(The start of Captain Toshimi Kumai’s experiences in Panay)

2.1 Withdrawal of the Japanese Army Garrisons

In August 1942, after the capture of the Bataan Peninsula and the mopping-up operations in northern Luzon, I was a Second Lieutenant serving as garrison commander at the town of Urdaneta, Pangasinan in northern Luzon. I was enjoying myself there since the wartime atmosphere was not felt in that area. Towards the end of September, I was transferred to south San Fernando, Pampanga, 50 kilometers north of Manila. There I joined the newly organized 11th Independent Garrison that was to be assigned to the Visayas under the command of Major General Yasushi Inoue. I became the machine-gun platoon leader of the 3rd Company (commanded by 1st Lieutenant Teruo Kawano) of the 37th IIB led by Major Hisashi Fukutome. I was glad to find that among my subordinates were squad leaders Sergeant Okazaki and Corporal Matsuo who were already squad leaders when we engaged in the capture of Bataan Peninsula. Only then did we learn that there was fierce guerrilla resistance in the Visayas. Then, the orders arrived. The Fukutome battalion was assigned to join the Panay garrison. The 2nd Company’s Nagano unit was sent to the Bohol garrison, and the 36th Battalion’s Ômori unit was sent to the Leyte garrison.

On October 9, 1942, we boarded the transport ship, Kiso Maru (about 8,000 tons), which then left Manila and arrived at the shores of Iloilo City in the afternoon on October 12. From the ship, the city looked beautiful and seemed like a romantic southern paradise. However, our ship arrived at the seawall that was devoid of people. It was an eerie sight. We entered the city on trucks. On the way, we passed the road in front of the Spanish fortress, Fort San Pedro, which had become a prisoner of war (POW) camp. We saw 200 to 300 POWs staring at us devoid of expressions.

As soon as we entered Iloilo City, however, I was surprised to see the burnt ruins of a dead city. That there were only a few nervous people gave me a feeling of great fear and anxiety. I thought that I could not return to Japan alive.

By the next day, the 37th IIB under Major Fukutome took over garrison duties from our predecessors, the 33th IIB under Lieutenant Colonel Senô.

One day after taking over new duties with the 3rd company, we went out to Oton, 20 kilometers west from Iloilo City, under the guidance of members of the Keimpeitai. We were to learn how to subjugate the guerrillas. The empty houses and huts along the road made us fearful of the safety of our trip. Near the Oton churchyard, we first witnessed the interrogation and torture of two guerrilla suspects. The military police (kempei) poured water from a pail into the suspect’s mouth, causing him much pain as his stomach swelled up in seconds. Soldiers of our unit called out for the kempei to stop. Company Commander Kawano and I also admonished him to stop the torture at once. The next day, Captain Kengo Watanabe, the Operations and Intelligence chief, scolded Kawano for his interference in the information gathering process.

On October 15, the 3rd Company of the Fukutome unit and the 3rd Company of the Senô unit were ordered to take over the alternate garrison at Pototan, 34 kilometers northeast of Iloilo City. For the first time in Panay, enemy forces confronted us just outside of Iloilo City. They frontally attacked us from coconut groves as well as on our right flank. I crossed a deep river and positioned the heavy machinegun on the roadside. For forty minutes, we exchanged fire. Eventually, the enemy withdrew, although the Kawano Company of the Fukutome unit remained at the nearby bridge. Meanwhile, the Takahashi Company of the Senô unit completed the takeover of the garrison at the Pototan plaza.

The next morning, the new garrison at Pototan guarded by the Tanabe Platoon of the 1st Company of the Fukutome unit was under guerrilla attack. There were only around 50 inexperienced soldiers who were unfamiliar with guerrilla warfare. Running low on ammunition, they radioed for relief from garrison headquarters at Iloilo City.

Two days later, several trucks loaded with around 50 soldiers, ammunition and food left for the relief of the Pototan garrison. However, one of them soon returned to the city with the wounded commander of the relief force. He reported their ambush by guerrillas at a bridge before the town plaza of Zarraga, south of Pototan. The incident caused the ——- of some trucks and soldiers as well as the death of the machine gunner, among the four or five killed.

The unit commander, Major Fukutome, ordered me as leader of around 25 soldiers, including Second Lieutenant Toyota of the 3rd Company to replace the relief group. We rushed out with a captured US field gun. At the bridge, there were around 20 fear-stricken soldiers. I positioned the field gun on the road amidst a shower of bullets from the enemy. I fired about ten times directly into the wooded area where the guerrillas hid. Then, I let out a few more shots to the top of the trees where there were likely to have been snipers, and further on towards Zarraga. The light machine-guns of the Satô platoon were also firing. We saw enemies but there were sporadic shots from their direction. For two hours, we faced them head-on. Towards dusk, we dashed as a group, letting out battles cries through the forest and into the town plaza. The drivers and soldiers of three or four of our trucks parked by the roadside held on to their weapons and maintained a defensive circle. They were overjoyed with tears to see the relief force. That night we surrounded the trucks full of ammunition and kept watch, fearful of a guerrilla attack.

At dawn of the next day, Battalion Commander Fukutome and Captain Kengo Watanabe accompanied the reinforcements from the Yoshioka 4th Company that joined us. During the night, they decided to withdraw the Japanese forces from the Pototan garrison and came to assist us. I was on the first truck as we moved towards Pototan. For 13 kilometers on the road, we could not see anyone. Yet the tense atmosphere signified the presence of hidden guerrillas. As a precaution, we got off the vehicles every time we were near wooded areas and looked carefully in all directions.

Five or six kilometers east of Pototan. the guerrilla attack began. The Japanese soldiers scattered along the road and slowly advanced. As we neared a forested area, every shot from the guerrillas killed a Japanese soldier. Hence, the others could not move on and only lay flat on the road. The airplane we had summoned flew over where we were; but the crew could not attack the hidden enemy in the jungle. Our soldiers, however, were shot successively as they stood up to wave to the plane.

Evening fell and the need for relief of the Pototan garrison was urgent. We set two heavy machine-guns on the left side of the road and, shooting blindly, we were able to advance a bit. Soon, however, there was a return of fire, and a soldier next to me was killed. It grew darker in the forest and we could not see an inch ahead. Major Fukutom madly repeated. ‘It is impossible to go further.’ He gave up the relief effort when we were just about a kilometer and a half from the Pototan garrison. The commander’s abandonment of the soldiers to their fate made us feel even more insecure.

At the Pototan garrison were Corporal Yokoo and other members of my Old squad in the battles of Bataan. I volunteered to pursue the relief effort and set off with four or five soldiers. To avoid an ambush by the guerrillas, we approached through rice fields but our advance was difficult since the field was heavy with mud. As we struggled forward, we observed beam of a flashlight making circles in the grove ahead of us. Realizing that it came from the garrison, we made a furious dash toward the light.

Second Lieutenant Tanabe and Corporal Yokoo, who had set up their position around four or five village houses, wept happily when they met us. Immediately, we took as much weaponry and ammunition as possible and withdrew. Since it would take too much time to go through the rice fields again, we rushed through the main road, mindful of the dangers of doing so. As we reached the area where we had left the main force, we discovered that the unit Commander, Major Fukutome, and others had already retreated to Iloilo City. We jumped into the waiting truck and drove at full speed back to the city through night.

This was the first confrontation with guerrillas by the main forces of the 37th Independent Infantry Battalion. We experienced defeat and great loss by retreating from the Pototan garrison only five days after its takeover. My subordinates and I were angry at having been abandoned by the unit commander’s hasty retreat. (Second Lieutenant Tanabe, who was thankful to me for having saved his life, was killed later in the war.)

Our withdrawal from the Pototan garrison re-energized the guerrillas who started to assail the garrison headquarters at the Iloilo Provincial Capitol in the city. Their attacks on the airfield at Mandurriao and the garrisons in La Paz, Jaro, and Molo also became more severe. Because of these incidents, the shops in the city closed early and the streets were empty at night. At one time, the guerrillas even harassed the residence of Major Fukutome, although the guards were able to beat them off. Nonetheless, fear had worsened the commander’s nervous breakdown. He became more irritable and often yelled at others. Thus, he did not get along well with Captain Kengo Watanabe, a senior officer who was the chief of the Operations and Intelligence Section. The operations room did not work well and the headquarters did not function, as it should have.

2.2 Seige of the Santa Barbara Garrison

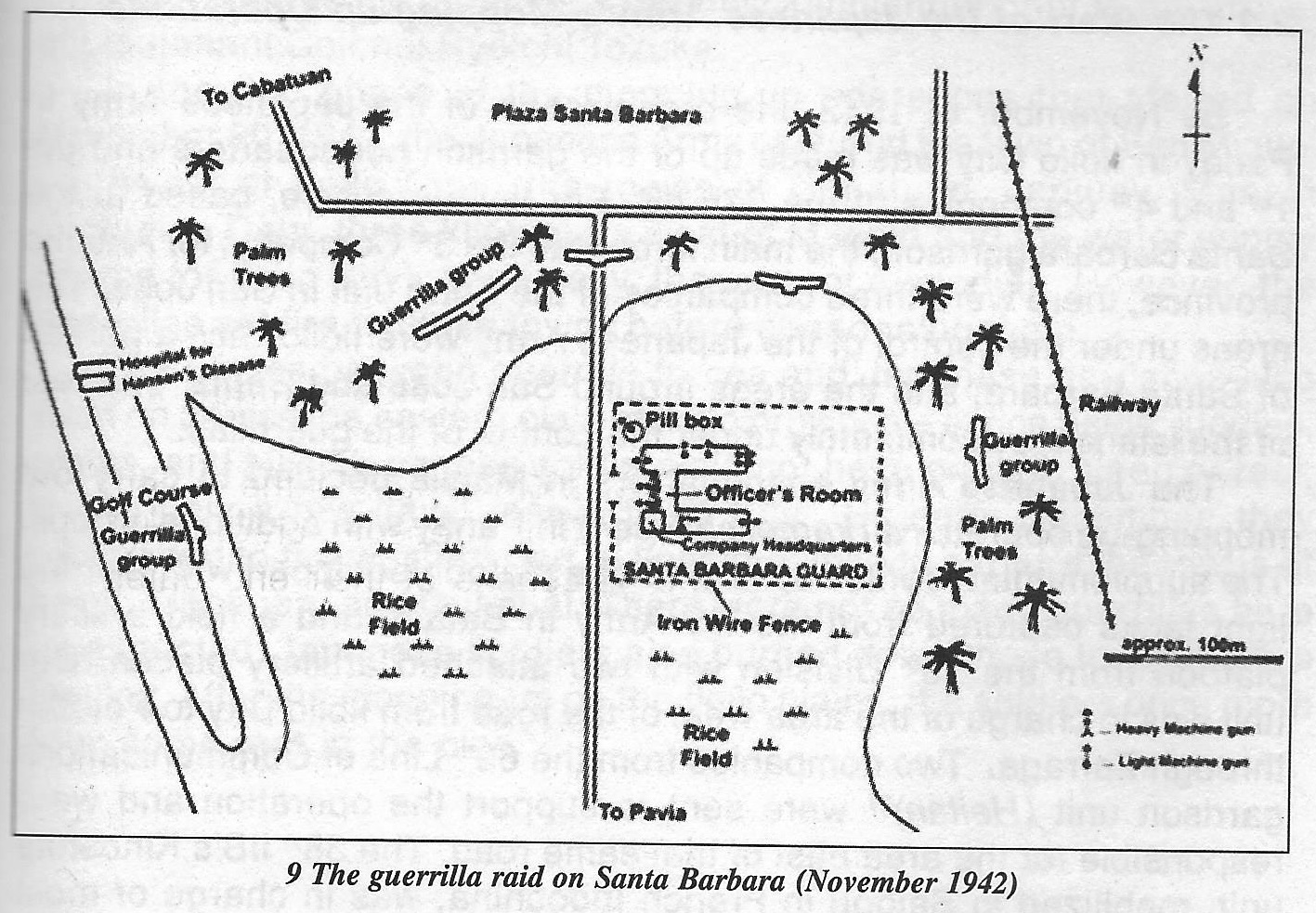

The Pototan withdrawal heightened the troops’ fears of the guerrillas and caused the deterioration of the unit’s morale. The next assignment of the Kawano unit of the 3rd Company, to which I belonged, was to replace the occupying forces at the Santa Barbara garrison. We did that in late October without any guerrilla attack. The garrison was at a former elementary school in Santa Barbara, 20 kilometers north of lloilo City. The Concrete school building was along the main road. There was an athletic field on the east, rice fields to the south, a coconut grove 60 meters to the north and northwest, and a plateau on the west where a golf curse and a leprosarium were located. It was the last remaining Japanese garrison of the Seno unit outside of lloilo City and, inevitably, a primary target for the guerrillas.

Before dawn, one day early in November, two heavy machine guns set at the garrison’s main gate suddenly started to fire. We heard voices of the enemy on the road between the shooting and we jumped to our position in our underwear. The attack lasted for days. In the tropical climate, corpses deteriorated after half a day. Therefore, we cremated the bodies at the school grounds at night under enemy fire. The enemy was thus aware of the casualties we sustained. We sent daily reports of the results to the battalion headquarters and they reluctantly decided to send reinforcements to the garrison. A detachment led by the unit commander himself left Iloilo for the relief of Santa Barbara. This was made up of 250 soldiers from the headquarters–the 1st Company and a platoon led by Second Lieutenant Toyota of the 3rd Company.

However, guerrillas ambushed the relief force between Pavia and Santa Barbara, killing nine mud-covered soldiers, including the veteran Sergeant Gunji. Despite serious damage, the relief force managed to reach the Garrison. On seeing the unit commander in mud-covered boots, the armed guard at the main gate hurriedly saluted him. Major Fukutome shouted. ‘How dare you! It is dangerous for me when you salute like that. It tells the enemy that I am the commander!’ Anxious and broken down with fear and fatigue, he collapsed into the chair at the company commander’s office. He was in no condition to either listen to our report or be appreciative of our service. Seeing the commander of the Panay garrison in such shape made me feel desperate aboul the future.

Soon after, NCOs (kashikan) and soldiers (heishi) of the 1st Company hastily staggered into the garrison shouting. ‘Creosote, creosote!” Mud was all over them. Evidence of the fierceness of their encounter. The company had attacked the guerrillas on the plateau west of the main road and pushed on until they reached the leprosarium. At the hospital, the combat-weary and thirsty soldiers quickly drank from water containers. The Filipino patients tried to stop them. calling out, ‘Leper, leper!’ However, the soldiers only realized the significance of their warning after they had drank water from those containers. That was why they wanted creosote to wash out what they had just taken in.

Later on. Major Fukutome told them, ‘Since there is not enough manpower, I will not he able to come so often to reinforce your defense. You yourselves should take courage and perform your duty. He then distributed Shinto medallion charms to each of the officers. We were disheartened on receiving the amulets, aware that this was headquarters’ response to the guerrilla attacks.

The worst experience of the reinforcement operations fell on Second Lieutenant Toyota and his detachment of more than 30 men. Guerrillas ambushed them near Barrio Buyo in Santa Barbara along the Aganan River. Outnumbered, Private First Class Namba was killed and 12 others were injured as they battled for a day and a half. Since they were running out of bullets, they hurriedly cut an arm off Namba’s corpse and buried his body as they managed to withdraw. Some days afterward, under the watch of the Jaro garrison, the guerrillas dug out the corpse of Private First Class Namba and suspended it on a leg of a bridge over the Jaro River. We felt outraged at this insult to the dead since it demonstrated how strongly the guerrillas hated the Japanese Army. It made us feel the cruelty of the war, yet we also got ready to retaliate on the guerrillas we would come across.

9. The guerrilla raid on Santa Barbara (November 1942) |

From experience, we knew that it was disadvantageous and dangerous for us to remain confined in the hot galvanized iron sheet-roofed building. As a result, scout patrols of a squad, and eventually a platoon, were dispatched into the surrounding coconut groves and the main streets of Barbara. A shot on the chest killed my–subordinate, Sergeant Okazaki, the bravest member if the company along with Private First Class Komamura. Most houses were burned down and the local residents had run away.

The attacks by the guerrillas became less frequent; but when they did so from time to time, they attacked fiercely. The unit commander’s nervous breakdown kept getting worse and he would yell at everybody. Major Fukutome made himself an object of laughter since he had soldiers guard his accommodations. Eventually, fed up with the situation, Captain Watanabe requested the Visayas garrison headquarters at Cebu that a psychiatrist should examine the commander. As a result, the unit commander left Japan for tnree months after his assignment to the 37th IIB. Thereafter, he became an officer attached to the Rikugun Yonen Gakko (Military Youth Academy). In the absence of the commander, Captain Watanabe served as the battalion’s Deputy Commander.

2.3 The Start of the Japanese Army’s Mopping-up Operations

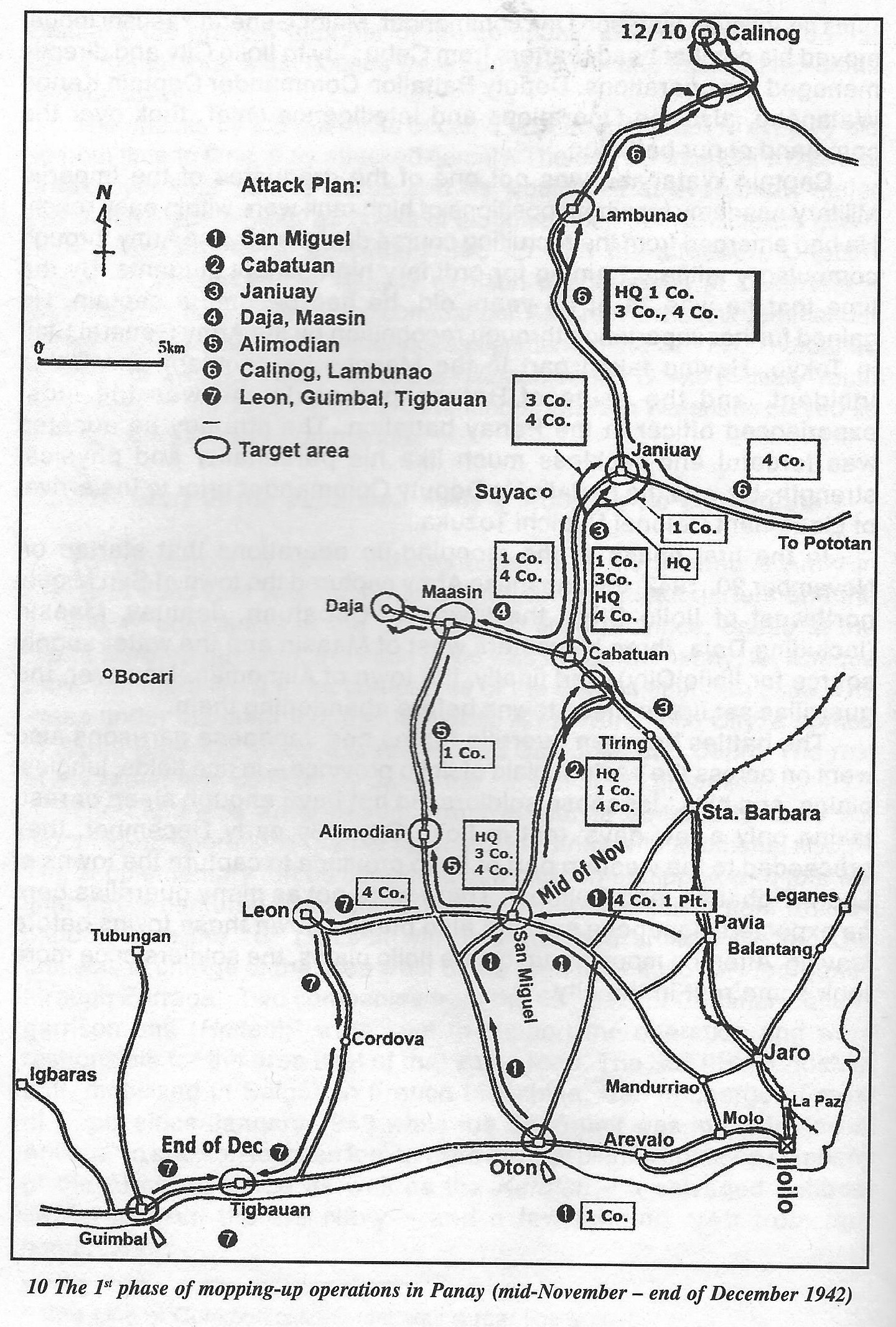

By November of 1942, the organization of the Japanese Army in Panay in lloilo City was made up of the garrison headquarters and the 1st’ and 4th companies of the 37th IIB. For Iloilo province, based at the Santa Barbara garrison, the rnain force was the 3rd Company; for Antique province. there were three companies of the Senô unit in San Jose. The areas under the control of the Japanese Army were Iloilo City, a portion ot Santa Barbara, and the areas around San Jose and Capiz.

The Japanese Army headquarters in Manila decided to carry out mopping-up operations (kantei sakusen) in Panay with additional troops. The supplementary forces consisted of a platoon equipped with four M3 light tanks captured from the US Army in Bataan and a field artillery platoon from the 16th Division with two attached artillery pieces. Our unit was in charge of !he area west of the road from Iloilo City to Pototan through Zarraga. Two companies from the 63rd Line of Communications garrison unit (Heitan)’ were sent to support !he operation and were responsible for the area eust of that same road. The 38th IlB’s Kinoshita unit, mobilized in Saigon in French Indochina, was in charge of most of Capiz since January 1943 while the Senô unit was in command of Antique. In addition to these forces were several planes from one company of Ihe Army Air Force as well as the Karatsu —. a salvaged gunboat captured from the US Navy–and a few landing craft from port headquarters.

The Visayas Garrison Unit commander, Major General Yasushi Inoue, moved his combat headquarters from Cebu City to Iloilo City and directly managed the operations. Deputy Battalion Commander Captain Kengo Watanabe, also the Operations and Intelligence chief took over the command of our battalion.

Captain Watanabe was not one of the graduates of the Imperial Military Academy for whom positions of high rank were within easy reach. He had emerged from the recruiting course designed by the Army through compulsory military training for ordinary high school students. By the time that he was 34 or 35 years old, he had become a captain. He gained further importance through recognition by the Army General Staff in Tokyo. Having taken part in the Manchurian incident, the China Incident and the siege of Bataan peninsula, he was the most experienced officer in the Panay battalion. The strategy he adopted was forceful and reckless much like his personality and physical strength. He was the battalion’s Deputy Commander prior to the arrival of Lieutenant Colonel Ryoichi Tozuka.

In the first phase ol the mopping-up operations that started on November 20, 1942, the Japanese Army captured the town of San Miguel northwest of lloilo City, the towns of Cabatuan, Janiuay, Maasin (including Daja, three kilometers west of Maasin and the water supply source for Iloilo City), and finally, the town of Alimodian. However, the guerrillas set fire to these towns before abandoning them.

The battles between guerrilla forces and Japanese garrisons also went on across the eastern plain of Iloilo province–in rice fields. jungles, plains, and hills. Japanese soldiers did not have enough sleep or rest, taking only a few days’ rest in Iloilo City. By early December, they proceeded to the western part of Iloilo province to capture the towns of Leon, Tigbauan, and Guimbal. There were not as many guerrillas here as expected. Japanese soldiers also burned down these towns before leaving. After the mopping-up on the Iloilo plains, the soldiers once more took some rest in the city.

|