4.1 Guerrilla Organization

Prior to the Joint Punitive Expedition in Panay, Captain Watanabe’s information section distributed confidential papers on the guerrilla organization and situation of the Philippine Army and resisting civilian government to all officers concerned. The outline of the information was as follows:

Tomas Confesor, the great political leader, established civil government in Iloilo province on May 8, 1942. He had divided Panay into administrative districts as follows under deputy governors. Iloilo (Cesario C. Golez, Fernando Parcon) Capiz (Cornelio Villareal Sr.) and Antique (Tomas Sartaguda).

|

13. Organization of the Civilian Government in Panay and Romblon Islands (As of October 1943)

Governor Tomas Confesor, Civilian Government in Panay and Romblon

Deputy Governor of Iloilo Fernando Parcon

1st District Mariano Benedicto

2nd District Ramon Tabiana

3rd District Patricio Confesor

4th District Juan Griño

5th District Afelardo Apotadera

6th District Cesario Golez

7th District Benjamin Griño

8th District Jose Aldeguer

9th District Carlos Soriano

10th District Epiphano Montero

Deputy Governor of Capiz Cornelio Villareal

1st District None

2nd District Cornelio Villareal

3rd District Pedro Fuentes

Deputy Governor of Antique Tomas Sartaguda

1st District Ramon Masa

2nd District Simeon Medara

3rd District Jose Mendoza

EPG (Emergency Provincial Guard)

Dept of Publicity/Information

Dept of Finance

Dept of Accounting and Audit

Dept of Health

Dept of Food

Dept of Consumption/Supplies

Note: Under the Deputy Governors were 3 or 4 town mayors (municipal, district); and under the mayors were village heads (barrio teniente [lieutenant] or capitan [captain]). Each town had a 'Bolo Battalion' or Home Guard as vigilantes.

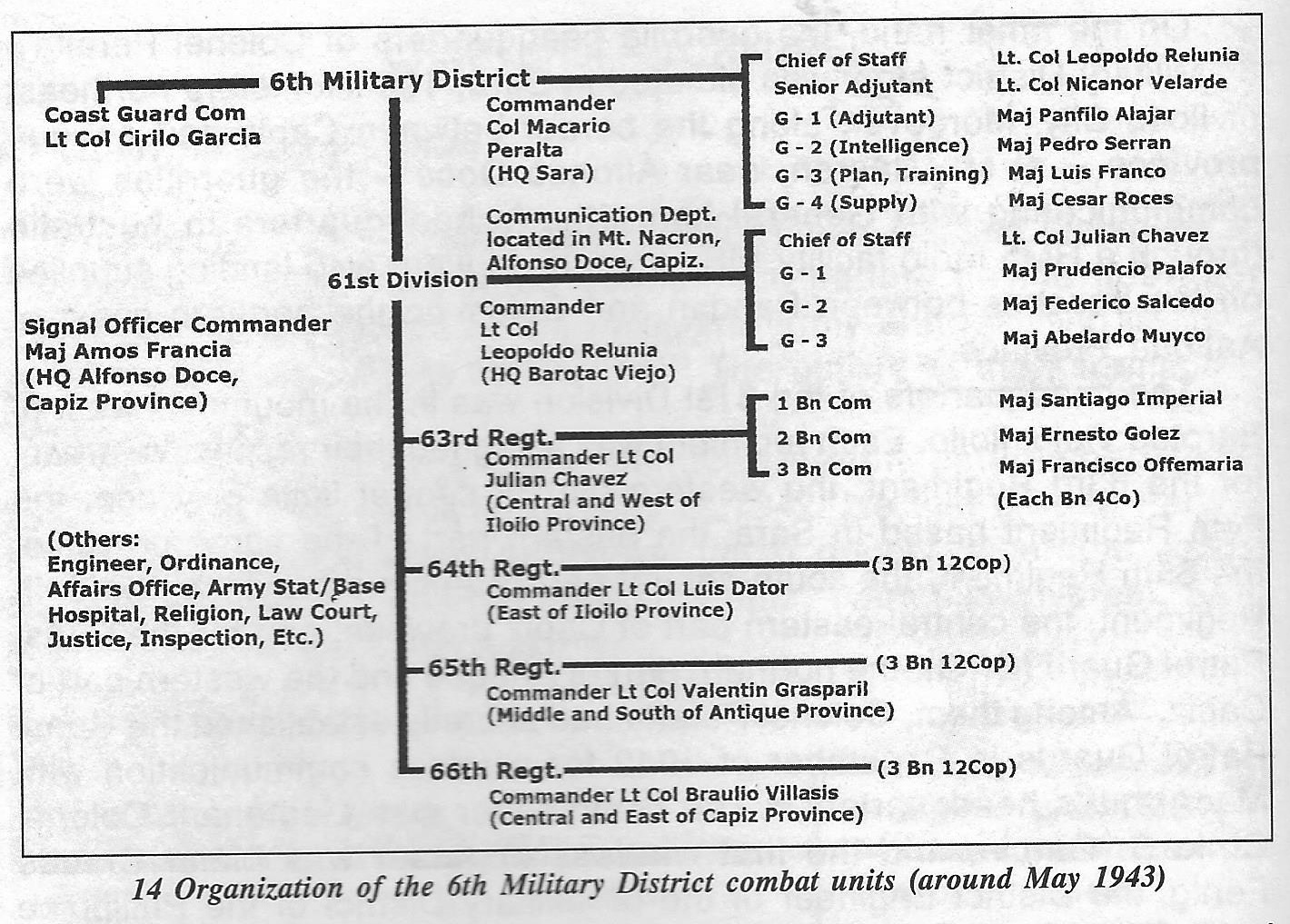

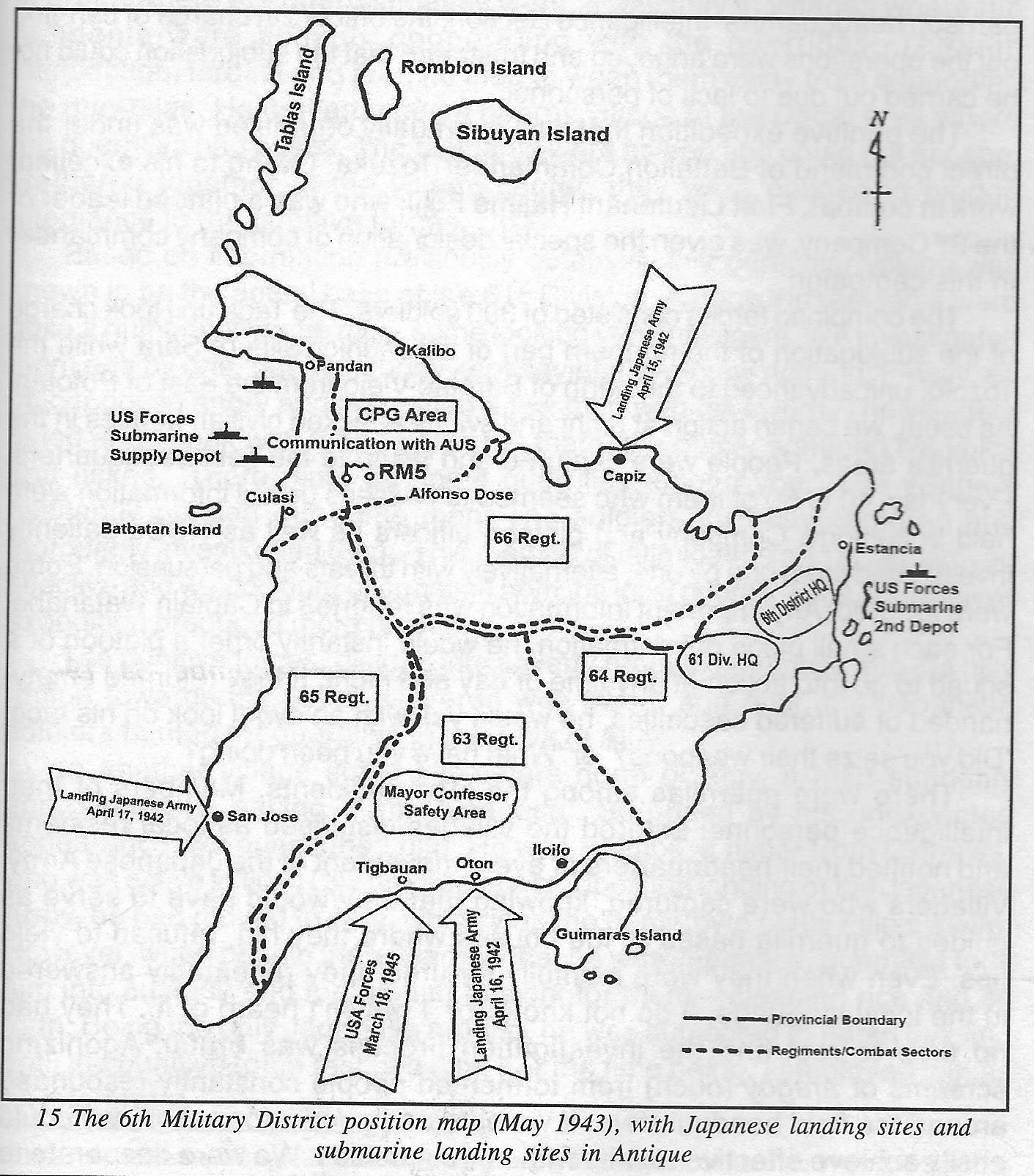

On the other hand, the guerrilla headquarters of Colonel Peralta’s 6th Military District army was situated in Sara, 100 kilometers northeast of Iloilo City. Moreover, along the border between Capiz and Antique province – at Mt. Nacron, near Alfonso Doce – the guerrillas were communicating with General MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia through a RM5 radio facility. US submarines were also landing supplies on the beaches between Pandan and Culasi on the northern coast of Antique Province.

The headquarters of the 61st Division was in the mountains west of Barotac Viejo, Iloilo. Each regiment was assigned their respective areas: for the 63rd Regiment: the western part of central Iloilo province; the 64th Regiment based in Sara, the eastern part of the same province; the 65th Regiment, the south-central part of Antique province; the 66th Regiment, the central-eastern part of Capiz province; and for the Coast Patrol Guard (CPG), the northern part of Antique and the western part of Capiz. Among them, Colonel Peralta had secretly established the Coast Patrol Guards in December of 1942 for wireless communication with MacArthur’s headquarters. The commander was Lieutenant Colonel Cirilo B. Garcia, and the first wireless engineer was Major Claude Fertig, the District Engineer of the 6th Military District of the Philippine Army.

Although we did not grasp the precise number of the personnel and equipment of the guerrilla forces, we presumed them to have numbered around 15,000. This was according to the intelligence we received from various sources.

|

14. Organization of the 6th Military District combat units (Around May 1943)

6th Military District

Commander Col Macario Peralta (HQ Sara)

Chief of Staff Lt. Col Leopoldo Relunia

Senior Adjutant Lt. Col Nicanor Velarde

G - 1 (Adjutant) Maj Panfilo Alajar

G - 2 (Intelligence) Maj Pedro Serran

G - 3 (Plan, Training) Maj Luis Franco

G - 4 (Supply) Maj Cesar Roces

61st Division

Communication Dept. located in Mt. Nacron, Alfonso Doce, Capiz

Commander Lt Col Leopoldo Relunia (HQ Barotac Viejo)

Chief of Staff Lt. Col Julian Chavez

G - 1 Maj Prudencio Palafox

G - 2 Maj Federico Salcedo

G - 3 Maj Abelardo Muyco

63rd Regt.

Commander Lt Col Julian Chavez (Central and West of Iloilo Province)

1 Bn Com Maj Santiago Imperial

2 Bn Com Maj Ernesto Golez

3 Bn Com Maj Francisco Offemaria

(Each Bn 4Co)

64th Regt. --- (3 Bn 12Cop)

Commander Lt Col Luis Dator

(East of Iloilo Province)

65th Regt. --- (3 Bn 12Cop)

Commander Lt Col Valentin Grasparil

(Middle and South of Antique Province)

66th Regt. --- (3 Bn 12Cop)

Commander Lt Col Braulio Villasis

(Central and East of Capiz Province)

Among those who joined the guerrilla movement were intelligent and highly patriotic men from universities or high schools. There were, however, thieves, robbers or gangsters who had joined the guerrilla forces because they wanted to eat. In the confusion of battles, the latter group broke into civilian houses, robbed the people of money and articles, or committed violent acts on women. When the parents or brothers of the victims protested against them, guerrillas often labeled them as Japanese collaborators and publicly lynched them. Some town leaders surrendered to the Japanese Army because they opposed these criminal actions of the guerrillas.

As the lawlessness of some guerrilla soldiers increased, local people protested to Governor Confesor through the leaders of their villages and towns. Confesor referred these matters to Colonel Peralta, who, in turn, strengthened the organization of the local Military Police (MP) to subdue these wrongdoers. However, chaos prevailed as soon as the punitive expedition of the Japanese started. Since despicable guerrilla members were able to do what they wished, the confrontations between the Confesor and the Peralta groups became more severe.

In May 1944, a Filipino spy told me that local residents desired to be able to drive off the Japanese Army. However, they were more fed up with lawless guerrillas and their crimes and, thus, hoped that the US Army would arrive as soon as possible so that peace and order could be restored.

It was easy for some of these guerrilla atrocities to be blamed upon Japanese soldiers. At the post-war War Crimes Tribunal, some wrongful letters of complaints and witnesses against Japanese soldiers submitted by the Philippine Army were rejected by the court.

#Start of Punitive Expeditions

4.2 Start of the Joint Punitive Expeditions in Panay (July 7 to December 31, 1943)

In June 1943, a new staff officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hidemi Watanabe, was assigned to the Visayas garrison headquarters at Cebu. On his way from Tokyo, he passed by Manila headquarters for general instructions on the subjugation of the Visayas area. The garrison headquarters staff was rigorously instructed to crush the Panay guerrillas completely. This was due to the latter’s attack on and the resulting humiliation of General Tanaka.

Soon after his arrival in Cebu, Colonel Watanabe came to Panay for inspection. Colonel Watanabe chose Captain Kengo Watanabe, a highly regarded officer among the staff, as his right-hand man. Immediately, the colonel asked the captain to plan the great punitive expedition in Panay. Garrison commander General Kono left everything about the plan to staff officer Colonel Hidemi Watanabe. In like manner, unit commander Colonel Tozuka put everything in the hands of Captain Watanabe who was the battalion’s Operations and Intelligence chief. Henceforth, the two Watanabes decided on the plans for and carried out the operations of the punitive expedition.

The rainy season had started when, on July 7, the Japanese forces in Panay jointly pursued a six-month punitive expedition. The forces consisted of seven companies chosen from various units, accompanied by kempeis: the Tozuka unit in Iloilo, the Kinoshita unit in Capiz, and the Taga unit in Antique. In addition, the navy gunboat Karatsu, a radio location section, and a landing craft unit from Army Headquarters in Manila were dispatched. The goals of the expedition were the capture of guerrilla leaders, their 15 wireless radios, and the destruction of their bases.

To directly command the operations, Major General Kono and staff officer Colonel Watanabe moved the expedition headquarters from Cebu City to Iloilo City. Colonel Watanabe was inclined to adopt the strategy of competitive operations and usually assigned favorable areas to Captain Watanabe. Hence, there was an apparent competition in the punitive operations between our unit, the Tozuka unit in Iloilo province in the east, and the Taga unit in Antique province in the west.

However, soon after the start of the expedition, we received a distressing warning order from Iloilo Headquarters. About 50 soldiers of the Kinoshita unit were blown up in two trucks at Dumarao, Capiz province.

#Japanese go after Tomas Confesor

Our first target was the assault of Governor Tomas Confesor’s base to capture him and destroy his position. Our punitive forces under Captain Watanabe first attacked the guerrilla base in the jungle northwest off Alimodian, around 22 kilometers northwest of Iloilo City. Nonetheless, the three companies of guerrillas who were there had already evacuated. All the houses were vacant and there was scarcely any inhabitant.

Chasing after the guerrillas, the force arrived at Cagay on their quick advance into Bocari where the civil government of Governor Confesor had its main base. A captured local resident guided us into Bocari. It was an astonishing sight to see. There were mountains surrounding Mt. Inaman (1,350 meters high), the inside basin of which was four kilometers east to west and two or three kilometers from north to south, with a roaring river flowing through the center. On the slopes were rice fields and under the trees were hundreds of houses of the villagers. We checked on the houses but they were all empty. Every day, we interrogated a dozen local residents as well as guerrillas to get information about Confesor, but there was no information forthcoming at all. Nor was there any official of the civil government to be found.

In the mountains, we found and chased down a Filipino family of three. The man killed himself with his pistol; his wife also died of exhaustion and the shock of her husband’s death. We also came across a boy of seven or eight years, from whose story we learned that his father was an important staff member of the Confesor government. Warrant Officer (WO) Fusataro Shin of the Kempeitai sympathized and took the boy with him all throughout the expedition while other soldiers took care of him as well.

During the expedition, we pushed on day and night, covered with mud and sweat. In the end, we had to give up the Bocari operation. We only learned that Confesor had developed some disease of neuralgia or some sort and that he had been carried away in the direction of Antique? We had no news about the printer of their banknotes, Press One. (Later on, we learned that the guerrillas had destroyed the printer of the civil government because of conflicts over financial matters.)

This mission did not produce much direct results. However, the inspections of the heavenly natural fort of Bocari – with its fields of rice, corn, sweet potatoes and other food sources surrounded by mountains – gave us information that would later on be useful for the retreat of the Japanese Army when the US forces on landed Panay towards the end of the war.

4.3 Searching for Governor Confesor

On the way back from Bocari, we learned that there were guerrillas in a village between San Miguel and Alimodian. We surrounded the area during the night and started interrogating each resident early the next morning. Everyone said that there were no guerrillas in the neighborhood. Because of this, we were more at ease but also continued searching.

Suddenly, we heard an enemy light machine-gun shooting wildly nearby and hurriedly reacted. A soldier of the 3rd Company reported to me that Corporal Shiraboshi was killed. I was enraged when I saw his awful corpse. His body was so riddled with bullet holes that it looked like a honeycomb. A soldier reported that Shiraboshi had knocked on a door of a house but it did not open. As he tried to force it open, the guerrilla waiting inside shot him. As he fell, the guerrilla ran away through a window and disappeared. Shiraboshi was a nice and handsome young man who was the machine gun detachment leader when I was in the 3rd Company. Since I knew him well, I felt bitterly sorry for him.

The soldiers who gathered around Shiraboshi were enraged at the sight of his body and started to yell, ‘We were deceived, there are guerrillas among the villagers who are in league with them. We must avenge Shiraboshi’s death.’ Once again, they started to inspect each house, taking into custody any one regarded as suspicious. We interrogated them closely but all of them kept saying they knew nothing about any guerrillas. The outraged Captain Watanabe shouted, ‘Behead those whom you suspect are guerrillas!’. Thus, young men regarded as guerrillas were beheaded one after another. Their heads and corpses were scattered all around.

In another instance, ‘we had been told that the Matsuno platoon of the 1st Company was surrounding a village. Feeling tense from the last encounter with cornered guerrillas, we checked each of the houses as we tightened the net around them. However, the soldiers of the Matsuno platoon did not appear to be operating as a single net. Upon realizing their disorganization, the rest of us lost our composure. Captain Watanabe was furious and yelled, ‘Matsuno, why are you not besieging the village!’ Taken aback, Second Lieutenant Matsuno shouted back, ‘I have gotten no such order!’ This made Captain Watanabe even more irate, and Second Lieutenant Matsuno was severely humiliated in front of the soldiers. ‘Matsuno can be of no use anymore in this punitive action. You should remain at the garrison!’ Since then, Second Lieutenant Matsuno never joined any other punitive expedition, a fact that was to be in his favor. Those men Captain Watanabe considered ‘useful’ were unfortunate as they were sent to the guerrilla fronts and one by one lost their lives.

#Japanese capture the daughter of Patricio Confesor

The first unfortunate ones were members of the 4th Company or the Yoshioka unit. We learned that the Takahashi Company of the Taga unit held captive a daughter of Patricio Confesor – brother of Governor Confesor – and several nurses at the border between Antique and Iloilo provinces. Captain Watanabe judged that Confesor had fled to Antique, which had originally been the area of operation of the Taga unit. Nevertheless, Captain Watanabe wished to capture Confesor himself, and so dispatched the Yoshioka Company to perform this assignment.

The Yoshioka Company was running out of food during their expedition. Parts of the area they went through were unexplored mountainous regions – more than a thousand meters above sea level – as well as low swamps that bred mountain leeches. Local guides were afraid, but the company pushed through mountain after mountain, slurping gruel and munching corn. At the end of July, they managed to reach the Taga unit at the Sibalom garrison of Antique province, about 40 kilometers away from Bocari. Personnel of the Taga unit first thought they were a group of beggars as they were all so ragged, exhausted, and with no proper footwear. When offered a meal, they greedily devoured it beyond all sense of shame.

After a few days rest, the Yoshioka Company was ordered to join the Taga unit that was tasked to carry out the punitive expedition into northern Antique up to the area of Pandan. Pandan was the base where US submarines landed supplies for the guerrillas. Many men of the Yoshioka Company had upset stomachs from the large and sudden amounts of food they had consumed. All the same, they obeyed the order and ran around the mountains and valleys searching for guerrillas in the rainy season which produced not much result. They ended the expedition of northern Antique on September 8 and came back by boat to Iloilo City.

4.4 False allegiance of villages (September 7 to December 31, 1943)

After the punitive operations around the mountains of Bocari and the subjugation of Guimaras Island, the Tozuka unit returned to Iloilo City for a few days’ rest. By around September 7, 1943, another phase of the punitive expedition aimed at the northeastern area of Panay Island started. The target area included the towns of Ajuy, Sara and San Dionisio where Colonel Peralta’s headquarters for the 6th Military District, the 61st Division as well as the main headquarters of the 64th Regiment were located. Other targets were the 661st Regiment and the Coast Patrol Guard [sic.] in Capiz, and Tablas Island, and the 65th Regiment in Antique. These major expeditions lasted until the end of December.

All troops, including the Battalion Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka, were in local clothes and wore hats of woven bamboo or grass. Seen from a distance, it was hard to tell if they were guerrillas or local residents since the officers kept their pistols and swords hidden around their waists. Captain Watanabe and Noriyuki Otsuka of the Intelligence Section were insisting that the punitive operations should be done the American way, expressed in the Filipino proverb that meant ‘After the American soldiers passed, there were no grass, no insects? This view urged the thorough suppression of guerrillas and other islanders.

|

The target areas for subjugation–Ajuy, Sara, and San Dionisio–were well-known agricultural areas that served as a great supply base for the guerrillas. Until then, the Japanese Army had not reached this area, except for support group of the 63rd Line of Communications garrison unit that went through the area in the mopping-up operations in early 1943.

Jose Aldeguer, one of the Deputy Governors of the local civil government, was cooperating with the guerrillas and was leading the local residents there. Hence, in both military and political terms, the area was a haven controlled by guerrillas. Although there was adequate information of this situation at the garrison headquarters’ Intelligence Section, the officers in charge of carrying out the operations were annoyed and frustrated that the subjugation could not be carried out due to lack of personnel.

The punitive expedition that was eventually organized was under the direct command of Battalion Commander Tozuka. Owing to his excellent work in combat, First Lieutenant Hajime Fujii, who was a platoon leader of the 3rd Company, was given the special designation of company commander in this campaign.

The combined forces consisted of 300 soldiers. The Taga unit took charge of the subjugation of the northern part of the municipality of Sara while the Tozuka unit advanced to the north of Barotac Viejo from the east of Pototan. As usual, we began action at night and swiftly attacked civilian houses in the guerrilla areas. People were captured and taken to the field headquarters. Everyday, 40 to 50 of them who seemed to possess useful information were held in custody. Company and platoon officers as well as NCOs patiently investigated them one by one, alternatively with threats and persuasion. Some were tortured. Any important information was reported to Captain Watanabe. For each small piece of information, he would instantly order a platoon or a squad to go into action at any time of day and night. If they returned empty handed or suffered casualties, he would yell with an awful look on his face, ‘Did you seize their weapons?’ or ‘What have you been doing?’

There were guerrillas among the local residents. Members of their intelligence personnel entered the villages disguised as local residents and notified their headquarters of every movement of the Japanese Army. Villagers who were captured, knowing that they would have to serve as guides to guerrilla bases or the houses where they hid, refused to yield tips. Even when they were painfully tortured, they repeatedly answered in the local language, ‘I do not know’, or ‘I haven’t heard of it’. They had no time to rest and the investigation process was brutal. Agonizing screams of aragoy (ouch) from tormented people constantly resounded around the field headquarters. If we obtained good information, we could easily achieve effective results with few casualties. We were desperate to get information, by any means.

From the little information given up by the locals, we knew there was a major guerrilla base in the area of Dacal, northeast of Barotac Viejo. By the time the punitive units were led there, however, the place was already vacant. Throughout this time, the guerrillas had been avoiding direct confrontations with the Japanese Army, hiding their weapons and mingling with the local population. The residents also protected the guerrillas, risking their own lives since members of their own families were among them.

In those days, Captain Watanabe took a harsh stance on the people of areas where the guerrilla bases were, especially in villages where the residents were actively cooperating with the guerrillas. Through intimidation, threats and fear, he tried to wean them away from supporting the guerrillas. He first attacked a nearby village in the Dacal area where the guerrillas had bases. The residents were asleep and could not escape. Gathered together at the village center, they were obliged to pledge allegiance to the punitive forces.

Based on information previously obtained, this particular village was known to be the actual base of the 61st Division. Among the residents were quite a number of young men, some looking very intelligent. We investigated them one by one, but everybody kept saying they knew nothing. Finally, an officer got so angry and beheaded a few men with his sword. The villagers paled and shook with fear. Looking at them, the officer softened his voice–and asked, ‘There must be some guerrillas among you.’ The villagers hesitantly pointed out some men. The soldiers instantly captured and thoroughly investigated them. This method of intimidation and threat proved effective and we got more information from the local people. Thus, the punitive expedition produced more results.

The punitive forces, divided into several groups, advanced into the hilly region towards the south. Covered with sweat and dust, the Japanese soldiers hunted for guerrillas in the area of Ajuy.

In another village some kilometers north of Ajuy, a man suddenly approached us saying ‘I am Japanese’. Surprised by his unexpected was Shimoji, a fisher from Okinawa, was active in lloilo City before the war. Upon the landing of the Japanese as the hometown of his Filipina wife. However, when the people learned that he was Japanese, guerrillas took into custody and forced him to work for them–cleaning rice and so forth. Being the only Japanese around, he was subjected to harsh bullying until the punitive force rescued him. For the time being, I employed him as an interpreter.

As we approached Ajuy, 65 kilometers northeast of lloilo City, the hunt for guerrillas and the investigation of local residents became more and more harsh. After three and a half months of punitive operations, the guerrillas appeared to have been avoiding the Japanese Army. The punitive forces were not able to have any real battles with them and simply wandered around mountains and along rivers searching for guerrilla forces. The guerrillas seemed to have been watching us from a distance but kept away. Captain Kengo Watanabe, who was effectively the punitive force commander, was often irritated seeing our unit in such a situation everyday. The gonorrhea he got in Iloilo City was causing him pains, making his face even more harsh-looking. While receiving injection treatments for the disease, he tortured people, yelled at platoon commanders and squad leaders who returned from duty, and gave the soldiers binta (slaps on the cheeks or punches in the ears).

At one time, I captured many residents in a village north of Ajuy and was in the middle of interrogating them. Suddenly a man suspected as a guerrilla attacked a Japanese soldier with his binangon (large iron knife). I instantly drew my sword to face him. A pistol was fired, however, and the man fell down. A medical sergeant nearby had instinctively shot and hit him in the leg. Captain Watanabe who was standing close by got so furious that he beheaded the man on the spot. The Captain then went on to threaten the villagers: ‘His family must be here!’ Fear-stricken people became pale and pointed to a young woman. The Captain then yelled, ‘For the sake of the future, kill her as a warning to others!’ A soldier beheaded the crying woman and the three children who were with her in a blink of an eye.

I thought it was too much to kill women and children and looked at our battalion commander expecting him to stop this kind of behavior. However, Colonel Tozuka just turned his face away as if he could not bear watching the atrocious scene. Neither did he say anything to the Captain. Later on, I learned that the villagers were offering flowers at the scene of the massacre in grief and sympathy for this family.

News of the fierceness of our punitive force must have reached the town of Ajuy, but the people there did not run away. Instead, they assembled at the beach and expressed allegiance. Many houses displayed Japanese made posters and flyers of the independence of the Philippines to express their loyalty to the Japanese Army. This wholesale allegiance made it more difficult for us to conduct investigations among the locals. Meanwhile, some townspeople brought along a beautiful Filipina who was held in custody for some time at the field headquarters but eventually disappeared. I inquired about this from Captain Watanabe’s assistant. Apparently, her father or elder brother had cruelly murdered a crewmember of a Japanese military aircraft that had made an emergency landing in the mountains near Dingle soon after the outbreak of the war. I also learned that the woman’s sister had also been executed. The people’s dread must have reached its extreme limits that they just wanted to save themselves. Some villages definitely resisted the Japanese Army, while others willingly pledged allegiance and gave out information on where the guerrillas were in hiding.

We soon came to recognize that this pledge of allegiance was really a mock surrender following the ‘Lie Low’ policy ordered by Lieutenant Colonel Leopoldo Relunia, the guerrilla Division Commander. He also threatened the people with execution if they gave out information on the guerrillas to the Japanese Army. On the other hand, Captain Watanabe became even more furious upon realizing the trickery of the phony allegiance.

After the operations at Ajuy, the unit advanced north towards Sara where the main base of the enemy was. As I led a platoon through hilly forests, I picked up a bamboo basket on the grassy bank of a river. I thought it was just a plain item that had been discarded by a civilian. To my surprise, it contained an organizational listing of the 61st Division of the guerrillas. The 30 to 40 sheets of paper contained the entire formation, from the headquarters to platoon levels, with the names of their commanders. It also included code names for Governor Confesor, Colonel Peralta, Lieutenant Colonel Relunia and other top officers. The information generally coincided with that already obtained by Captain Watanabe’s Intelligence Section. We knew that here were 1,000 officers and 15,000 NCOs and enlisted men in the guerrilla forces. The papers were apparently lost by some high ranking officer of the 6th Military District headquarters amidst the confusion of a sudden evacuation. I quickly divided the men to search area but there was no trace of whoever that had been. We were t a step behind a very important person (VIP).

Before long, our platoon entered Sara. The guerrillas, leaving only remains of a concrete school building with a burnt-out roof, had razed the town center to the ground. We rested there that night. The main group was to go on with the operations while my unit was to remain at the school and prepare the propaganda for the surrender of the guerrillas. From the start, Sara residents showed allegiance, putting up white flags at their doors and pasting propaganda flyers of the Japanese Army. However, they must have been obeying the guerrilla order for deceptive surrender.