3.1 Mopping-up of the Guerrilla Bases

#Lieut Col Ryoichi Tozuka arrives in Panay

Early in December 1942, the new battalion commander Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka arrived at his new post. He had served as a battalion commander in the war in China and as an Independent Garrison commander in Manchuria.

Just before this time, battalion commander Lieutenant Colonel Senô who was assigned to the Antique province garrison left Panay. He was demoted and attached to the Sakhalin Regiment headquarters north of Japan where it was severely cold. He had apparenlly earned disapproval from Manila headquarters due to his August 1942 report that said, “Peace and order in Panay is quite good.”

By then, the organization of the guerrilla forces had become clear to the Japanese officers of the Panay garrison through interrogations of captured guerrillas. Lieutenant Colonel Peralta formed and commanded the IV Philippine Corps, the cadre units of which were the 61st Division in Panay, the 72nd Division in Negros and the 83rd Division in Cebu. The Panay guerrilla force had become the core of guerrilla warfare in the entire Visayas and by mid-December, Peralta had earned the rank of colonel. The commander of 61st Division in Panay was Lieutenant Colonel Leopoldo Relunia, and the Chief of the Staff and concurrent Commander of the 63rd Infantry Regiment was Lieutenant Colonel Julian Chaves. Their Division headquarters was located about 20 kilometers west of the town Of Calinog, near Mt. Dila-Dila and Mt. Baloy, close to the center of the mountain range that runs from north to south of western Panay.

On December 18, 1942, the headquarters of General Douglas MacArthur officially approved the organization of the IV Philippine Corps. However, it became difficult for the guerrillas to function properly as military forces and carry out military operations due to the mopping-up operations (sôtô) and punitive expeditions (tôbatsu) of the reinforced Japanese Army. Moreover, there are dissensions among them on different islands. On February 13, 1943, MacArthur dissolved the IV Philippine Corps in favor of the prewar military organization. Hence, the guerrilla forces of Panay became the 6th Military District, headed by Colonel Macario Peralta.

In early January 1943, the second phase of the mopping-up operations (kantei sakusen) began. The target area around Mt. Dila-Dila and Mt. Baloy where the main position of the guerrillas. The intention was to carry out a surprise attack on the position and capture of Division Relunia as well as Lieutenant Colonel Chaves, the Chief of Staff and Cornmander of the 63rd Infantry Regiment.

Even though the main forces had tanks deployed in the area, the results were not great. The troops only captured a guerrilla NCO and the mother of Lieutenant Colonel Chavez. Since the latter was an elderly woman, a carriage drawn by a carabao (water buffalo), i.e., carroza, was used to take her to Calinog. Later, she was placed under the charge of Governor Caram, discouraged, the 2nd company of the Kinoshita unit of the 171st IIB was left at the Calinog garrison while the trucks headed back to Iloilo City.

As the column of trucks moved toward the town of Lambunao, there was a huge explosion at the end of the line about two kilometers north of Januiay. As the troops gathered around, they saw that half of the road had turned into a hole that was three to four meters deep. They realized that a whole truck had exploded and more 10 soldiers on board had been blown into unrecognizable remains. The mopping-up operations ended with this major catastrophe and fear cased by a guerrilla landmine.

At this time, I was on garrison duty at Janiuay, I was accountable for the Suage River Bridge about 300 meters away from the garrison at the town center. On the adjacent plateau was a mango grove that was a favorite guerrilla ambush point. Due to the Japanese mopping-up operations, the guerrillas had scattered and avoided full-scale confrontations. However, villages and hamlets that were far from the main road remain under guerrilla control. They attempted attacks whenever they notice weaknesses in the Japanese defenses. When we took over the Janiuay garrison, there was a guerrilla fighting force north of the Suage River. Since the main Japanese troops were in combat near Mt. Dila-Dila and Mt. Baloy. I presumed that the routed enemies must have gathered this area.

Once I was scouting with a dozen soldiers. Around a kilometer north of the river, we came upon a wide basin, about 400 meters wide both east-to-west ans north-to-south. At the center is a road surrounded by forest, I sensed danger in this setting. Lance Corporal Taniyama and a few soldiers from the radio section were walking about 70 meters ahead. I was about to warn them when a young woman appeared by the banana grove in front of us. She was in our direction. Taniyama and the rest of this group happily waved back. When they were about 50 meters from her, she suddenly disappeared. Instantly, there was a volley of shots from the surrounding trees. Lead shots hit Taniyama directly and killed him on the spot.

We quickly withdrew to the high ground behind us and returned fire. Thus, the shooting went on for some time over Taniyama’s corpse. I estimated that there were around 50 to 60 of the enemy. There were only twelve of us and the enemy fire was increasing. So I dispatched a messenger to send a wireless call for reinforcements from the headquarters. The shooting continued into the evening when a relief force of 30-40 men arrived led by 1st Lieutenant Yoshioka and Sergeant Kurosawa and likely caused the guerrillas to withdraw. In the dark chilly night, we found Taniyama’s beheaded body that had been thrown into a ditch. We all searched for his head with our hands but finally had to return with only his headless corpse. As we stood around the remains of Lance Corporal Taniyama, we were seething with strong feelings for retaliation.

3.2 Ambush of the Army Commanding General Tanaka

Panay, after the second phase of mopping-up in mid-February 1943, appeared rather peaceful. This was mainly because of internal conflicts among local resistance forces and because they opted to avoid any confrontations with the main forces of the Japanese Army. People came back to Iloilo City, and the markets got crowded.

Manila headquarters sent Captain Junsuke Hiiomi and his propaganda unit of the Army Headquarters Department of Information (Hôdôbu) to Panay for propaganda work. The propaganda unit, with the Gunsei Kambu and the cooperation of the civil government of the Philippines, distributed posters and flyers. Garrison soldiers also went around towns and villages to ardently inform the people that, ‘We Japanese came to the Philippines to liberate you from American exploitation. The enemy of Japan is the US and Filipinos are our friends. We are the same brown color, pareho (the same) Orientals. Let us drive the Whites out of the East. We also guarantee the lives of the guerrillas who fall to the Japanese Army.’

There were reasonable results from these efforts. The Hitomi propaganda unit headquarters had plenty of stocks of soap, matches and other basic commodities, and distributed them to the villagers and townspeople. A civilian attached to the army named Kato–a university graduate in the US then employed by the Japanese Army–gave fluent speeches in English.

The Manila headquarters also dispatched a Strategy Section led by a captain who was a graduate from the Nakano school on intelligence. The leader never wore military uniform; he disguised himself as a civilian while collecting infomation and trying to make guerrillas fall into hands of the Japanese Army.

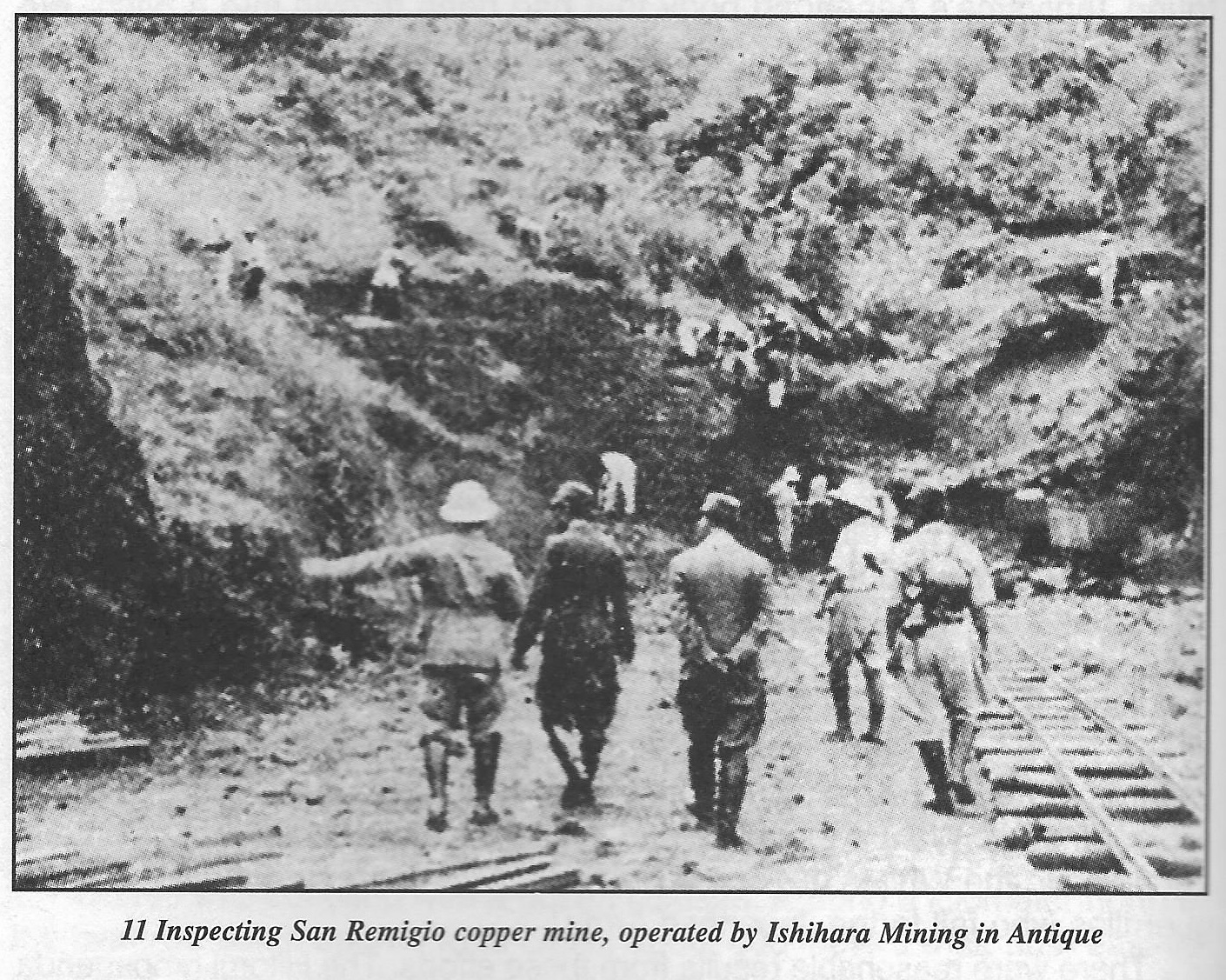

The business section of Iloilo City regained vigor with activities, such as the repair of steam engines and railways. The Shimamoto Ship Building Company built wooden ships, the Ishihara Company developed the copper mines at San Remigio, Antique and Pilar, Capiz, and Matsui Trading Company bought copra and sent sugar to Japan. Given this situation, the garrison headquarters at Cebu City must have rather extravagantly reported to Manila that this resurgence came because of the mopping up operations and subsequent peace in Iloilo.

|

|

#Ambush of Lt. Gen. Shizuichi Tanaka

Meanwhile, in Manila, the 14th Army Commanding General Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma had been relieved and sent back to Japan, blamed for the failure in the siege of the Bataan Peninsula. Lieutenant General Shizuichi Tanaka became the new Commanding General of the 14th Army. Soon after he took over the position, General Tanaka went around the main areas of the Philippines. When notified of his impending visit, the Panay garrison headquarters pulled together high-quality cars for his use and that of his delegation that included newspaper reporters. The Cebu garrison commander General Inoue personally came over to show General Tanaka around.

To the accompanying staff officers of General Tanaka from the Manila headquarters: General Inoue had recommended that the general should not pass Janiuay because of expected dangers beyond that area. If he should, I ask that General Tanaka be in an armored car. General Inoue was not very confident about the local security to show him around in a well appointed though unarmored car. However, those staff officers – who had only been familiar with the more peaceful situation in Manila and Luzon Island and who had never experienced the terrors of guerrilla warfare–said, ‘Well, it should be all right. The General is elderly, so let us take the cars.’

In the morning of February 20, 1943, aboard more than 10 cars, Commander Tanaka and other officers arrived at Janiuay where I was stationed as garrison commander. I assembled the neatly dressed soldiers and we nervously lined up on the road to welcome the general. The convoy was an unprecedented line of high-quality cars, the largest and most distinguished of which was the Commander’s vehicle. He was a solemn man with a prominent moustache, and he kindly thanked me for being dutiful. I looked at the line of cars and thought that this was dangerous.

Just three weeks before, I had been ambushed myself by guerrillas and the garrison had been attacked a few times. Though I warned unit commander Colonel Tozuka and Captain Watanabe of the dangers of guerrilla attack, they all left in the cars for Calinog as planned. Eventually, we heard the sounds of fierce firing from between the towns of Janiuay and Lambunao. I had about a dozen men with the party and that put us in a dangerous position. The firing lasted for about 15 minutes, after which we heard the sound of cars coming back. As the Commander’s car was making a sharp turn on a steep hill, waiting guerrillas started shooting from the left flanks. Several shots hit the General’s car and the kempei who guarded him was shot through the left eye. The General returned to Janiuay with his famous moustache drooping. He ordered for the packed lunch that they had brought with them. After a short rest, he left for further inspection – this time, in an armored car.

Upon the return of the officials to Iloilo City, garrison commander Inoue and the staff officers argued over the attack on General Tanaka. General Inoue shouted at the staff officers: ‘You are to blame for not listening to me and insisting on the inspection by the General in unarmored cars.’ Soon after, garrison commander Inoue got a relief order and returned to Japan. Major General Takeshi Kono took over his command. No reason was given for sending General Inoue away, but it appears that he had angered the 14th Army staff of Manila headquarters. From then on, the army staff decided on a policy meant to annihilate the Panay guerrillas.

On March 10, 1943, I was ordered to be Ordnance Officer (in charge of weapons) at the garrison headquarters then at the Iloilo High School.

In the last few months, Iloilo City had regained its prewar population. I was able to enjoy fresh vegetables and fruits, Chinese restaurant dishes, and became popular among young Filipinas at restaurants.

One day in April, Governor Fermin Caram invited me, along with Battalion Commander Tozuka, to dinner at his residence. The mother of Lieutenant Colonel Julian Chaves also attended and thanked the Commander that she was placed under the kind protection of the Governor.

3.3 Hamletting

Around April of 1943, following the suggestion of Captain Kengo Watanabe, the strategic villages system (i.e., hamletting or zonification) was introduced into the plains of Iloilo. This had been the practice by the Japanese Army in Manchuria, also later used by the US Army in the Vietnam War.

Certificates known as the cedula were issued to civilians in villages under Japanese Army control to distinguish them from villagers under guerrilla control. Mindful of the power balance between the guerrilla and the Japanese Army, some locals moved to what seemed to be safer areas. Of course, that was only a superficial allegiance and most of these villagers offered information to help guerrillas; some even led guerrillas into the strategic villages.

It might have appeared that the strategic villages were under Japanese control, but in reality, the guerrillas controlled most of them. People simply stayed in those villages because it was safe with the Japanese soldiers’ presence at night. We asked them to let us know as soon as a guerrilla entered the village, but no such news ever came in. The guerrillas and residents of the strategic villages were relatives and friends; they all held grudges against the Japanese Army that had brought on all the chaos in their lives since the invasion.

In consideration of the other villagers, guerrillas who entered the strategic villages did not attack nor commit acts of terrorism. However, they threatened Japanese soldiers in different ways. In one instance, a Japanese soldier went to a small beverage stand in Pavia where his favorite lovely girl sold tuba (an intoxicating drink from coconut sap). When he returned to the garrison, he suffered an awful pain and died. When his companions went to investigate, the stall and the girl were gone.

Guerrillas also used land mines and dynamite to blow up the trucks and cars of the Japanese Army. The tread of a tank of the Maeda platoon was blown off. Guerrillas sent in arsonists as well into the city. Even women and children were involved in setting off explosives and starting fires. The fires that broke out at night appeared to be signals for guerrillas to attack Japanese facilities, including the headquarters. They did these attacks to remind everyone of their existence. However, they also made city residents anxious, causing many to evacuate elsewhere. Tasked to bring back peace and order, the Kempeitai sought out the arsonists and dispatched scouts every night to prevent these guerrilla activities. Captain Watanabe also dispatched a nightly squad of scouts.

The guerrillas, however, were well aware of their activities. They attacked and killed the scouts one after another. Therefore, Watanabe decided to use Filipino spies to collect information. Among them were a few former thieves and criminals as well as some POWs who cooperated for fear of their lives. At first, as soon as they brought information, soldiers and kempeis went out disguised as locals and arrested some guerrillas. However, local citizens despised those spies who worked for the Japanese and this made it difficult for the Japanese to get useful information. Moreover, some of the spies took advantage of Japanese support by robbing decent citizens of money and other articles. Occasionally, taking liberties during an official search, they stole and even raped women, thus eroding the people’s trust in the Japanese Army.

Naturally, the guerrillas brutally punished the spies who worked for the Japanese, killing quite a number of them. Some went missing. Others had to work for the guerrillas by counter-spying on the Japanese. The ‘Spy Game’ was in total confusion, but there were indeed some spies whose work for the Japanese Army produced some results.

Whatever information he got, Captain Watanabe reacted at night, arresting suspects and detaining them in the locked cell at the basement of the Iloilo High School headquarters. There were always about 30-40 suspects cramped inside the jail cell and the accompanying investigation was extremely cruel. Suspects were beaten with bats, forcibly filled with water until their stomachs swelled, causing them to yell and shout all day. When they gave out information, Captain Watanabe forced them to show the way on nighttime searching trips. The suspects knew this and so endured the torture as long as they could. The ones released were those who revealed the correct information that led to the capture of new guerrillas. Then, the guerrillas captured and executed them in retaliation. Some who served the guerrillas did so to avoid their sanctions, or else, to exact revenge. Thus, they led guerrilla attacks on the garrison or other facilities of the Japanese Army.

The prison was so full that there was no space to lie down. Since it was impossible to detain many guerrillas or to spare enough guards, Captain Watanabe had to release the guerrillas and suspects he had arrested. However, once released, they not only gave information to the guerrillas but also led the attacks of the guerrillas on the garrison. Eventually, therefore, the Intelligence Section started to execute the guerrilla suspects.

Japanese soldiers who had witnessed the terrible deaths of their close friends slain by the guerrillas became anxious and terrified, fearing a similar fate. They changed their opinions and resolved that they should kill guerrillas before they got themselves killed.

Among the Japanese soldiers was a former Buddhist monk around 30 years of age, who always recited Buddhist sutra (prayers) after each execution. But when his comrades were killed one after another, even he started saying, ‘Unless we kill them, we will be killed,’ and became indifferent of the execution of the guerrillas.

The retaliation of the guerrillas also got more and more brutal. In the hatred generated by these circumstances, the guerrillas and the Japanese as well had forgotten the noble causes of ‘Defense of My Country’, ‘Holy War’, and ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’. Each side tried to kill as many enemies as possible, and Panay became an island of murder and slaughter. On both sides, there were extreme unnatural behaviors that were beyond common sense.

During the propaganda and pacification campaigns, the captured guerrillas as POWs were all released after a short period of imprisonment with propaganda leaflets and other goods. Some guerrillas made themselves easy captives knowing that they would soon be set free, making use of the situation to obtain more information on the Japanese Army. Some released POWs became guerrillas once again because they could not get a job or food in areas controlled by the Japanese Army. As a condition for taking them back, they were forced to supply the guerrillas with some information on the Japanese or lead attacks on Japanese facilities or barracks. Surprise attacks often led to many Japanese casualties.

Within the Japanese Army, some called for measures that were more stringent. There were observations of some local residents that Japanese ways were more lenient than American suppression of guerrillas at the turn of the century when the US Army occupied the Philippines. These advocates argued that our ways then would not be able to subdue the Panay guerrillas who were the most dauntless of all in the Philippines. Captain Watanabe eagerly studied the US Army annihilation strategies in the Philippine-American War in 1899, and the results were evident in the later subjugation of the guerrillas.