governor Tomas Confesor in 1941-1942. That's why later in 1942 when President Manuel L. Quezon heard that Confesor had returned to Iloilo after the Japanese invasion of Luzon, Quezon immediately looked for Confesor and promptly appointed Confesor as Governor of Iloilo replacing Ledesma. |

MacArthur says no to Martial Law

Don Carlos Lopez and Thomas N. Powell, Sr., two influential citizens of Iloilo, implored Colonel Chynoweth to establish martial law and take over the government of the island. They claimed that if the situation continued as it was headed -- which it would unless drastic action were taken -- that even the harvesting of crops would cease and the island soon fall into anarchy.

General MacArthur had been most definite in his instructions that Civil government should not be interfered with, and Colonel Chynoweth was reluctant to declare martial law except as a last resort. He would first confer with the fugitive governor* and try to buck him up sufficiently to keep the wheels turning.

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: * The Governor of Iloilo being referred here is Oscar Ledesma who preceded Governor Tomas Confesor in 1941-1942. That's why later in 1942 when President Manuel L. Quezon heard that Confesor had returned to Iloilo after the Japanese invasion of Luzon, Quezon immediately looked for Confesor and promptly appointed Confesor as Governor of Iloilo replacing Ledesma. |

Before such a conference could be arranged, however, a courier, Lt. Col. Braddock, arrived from Force Headquarters in Cebu, bringing instructions from the Force Commander directing the setting up of military governments in all the Southern Islands. Braddock forthwith arranged a meeting with some of the local residents, including Tom Powell, Sr., at which time he made public the Force Commander's instructions, and proclaimed Colonel Chynoweth military governor of Panay.

One of the citizens spoke up and said, "What about Manila? What are they going to think about all this?"

Braddock replied: "Manila has forgotten all about us. We are going ahead on our own!"

Following the instructions which Braddock had brought, Chynoweth appointed the necessary officials to conduct the affairs of the government, designating Tom Powell, Sr., as Civil Administrator -- a post requiring sound Judgement, integrity, and vision -- all of which Powell possessed in abundance, and Colonel McLennan was detailed to act as immediate liaison officer and assistant to Powell.

Many of the agencies of the government which had been evacuated after the bombing now began to dribble back slowly. Storekeepers and other workers who had fled to the mountains began to return, and before long business was functioning with relative smoothness.

MacArthur eventually heard of General Sharp's action in setting up military law and ordered it revoked, but by that time Powell had the situation so well organized that it made little difference.

Intelligence Gathering

Along with everything else, the first few weeks of war had provided us with an interesting demonstration in mass psychology. There being virtually no Army signal equipment available, we were forced to rely on the commercial telephone lines which were poor, at best, being ground return. An island intelligence net had been built up, composed mainly of postmasters and school teachers throughout the island, who had telephones. The reports which poured into headquarters over this network were so amazing at first as to seem that the population was composed entirely of Munchausens. We soon discovered, however, that it was not lies, but imagination. Every sugar barge became a battleship; every seagull flashing in the sunlight an enemy parachute! Fortunately, the enemy did not attempt landings at once and the populace steadied within a month or two.

Then there was espionage. We had a large corps of self-appointed agents who turned up spies on every corner. Trust nobody! Your neighbor is signalling to the Japs! Investigating, you find him peacefully reading a book while the bamboo fronds waving in the breeze in front of his window convert his steady reading lamp into a dot-and-dash affair. Spies! It all sounds very amusing now, but then the hot-heads wanted blood. They literally wanted the Army to put these suspects up against a wall and shoot them. One prominent American civilian would scarcely speak to the Division Commander because, during all those feverish months, he did not order a single suspect shot:

About 20 December reports were received from some of our self-appointed but well-meaning "espionage agents" that Lake Baloy was being used by the enemy as a seaplane base. This was, of course, possible, but seemed scarcely within the bounds of probability. Nevertheless, like all the other cries of "Wolf!" it had to be investigated.

Lake Baloy is a good-sized crater-lake at an altitude of about 5600 feet on Mount Baloy, accessible only by plane or by exceedingly steep and hazardous mountain trails. Third Lieutenant Filemon. Lacsi, regimental adjutant, 61st Field Artillery, with a detail of one Constabulary officer and four enlisted men, was ordered to Lake Baloy to investigate this reported enemy activity. After an arduous eight-day trip he reported that a thorough search of the lake and surrounding country failed to reveal any indications of enemy activity, past or present. It was just another case of over-developed imagination on someone's part.

This strenuous expedition was not wholly wasted effort, however, for Lacsi's report of this terrain was largely responsible for this area being utilized by General Christie as his headquarters after the Japanese invasion of Panay on 16 April.

Probably the worst headache during those first weeks was property. The troops had virtually no equipment. The old comparison of Washington's Continental Army continually arose in one's mind. Like them, our men were barefooted, though they waded in swamps instead of snow. Like teem, they had little food, less clothing, no blankets -- and the tropics can be cold at night, and damp. So requisitioning, was instituted -- of everything that could be converted to Army use. Shoes, blankets, flashlights, mess equipment, and countless other items, including motor vehicles. At the outbreak of war we had just one truck and one autumobile under our control!

Our naive troops got the idea, then, that if the Army could requisition for them, they could do a little confiscating on their own hook, and it wasn't long before they were walking into stores and walking out with anything they wanted. Or (and this applied particularly to some of the Filipino officers) stopping fine automobiles on the street and taking them over in the name of the Army. This led, very naturally, to displeasure on the part of many civilians, but because we had so few responsible native officers and non-coms and because our organization was still not complete, it was exceedingly difficult to prevent or run down these infractions.

One well-remembered incident, however, concerns not a Filipino, but a young and lusty American non-com; his imagination inflamed by soft, dark eyes, flashing smiles and gentle curves; who commandeered one merchant's entire supply of what medical officers refer to, delicately, as "prophylactics".

However, we did try to keep, and in the main succeeded in keeping, an accurate record of all personal property requisitioned. But because Captain Britton, who took over the Quartermaster job, died as a prisoner of war and the records were lost, the owners have had a difficult time collecting.

CHAPTER III - A BLACK CHRISTMAS

Crew of crashed B-17 bomber, attach to 61st Field Artillery, arrives in regimental headquarters Cabatuan Iloilo

A week after the initial bombing of Iloilo on 18 December, we had unexpected visitors. Six of the few remaining B-17's from Clark Field, which were now based at Del Monte, Mindanao, had taken off 14 December to attack the Japanese landing forces at Legaspi, Luzon. Due to mechanical difficulties, only three succeeded in getting through to the target area, and there encountered a heavy concentration of Zeros. Dropping their bombs hurriedly, but with what they believed to be salutary effect, they promptly lit out for home, but not before they had been badly mauled.

One of the fortresses soon managed to elude its pursuers in a thick cloud; another, piloted by Lt. Hewitt T. Wheleas, skimmed treetops and waves all the way back to Mindanao, where he crashlanded in darkness on the beach, with two motors gone, his radio system destroyed, many control cables severed, three of his crew seriously wounded and the radio operator dead. Wheleas was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for this performance.

The third bomber, piloted by Jack Adams, badly shot up over the target, went into a power dive toward a promising-looking cloud-bank hoping to shake off the half-dozen Zeros clinging to his tail. Attempting to level off at 4000 feet, Adams found two of his engines gone and the controls useless. Land was coming up -- fast! There was little choice between rocky beach and forest, until at the last minute a tiny rice-paddy cushioned their crash-landing. Fortunately, none of the crew were too badly wounded to run, and they made the shelter of the woods just before the one persistent Zero who had followed them down made scrap metal of the fortress.

They had landed on Masbate, a small island due south of Luzon. The natives, happy at this opportunity to express their appreciation to the Americans, showered these unfortunate airmen with hospitality to the limit of their resources.

The fliers searched for several days to find an adequate boat in which to try to reach Mindanao. Finally, with the help of Mr. and Mrs. Barney Faust -- originally of Sarcoxie, Missouri -- who operated a Gold mine on Masbate, they located a banca in which some Filipinos agreed to ferry them across Jintotolo Channel to Panay.

The trip was made at night, in order to avoid Japanese patrol craft, and the mine fields were threaded by the simple native device of having one Filipino hang half-overboard in the bow of the boat and watch for them!

Landing on the beach near Capiz in the gray dawn of 22 December they were mistaken by the nervous outpost for an enemy scouting party and promptly "captured" and escorted to Lt. Col. Thayer's headquarters. There Adams told his story and the party was directed to proceed to General Chynoweth's Division Headquarters at Santa Barbara, where they were made as welcome as the very

| *Chynoweth promoted to Brigadier General, 19 December 1941. Also Sharp, Vachon and Fort. |

limited facilities permitted. In addition to Lt. Adams, the pilot, there were Lt. Bill Railling, co-pilot, Lt. Harry Schreiber, navigator, and four enlisted crew members -- Bill Manners, McLean, Paul Raimer, John Fleming. There being no immediate possibility of transportation to Mindanao, the Division Commander assigned the entire party to the 61st Field Artillery.

The following morning (it was Christmas Day, 1941), a young American reported to me at my headquarters. I remember that I was going over some rather bothersome supply matters with Lt. Lapastora, the supply officer, and barely glanced up from the papers before me. His statement that he and six other Americans had been attached by General Chynoweth to the 61st Field Artillery prompted me to look up. Such a Christmas present certainly merited my undivided attention. I saw standing before me a rather handsome, well-set-up chap, and my eyes focused immediately on his embroidered insignia of rank. They were eagles. I remember the shock and the feeling of dismay that swept over me. I was a lieutenant colonel and remember thinking "Well, old boy, it looks like you lose your command". Anyway, I stood up quickly and said, "Won't you please sit down, Colonel, I am at your service".

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: The headquarters of the 61st Field Artillery Regiment, which Col. Tarkington commands, is located in Cabatuan, Iloilo at this time. |

A genuinely sheepish grin came over his face as he replied, "I'm not a colonel, sir. This is one of General Chynoweth's old shirts. I'm only an Air Corps master sergeant -- member of Lt. Adams' crew. We were shot down over Masbate. The three officers and other three men will be along any moment now".

These boys had no clothing except that on their backs when their plane crash-landed and all were wearing a varied assortment of apparel, either loaned or donated by American officers with Division Headquarters, while their own was in the process of having ten days' sweat and dirt laundered out.

We literally took them to our hearts and attempted to make them comfortable with our limited means and facilities. They were all fine men, eager to be of assistance. Each of my battalions gained an American officer and enlisted man -- intelligent and responsible. I kept the "colonel-sergeant" with regimental headquarters. They were Air Corps, yes -- but willing to cope with the ground soldier's life, they were a veritable Godsend and rendered inestimable service in looking after many of the thousand-and-one problems which constantly beset us.

These men were the first contact with anyone outside our island perimeter since the beginning of the war, and the news they brought of conditions elsewhere in the Islands was not encouraging. The radio broadcasts had been consistently optimistic. These men told a different story.

On 12 December the motor-ship Samal arrived in Cebu from Manila with a consignment of sorely-needed signal equipment, rifle and artillery ammunition and eight 2.95 guns. These guns, which were without sights or sight-shanks, fuze-setters or range tables, constituted the only artillery ever received in the southern islands -

the Samal was the last supply ship to succeed in running the Jap blockade from Manila. All eight guns were sent on to Mindanao but the small arms ammunition was distributed throughout the Force, a few cases of it being received shortly before Christmas on Panay.

Col. Tarkington, 61st Field Artillery, brings Corporal Wollman to his headquarters in Cabatuan, Iloilo

About this time, in order to provide more accessible storage facilities for another small shipment of ammunition which had come in from Luzon a week or so previously, a Divisional ammunition dump was established near, and just north of, the road connecting Santa Barbara and Cabatuan, about midway between the two barrios. This dump, being located within the 61st Field Artillery area, was placed under the regimental commander's immediate supervision, but apparently full cognizance of this arrangement had not reached all concerned.

The senior of the two Ordnance, non-coms who had accompanied the meagre consignment of ammunition to the Island, Corporal Paul Wollman, was designated as custodian and warehouseman. His assistant was red-headed Corporal Michalik. both were gluttons for work and each apparently had an inflexible conscience insofar as accounting for their precious cargo was concerned.

Wollman also had an uninhibited distrust of the Filipino, particularly if he wore the insignia of an officer. Misunderstandings immediately arose between him and the Divisional Ordnance officer as to their individual responsibilities, with the result that Wollman succeeded, with strong words and unmistakable gestures, in maintaining his personal point of view. The Filipino was also attempting, conscientiously, to carry out the functions of his office by playing watchdog over the treasure.

The unfortunate angle to the entire situation lay in the fact that the feud came to my attention through Division Headquarters. The Division Commander called me by telephone from his command post at Santa Barbara. From his tone it was apparent that no discussion of the matter was indicated. Wollman had gone too far -- he was to be immediately placed in arrest, by me personally, for disrespect and intimidation of an officer, said General Chynoweth. This was a serious charge.

I had learned to respect Wollman for his strict interpretation or responsibility. His observances of military customs in our few contacts had been impeccable. It was with considerable reluctance, therefore, that I set out to accomplish the mission of carrying, out an arrest on this unsuspecting soldier. Furthermore, it was raining -- not gently but tropically -- as I left my car on the paved road and plodded off through the mud and the Stygian blackness. All was quiet except for the splashing of the rain and the occasional complaint of the gheko lizard. My flashlight failed, and I stumbled on through the abandoned farm debris leading to the loft quarters of the two Americans.

The noise of my arrival had awakened them and they were sitting on the edges of their bunks.

"Do you have a light in here?" I asked. "Who are you?" was the reply.

"Corporal Wollman", I said, "This is Colonel Tarkington. Light up!"

"Yes, sir!"

I waited until the feeble gleam of a candle struggled to dispel the heavy blackness. They were both standing now.

"Corporal Wollman, get dressed, pack your personal belongings. You're going with me. Corporal Michalik, you remain here in charge. Just a little word of advice -- any difficulties you encounter will be reported to me, at once."

I smoked a cigarette while I waited for Wollman. He slung his musette over his shoulder. "I'm ready, sir", he said, and we started out. He restrained his curiosity and remained silent throughout the ride to Cabatuan. There were no extra bunks at our quarters, so we made him comfortable atop a mess table (which was about as comfortable as the bunks were anyway.) I gave him a stiff drink of liquor and told him we'd go over the situation in the morning. I didn't feel in the mood to further disrupt his night.

The following morning, after an early breakfast, I took him aside and acquainted him with the charges and with the fact that he was to be placed in confinement in the barrio jail at Santa Barbara. He was quite shaken by the charges, but defended his actions in refusing to honor an oral order for the withdrawal of ammunition, even while admitting that his conduct toward the Ordnance officer had not been in accordance with the customs of the Service. He confided that his personal dislike for this particular individual

had colored his behavior. I took Wollman to Santa Barbara and personally turned him over to the jailor, with instructions as to his food and treatment. Then I went immediately to the Division Commander to report that his orders had been carried out.

General Chynoweth gave further vent to his ire, that a non-com should so conduct himself toward a commissioned officer as to disgrace the uniform and jeopardize the traditions of the Service. Furthermore, the question of loyalty, trustworthiness and devotion to cause were involved. It was shameful conduct, and merited the direst punishment, said he. Wollman would be tried promptly and punished according to the Court's judgement, the General had decided.

We discussed the case at some length, and finally General Chynoweth agreed, not too reluctantly, I believe, to my request to parole Wollman into my custody and assign him to my unit. I'm sure that neither Chynoweth or myself ever regretted this solution. Certainly I never did, because Wollman was later to become one of the staunchest cummissioned officers on my staff in the 61st Field Artillery.

S.S. Panay sinking

Ever since the first shipload of arms and supplies destined for the Visayan-Mindanao Force had gone down in Manila Bay in the first few days of the war, Headquarters in Manila had been promising to send more to replace those lost on the S. S. Corregidor.

Just before Christmas we were advised that the S. S. Panay was being dispatched to us with ammunition, both rifle and artillery, a couple of old sea-coast guns, gas masks, tentage and various other supplies:

Genl. Chynoweth, Iloilo City, Iloilo.

For your information following radio received quote Commanding General Visayan Mindanao Force: Small arms ammunition comma trench mortar ammunition comma artillery sights and artillery for sixty-first and eighty-first will be forwarded in earliest shipment possible to arrange Stop Shipment will be temporarily delayed Stop Will advise you of date of departure End Signed SEALS unquote

SHARP

Commanding

Again our hopes soared. Maybe this time we'd be lucky!

Long before this, of course, the Japanese were in complete control of air and sea, so the inter-island skippers resorted to the scheme of running only at night, blacked out, and hiding during the daylight hours in some secluded cove, in order to escape the constantly probing enemy ship and plane patrols.

Following this plan the Panay crept out of Manila Bay safely and just at dawn her second morning out slipped into Maricalom Bay on the almost-deserted southwest coast of Negros. Her skipper scanned the brightening sky anxiously. He would have been safely

hidden at anchor an hour ago, but for the fog and rain which had delayed him. Just a few minutes more now, and his ship would be safe -- for the day, at least. Just a few minutes more ------. Was that thunder again?

No, por Dios! Planes!

A squadron of enemy bombers roared out of the overcast. The little ship huddled helplessly on the grey water as the planes swooped for the kill like hawks on a farmyard.

The Panay's armed guard did their noble best, but ten .30 caliber rifles are no match for a bomber's fire, however valiant the riflemen, and in an exceedingly short time the tumbling waters of the Bay were closing over the decks, quenching the fires started by bombs and incendiaries.

Happily for the crew, the ship sank quite close to shore, and in comparatively shallow water, a considerable portion of her masts protruding above the surface even as she rocked gently on the bottom. Unhappily, however, this portion of the Island of Negros is (according to report) infested with a particularly deadly form of malaria, and is therefore virtually uninhabited. It was with considerable difficulty and no little hardship, therefore, that the return to civilization was eventually accomplished by the entire ship's company.

When word of this second sinking reached our headquarters, gloom spread like a pall. We were desperate for supplies -- ordnance especially -- and it began to look as if the enemy held all the aces in this game.

We could hope for no more ordnance from Luzon. The few troops there were too heavily engaged with an ever-increasing enemy foroe, whose effective blockade was slowly but surely strangling the supply of essential materials to the defenders. Our hope for additional weapons hit bottom with the Panay.

In the discussion of this loss among ourselves someone remarked that it would be a beautiful Christmas present if we could cheat the Jap of his kill, recover this cargo and use it against him. I doubt if any of us, privately, could refrain from comparing the approaching Christmas season with those we had known at home. There would be no brightly-wrapeed packages this year, none of the usuel trappings of the holiday season. But worst of all, from a personal standpoint, was the confusion in shipping which had resulted in little or no delivery of personal mail even before war broke. Mail was decidedly spasmodic and uncertain. For many, these anxiously awaited messages were conspicuous by their absence. I've often wondered what happened to the many letters and cablegrams so hopefully and confidently sent, which were never received.

But however gloomily we might view the imediate future personally, none of us admitted the depths of our depression to each other. The situation was too critical for us to dare give in even to that extent. And we hadn't seen anything yet!

I recall wondering why salvage operations were not immediately undertaken on the Panay before the corrosive sea water could render these supplies useless, but in spite of the fact that the ship rested in shallow water, and comparatively aloes to shore, it was not until about the middle of January that General Sharp decided to initiate salvage operations, and a self-styled "expert" was sent up from Force Headquarters to conduct the operations.

Before the war this man had been a very successful traveling salesman for a Manila concern, since in one respect he was a bona fide expert -- he could "sell" himself. He was a very convincing talker, and the assumption is that he "sold" himself to General Sharp as a salvage expert, for he apparently knew very little about it. After some weeks of haphazard efforts, during which little of value ran accomplished, this "expert" withdrew, or was withdrawn.

A short time after this, General Chynoweth called on Colonel McLennan, the Navigation Head Officer and local commander in Iloilo, one morning and stated that since it was his understanding that the salvage operations conducted by General Sharp's headquarters had been unsuccessful, he would like to see if anything further could be done about it, inasmuch as the need for the ordnance in the cargo, especially, was so critical. Accordingly, a representative of the Visayan Stevedoring Company, a Spaniard by the name of Zadero, was sent down to look over the situation. Zadero, who was a real expert in this line, reported back to McLennan in a few days that the job appeared to be not too impossible, and that all the necessary equipment was readily available except that he did not have an air compressor, nor -- and more important -- did he have a diver.

McLennan knew of an air compressor which could be acquired, and had the diver -- whom he was exceedingly anxious to be rid of. He was a half-pint-sized Swede who had appeared in town one day from God knows where, carrying a gun and an insatiable thirst. He had promptly undertaken to relieve the thirst with such vigor and abandon as to bring him, very shortly, to the attention of the local gendarmarie, whose first action was to relieve him, over his violent and sustained protests, of his gun.

The Filipino police had a tendency to handle a white man with a bit more respect than an ordinary run-of-the-mine drunk, even if he happened to be considerably drunker, which this little Swede was. As soon as he was reasonably sober they brought him before McLennan. After discussing his transgressions for some time with the culprit, who of course promised faithfully "never to do it again". McLennan asked for, and obtained, his release. In a matter of hours the Swede was blissfully drunk again and back in the hoosegow, from which, after letting him cool his heels for a few days, McLennan again extracted him. Again he tried to drink the town dry and again tangled with the police, who by this time were beginning to be a trifle bored with the situation, as was McLennan. It would be hard to estimate just how many times this performance was repeated, but when the need for a diver arose, he was either in the calaboose cooling off, or just out and about to be in again.

McLennan spoke to Zadero about him, and discovered that he knew the inebriate quite well, Further, it developed that the little fellow had been doing diving jobs around the Islands for

years and was really an excellent diver. His one weakness was liquor, but Zadero assured Mac that it he could get the fellow to Maricalome Bay the liquor problem would be ended, for there wouldn't be any liquor within miles and miles and MILES of the place. They sent for the Swede (the local police knew exactly where he was, and extracted him from one of the better-supplied bars) and offered him the job. He accepted and Mac turned him over to Zadero, with a sigh of relief.

Word was sent to General Chynoweth's headquarters that everything was set, but due to some malfunctioning at his headquarter, his approval was delayed for several days, which interim the Swede spent getting gloriously stewed again. Zadero, as his protector, could keep him out of jail, but could not keep him sober. When Chynoweth's approval was received and the contract signed, the diver was poured on board and the expedition sailed, with Zadero in command and no liquid stronger than coffee aboard the ship.

In addition to the diver needed to open the hatches of the sunken ship and load the cargo into slings for hoisting, considerable labor was required to operate the winches, handle the cargo once it was ashore and attempt to recondition it. This detail of about 25 Philippine Army enlisted men was in charge of Captain Don Amend. The work went very slowly, since only the one diver was available, but eventually the deck was cleared of the debris resulting from the bombing, the hatches were opened, and the cargo began to come up.

The first items encountered were gas masks, thousands of them, and none of them worth a damn. The canisters were soaked and as a consequence all of the chemicals which were supposed to absorb gasses had long since been in solution. The satchels, in which the mask, canister and tube were carried, were in not too bad shape, but there was no use for satchels. However, since the masks were on top of the load they had to be removed before any of the other cargo could be reached. Under the masks were bales and bundles of shelter-halves, tarpaulins and the like, while the field pieces, machine-guns and ammunition had been loaded, according to proper procedure, on the very keel.

All of this critically-needed equipment was now in very sorry shape, The ammunition, of course, oculd not fire, but it was found that by emptying the shell completely and exposing the entire contents to the sun for a couple of hours, then replacine the dried powder and the bullet and recrimping, that approximately 75 peroent of the stuff would fire. Its ballistic qualities were in grave doubt, but at least it would go "bang!" and the bullet would get out of the muzzle of the piece. How much farther it would go was never definitely determined, but there was serious doubt that the distance was great.

The one indispensable element in this reconditioning process was the hot, tropical sun. Consequently this work could be accomplished only on sunny days, and even then only during the hours when the sun was at its height. Admittedly this process left much to be desired, but it worked -- up to a point.

Attempts to dry out the ammunition by means of the heat from a fire invariably resulted in an explosion. Possibly there was some degree of heat at which this might have been successful, but it was never discovered, for the experiment was discontinued for fear the entire supply of ammunition would be expended in trying to determine it.

The machine guns and field pieces had suffered even more, the finer steel parts, usually springs,, being completely rusted out by the salt water. The machine shops throughout the Visayas were busy right up to the moment of surrender trying to fashion satisfactory replacements for these springs. In the case of the machine guns there was reasonable success, in that about half-a-dozen were gotten into what -- it was hoped -- was operating condition. They would shoot, but how long they could have been kept in action with their home-made parts was quite another question. The field pieces, 2.95 mountain howitzers, were a greater problem. Their breech mechanism originally contained some rather complicated spring made of a higher grade steel than was available at this time. Continuous efforts were made to construct satisfactory substitutes, but up to the moment of surrender none had functioned satisfactorily. Since those were the only artillery pieces in the Visayas it was never possible to test the artillery ammunition which was recovered, but it would probably have been no better than the rifle ammunition, and the reconditioning of it, had it been possible, would have been a much more complicated task.

The entire salvage operation had progressed so slowly, due to the various handicaps, that although it was begun the latter part of January it was the middle of April before the ordnance began tO come up, so that no great strides had been made with its reconditioning before the surrender put an end to such experiments.

CHAPTER IV - "BAUS AU"

The invasion of the Davao area in Mindanao a few days before Christmas had apparently caught General Vachon short of ammunition also, (although he did, at least, have a few 2.95 mountain guns for his artillery regiment) for General Chynoweth now reoeived orders to ship to Vachon half of the rifle ammunition and all of the artillery ammunition on Pansy. Having no artillery pieces, and only the faintest hope of ever getting any from the sunken steamer, the loss of this ammunition was not too important, but to part with even half of our meagre supply of rifle ammunition was a wrench. However, at the moment, Vachon needed it worse than we did, so off it went (except for the 1500 rounds of artillery ammunition in the 61st Field Artillery magazines, which was overlooked) with our fervent prayers for its safe arrival. This time our prayers were answered.

Baus Au

For some time past, all of us on Panay had recognized the impossibility of defending the beaches in the event of a major enemy invasion, as called for in the original War Plan, and preparations were under way, without official sanction from Manila, to enable us to make a sustained stand in the mountain masses, to which we planned to retire after as prolonged a delaying action as possible.

On Christmas Day, General Chynoweth received two messages -- one from his family congratulating him on his promotion to brigadier-general, which he had reoeived on 19 December -- and the other from General Sharp oontaining copies of instruotions from General MacArthur. This message from General MacArthur was our first knowledge (other than radio reports, which had been consistently optimistic) of the trend of events on Luton. MacArthur stated, in effeot, that his troops were fighting with their backs to the wall, and directed that if we were cut off from contact with Headquarters on Luzon we should continue to keep a locus of American-Filipino resistance on each island.

This was more depressing news, of course, yet we were glad to know that MacArthur realized the impossibility of carrying out the original War Plans, and it gave the stamp of his approval to the practicable solution which General Chynoweth had already formulated.

The mountain area of Panay, which for the most part is extremely rugged, had been divided into regimental sectors. The movement of food and supplies back into these mountains was now intensified. "Baus Au", the slogan coined by Lt. Col. Fitzpatrick, oommanding the 63rd Infantry, became the whip. "Baus Au"--the Filipino phrase meaning "Get it back!" It characterized the project, which became known as "Operation Baus Au".

All units were engaged in this operation in their own prescribed zone of action. The 61st field Artillery was no exception. The food and supplies being carried up into the mountains would be securely hidden in small caches scattered over wide areas, to furnish the sinews of maintenance for the nuclei of

American military resistance, as MacArthur had directed. Given sufficient bases of this kind we would be enabled to sustain guerrilla operations almost indefinitely, even in the event cf a major Japanese occupation of the Island.

This packing in of supplies was gruelling work, since these trails are passable only on foot--and I uae the word "passable" loosely! I have seen, and clambered over, places along those rock walls that would scare the horns off a mountain goat. Yet those tiny Filipinos planted their bare feet with prehensile toes, on the narrow ledges and never missed a step.

The civilian populace was quite uneasy over our change to these guerrilla tactics. Many of them never did understand the reasons for our planned withdrawal into the mountains. They took great pride in their Army, and having been indoctrinated for years with the idea of American invincibility, were all for falling on the enemy tooth and nail and hurling him back into the sea. Which was a fine idea -- we'd have liked nothing better. But with our paucity of equipment and trained personnel even to have attempted such action would have served no purpose and could have resulted only in the mass butchery of our troops.

When and if we were forced back into the hills by Jap invasion, our troop strength was to be cut down from regiments and battalions to small bands of stalwarts. These few were to be picked for their physical stamina, their courage, their loyalty, and general soldierly aptitude. The others were to be discharged when we reached the foothils. They would turn in all arms, ammunition and equipment issued to them and return to civil life. Caches for this equipment had been selected and prepared. Only those who had been chosen as the eventual "Robin-Hooders" were employed in moving supplies into the mountain areas. No others were to know the whereabouts of the supply caches, since the lives and effectiveness of such a band must depend upon individual and collective secrecy and loyalty.

Mountain fastnesses were being reconnoitred and the selected troops being intensively trained in guerrilla tactics. It was vital that every officer and soldier should know every trail, every stream and barrio like the palm of his hand. We must be capable of striking with fury and vanishing into thin air.

Lewis and I alternated, usually, in supervising "Baus Au".

|

Note from Ronnie Miravite Casalmir: When one comes across the term "Baus Au," one cannot help but wonder what language or dialect was it? That's me included. And I've been asked by others as well.

Upon dissecting further the "There Were Others," I realized that Father Tavarro was correct. The slogan "Baus Au" was said to be coined by Lt. Col. Fitzpatrick, commanding the 63rd Infantry, and this 63rd Infantry regiment was activated or mobilized on Romblon Island. Clearly, Lt. Col. Fitzpatrick must have gotten the term from his men who are natives of Romblon. The mountain area of Panay, which for the most part is extremely rugged, had been divided into regimental sectors. The movement of food and supplies back into these mountains was now intensified. "Baus Au", the slogan coined by Lt. Col. Fitzpatrick, commanding the 63rd Infantry, became the whip. "Baus Au"--the Filipino phrase meaning "Get it back!" It characterized the project, which became known as "Operation Baus Au". Baus Au Colonel Chynoweth drove immediately to the airfield, and found a scene of utter confusion. Shortly before noon, a battalion of the 63rd Infantry which had just been mobilized on Romblon Island, had landed at the dock, with orders to move inland immediately. Instead of proceeding, as ordered, they had stopped at the airfield to have lunch and were caught like sitting ducks as the Japs swept over. Japanese bomb Iloilo City The 63rd Infantry regiment was initially commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Albert F. Christie upon its activation in October 1941 in Romblon. However, then Colonel Bradford Chynoweth the newly designated commander of the 61st Infantry Division selected Christie as his division Chief of Staff. He was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Carter McClennan as its commander in late November. It was inducted to USAFFE on November 15, 1941. Training and organization was still on going when World War II in the Philippines started in early December 1941. The regiment was ordered to transfer to Panay Island. The island was subject to aerial bombardment on the day it arrived in Panay, after forces in Luzon retreat in Bataan. On January 1, 1942, General Sharp ordered General Chynoweth to send 61st and 62nd Infantry regiments and the 61st Field Artillery to Mindanao, leaving only 63rd Infantry as its combat unit in the island. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/63rd_Infantry_Regiment_(PA) |

Lieut. Col. John L. Lewis at Cabatuan to keep up impetus of regular training activities

In Memory of Lieut. Col. John L. Lewis

In Memory of Lieut. Col. John L. Lewis

|

He pulled a serious expression over his infectious grin. "Colonel Tark, Wald and I ran across some real G-2 today. We've talked it over and we've decided that you haven't taken one bit of time away from your command since this thing began. We kinda think you're due for a little entertainment".

"What's G-2 got to do with time off and entertainment?" I questioned.

"We figured you're entitled to a little recreation -- maybe you wouldn't be such a damned grouch if you'd do a little carousin'", he grinned.

"Buck, you're a reprobate. what are you driving at? Come on, now -- spill it -- that's a command!" I replied. "But wait before you pull the lanyard -- another small divident so I can take the shock standing!"

It was plainly apparent that they had concocted some sort of a lark. I took a sip from my replenished glass. "Now, you'd better let Wald talk. He seems to want to get to the point".

"It's just this", Wald said. "We've got a reliable tip on a damn' swell cabaret in full swing behind blackout curtains down in Iloilo".

"That's fine", I retorted. "You two go ahead on down. You're all slicked up and polished. and besides, there'll be no more than two of the five Americans away from this post tonight."

"But wait a minute", Lewis broke in. "If the Colonel doesn't go, no one goes -- you need it!"

"Nuts! Buck, I'm tired and dirty, and besides, I'd better stick around."

"Nothin' doin'", he objected. "We've decided you're going. So now on with your bath and yourself pretty for tne gals.

"Everything's quiet and under control. Price, Wald and Murphy will stay. I'm going with you, so get on your horse".

The upshot of it was that I went. It was too enticing to miss. Buck and I drove down to Ilo through the starlit night on the first non-official venture since the Japs ruptured the peace of the Orient. I felt uneasy about leaving the command, and I knew Buck wasn't too comfortable, either, but his usually ebullient spirits dominated the situation and we were soon engaged in an intensive search for the blacked-out cabaret.

We were not over-familiar with Iloilo, but after some cruising about discovered a knot of people loafing in front of a rather pretensious-looking establishment, and upon inquiry, discovered that we had arrived.