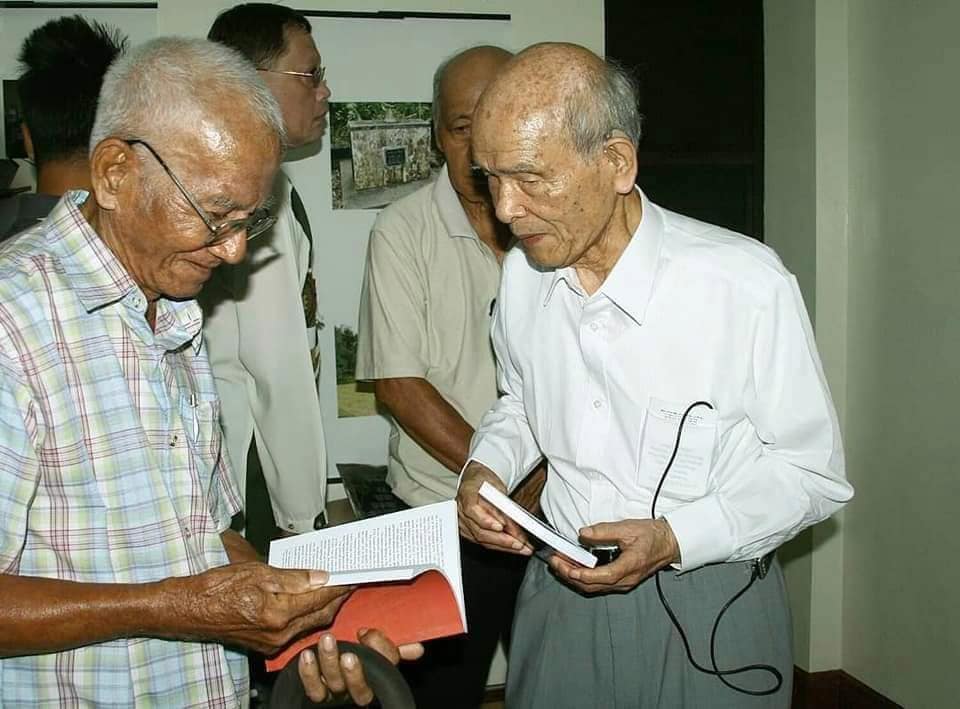

Patricio Confesor Jr. (left), son of Patricio Confesor (wartime Deputy Governor of Panay and Romblon) and nephew of Tomas confesor, with Toshimi Kumai  Patricio Confesor Jr. (left), son of Patricio Confesor (wartime Deputy Governor of Panay and Romblon) and nephew of Tomas confesor, with Toshimi Kumai Photo courtesy of Tara Yap |

by Yukako Ibuki

In Panay Island, which is sixth largest of all the islands of the Philippines, and situated in West Visayas, March 18 is celebrated as “Victory Day”, commemorating the landing of US Forces during the Pacific War. 64 years after the war, from March 25 to 30, former Captain Toshimi Kumai, adjutant of the Japanese Army Panay Garrison, paid his sixth visit to Panay, the first being in October 1942. At the “Pacific War Exhibition,” which is being held at the largest shopping mall of Iloilo city, 91 year-old Mr. Kumai is seen explaining the photos to the visiting citizens. Ms Chizuko Sakamoto, who used to be a student in Manila, is at the back of his wheelchair. For the special events featuring Mr. Kumai, she had flown from Seoul, where she continues her doctorate studies at Yonsei University on the issue of the comfort women. In the other photograph, author Kumai is shown autographing his book.

“On February 20, 1943, the Japanese Army Commander insisted on carrying out his visit in high quality cars ignoring the warnings given by the Panay Garrison. This resulted in a big incident, where the convoy was fired at by ambushing guerrillas, and the Army Commander managed to escape on all fours. In order to erase off the humiliation, Army Headquarters ordered a Great Punitive Campaign of a retaliatory nature, for half a year from July to December of 1943. Around 10,000 local people are said to have been sacrificed, being victimized in the campaign.”

“In March, 1945, upon the landing of US Forces on Panay, we were ordered to abandon Iloilo City and advance into the mountains. Bocari, which we had come to know during the Punitive Campaign of July 1943, was appropriate for a position from the viewpoints of geography and food. Situated in Bocari, our forces repeatedly repulsed the attacks of the US forces, continuously confronting them, and finally surrendered by the order of the Japanese Army, in the beginning of September with no deaths by starvation in our unit. However, during the forceful break-through to the mountains from Iloilo City, more than forty exhausted hojin, the Japanese residents before the war, committed mass suicide at midnight of March 21.” So explained Mr. Kumai.

Mr. Kumai, after the surrender, was tried and sentenced to twenty-five years of hard labor at the B&C class Manila War Crimes Tribunal, which he served in the Philippines and in Sugamo, and was released in February 1954. For some years, he tried to forget his fourteen years of war and war criminal experiences. However, he decided to come back to Panay due to his sense of responsibility as a surviving member of the Panay Garrison. In 1974, he and his colleagues made their first visit of Panay after the war, and tried to collect remains of their fallen comrades, and at the site of the hojin mass suicides, they learned that at least six children had been saved and brought up by the local people.

In 1977, he published his war experiences in a book, from Jiji-tsushin Press; the title in English means “Blood and Mud of the Philippines: the Worst Anti-Guerrilla Warfare in the Pacific War.” Since then he and his comrades, with hojins, invited the Japanese orphans to Japan and looked for their relatives, built a memorial for Hojin in the Soyac mountainside, and set up another in memory of the victims from the Philippines/US/Japan in Iloilo city, working for friendship with people of Panay.

As time passed by, the memorial in the mountain got damaged and began to decay, worrying Kumai that everything would eventually be forgotten. As he kept working with his wish of moving the memorial into the city area, it happened that in 2008 he met with Mr. Masataka Ajiro, Director of the Japan-Philippines Volunteer Association.

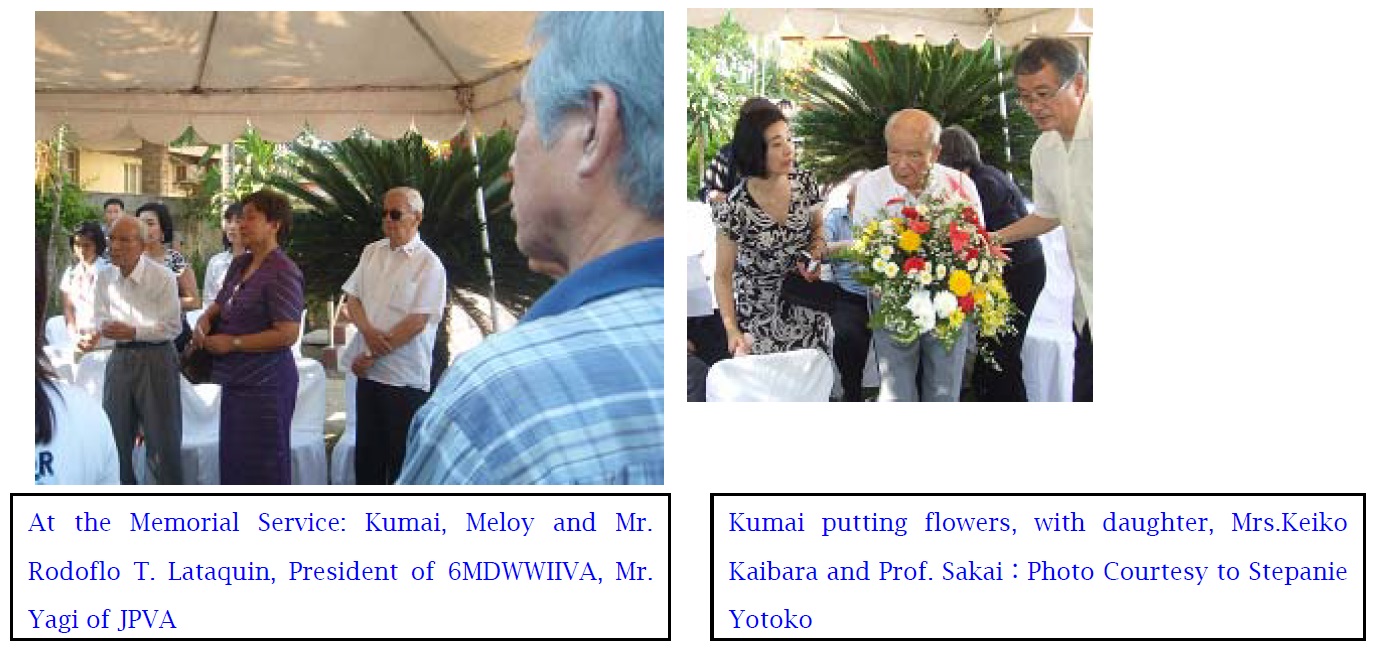

The Suyac Hojin Memorial was moved to the ground of the Nikkeijin-Kaikan, the Japanese Descendants Association Hall, in the city with the assistance of Mr. Ajiro and the Nikkeijin-kai, the Japanese Descendants Association. The joy of Mr. Kumai and his colleagues is great, whose long-held dream had been achieved. On March 28, a memorial service was held, Mr. Kumai having placed into the new memorial the remains of the victims found in recent years. Beside it, a war material museum was opened in the same site, named as the “Peace Memorial Museum,” holding the precious documents accumulated by Mr. Kumai. Professor Tomoji Sakai of Tokiwa University has made a plan of the Japanese and Filipino war materials museum, full of new ideas such as bilateral exhibitions by students of both countries, equipped with computer access. He and three of his students worked hard since March 24, and arranged the display for this occasion.

In 2003, I came across Mr. Kumai’s book at the library of Yasukuni Shrine, whose collection is the best regarding the Pacific War. I was impressed with its value as a record, and the responsible stance of the author as a survivor. Writing to him, with my sample translation, I was given permission to translate. Through Mr. Kumai’s introduction, Professor Ma Luisa (Meloy) Mabunay of UP Visayas, who is the expert on the Panay hojin, graciously agreed to edit, and she invited Professor Ricardo (Rico) T. Jose of UP Dilman to give notes to the incidents, from his profound knowledge of the Philippines under the Japanese occupation. With the support of Mr. Ajiro, and the notes completed up to Chapter III, 500 copies were printed for distribution at this occasion. The author and translator express our heartfelt appreciation to the gifted Professors Mabunay and Jose for their sincere work, amid a lot of responsibilities they have. We thank from the bottom of our heart for the understanding and kind assistance given by Mr Masataka Ajiro. The formal publication is expected on the completion of the notes by respected Professor Jose.

Mr. Kumai could accomplish his sixth visit to Panay, including his war days, having managed to get the doctor’s permission issued on March 11. However, Mr. Ajiro, who had promoted Mr. Kumai’s projects through monthly visits of Panay and Mindanao, developed some health problem and received a medical order to rest. The attendants remembered with gratitude both Mr. Ajiro and Professor Rico, who had some academic obligations to carry out in Tokyo.

March 28: Memorial Service and Opening Ceremony of the Peace Memorial Museum

Above photos courtesy of Tara Yap

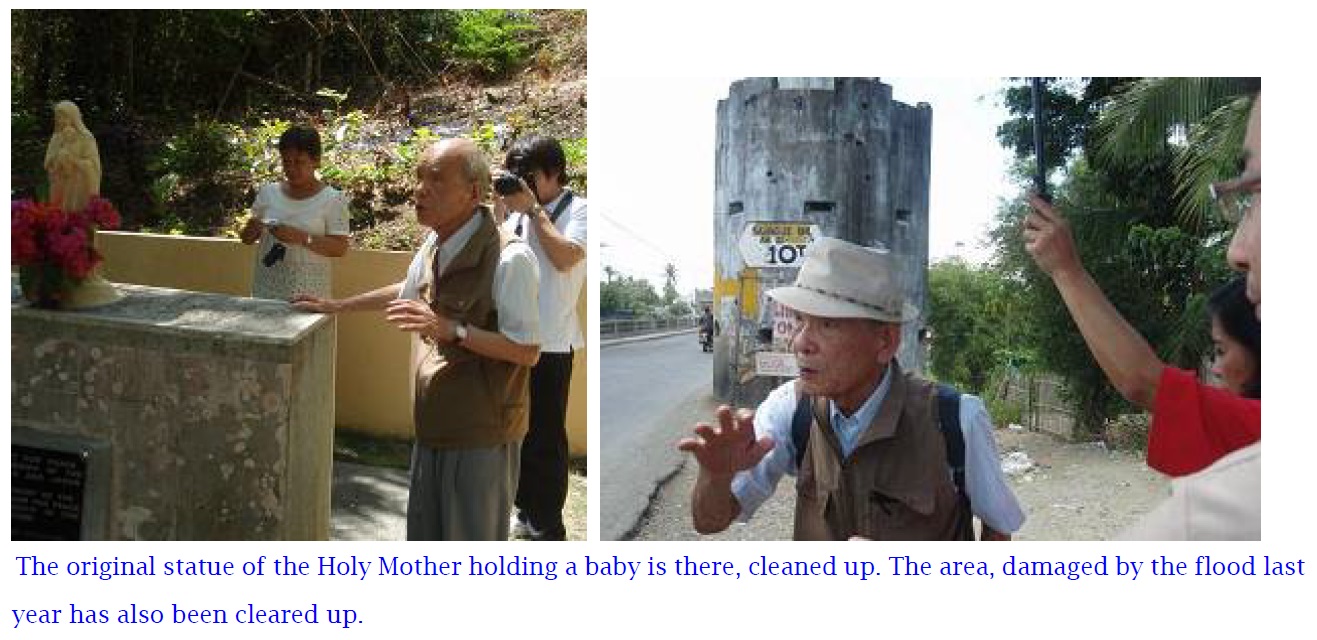

March 29: Visiting Old Memorable Sites, and People

Mr. Kumai and his group visited Soyac, in vehicles provided by UP Visayas through the kind arrangement by Professor Meloy. On the way, he explained a lot of sites familiar to him in his war memories. He looked touched to see the very buildings he knew that have survived all these years. The area where a group of hojin, led by Principal Kayamori of the Iloilo Japanese School, killed themselves, was away from the city, after the car had climbed up the narrow mountain path for some time. Everyone, including Kumai, had to get off and walk the last distance. After the remains and memorial plaque had been moved into the new memorial at site of the Nikkeijin-kaikan, the place was turned into a “Peace Park,” where a comfortable hut, with bench, was newly built in front of the old Memorial. After the original plaque was relocated, a new one by the Nikkeijin-kai was installed.

On the way from Iloilo City to the mountains, we crossed the bridge of Janiuay, where the Japanese tochika (pillbox) still stands. It was built for the protection of the important bridge on the big Molo River, but having been designed by an officer who was in the cold climate of Manchuria, the inside was as hot as a steam bath, so it functioned just as deterrent, he explained. Driving around the suburbs of Iloilo, listening to Kumai’s story, I couldn’t but feel shocked to think about the warfare that happened in this beautiful green country. Mr. Kumai writes that in his first revisit in 1974, the people of Panay were already kind and friendly to him and his group, who tried to look for the remains of the Japanese soldiers and civilians. They had even brought up some Japanese orphans.

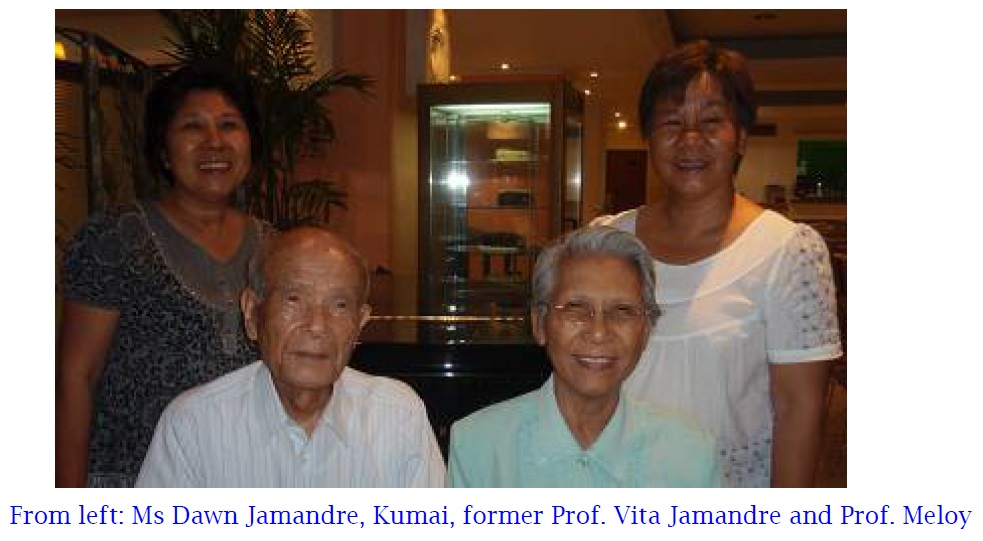

Through Professor Meloy’s introduction, Mr. Kumai met the Jamandres five years ago. Mrs. Vita Jamandre’s mother, the late Mrs. Natividad Mallari was tortured by the Japanese Kempeitai in Fort Santiago, as she had been helping her brother, who was a guerrilla. After the war, she regularly visited them (the Japanese Kempeitai) in Muntinglupa, where they were held as war criminals, a lot of them being sentenced to death. She supported them with her Christian faith and love, becoming a close friend of them. The late Mr. Gintaro Shirota, who I could meet twice and the author of the well-known “Song of Muntinglupa”, and many others invited her to Japan, and their friendship involving their families is still alive.

Mr. Kumai was rather close with Mrs. Mallari’s other brother, the late Major Sanlap of the Philippine Constabulary(PC), who he talked about Judo, and so on. Compared to former guerrillas, former PCs and others, who were regarded as Japanese collaborators had difficult years after the war. Former Professor Vita studied music in the US, including the Suzuki Method, and was teaching at Central Panay University(CPU). That evening, she played Japanese music on the piano, the “Song of the Seashore”(Hamabe no Uta) in her beautiful arrangement, which she had learned from former Captain Mikio Kai, Commander of San Joaquin Garrison.

March 30: Accompanying Chizuko Sakamoto’s Interviews

Miss Chizuko Sakamoto visited Soyac of Panay on her own in 2008, which she filmed herself. With editing by Mr. Kohji Nanba, a film maker, her trip was made into a neat documentary film. During the visit this time, she has been documenting another version of Mr. Kumai’s story, with Kohji at the video camera. Mr. Kumai, who arrived in Panay on March 25 and had cooperated in Chizuko’s film making, returned to Tokyo this day.

I was allowed to accompany the two young people, who wanted to film some Filipino survivors of the war. We went around the shopping mall, the Catholic mass at noon, looking for the elderly in their 70s or older, but everyone we saw were young. Dawn told us, “The elderly rest at home during the day when the heat is strong, no families let them go out.” She kindly met us for lunch, and then arranged an interview of a friend, and offered the role of chauffer to carry out Kohji’s wishes to film some bridges in the old battlefields.

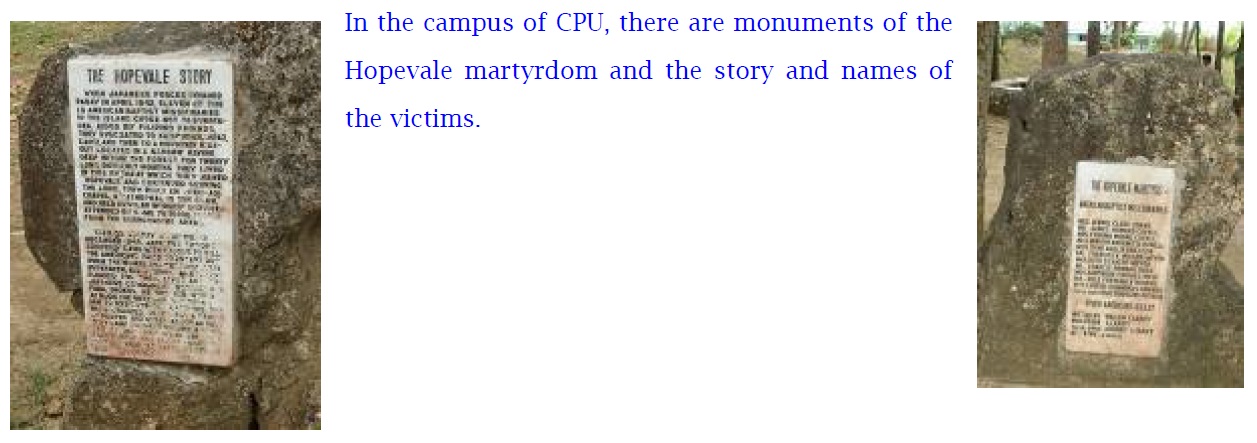

Ms Neonita Alasa Gobuyan is a well-known producer, who was two years old when the war ended. Her parents were Christians, who were among the supporters of more than eleven missionaries, who were captured and executed by the Japanese. The missionaries had stayed on in Panay on their own will, and had been going on with the green chapel activities in a place called Hopevale in the jungle. Her elder siblings of course knew the atrocious incident. She generously met us, snatching time from a meeting.

Prof. Meloy is a smart, warm-hearted lady, and is full of humor. In her busy schedule of teaching and administration duties, she found time for editing, and during the last few weeks of the project, she organized a list-serve connecting three points: herself, Prof. Rico at Manila, and Mr. Kumai/me in Tokyo, through which we, the two professors took trouble of proof reading, involving us. Then Professor Meloy visited the printer more than once to see the work done. She also contacted all the people in Kumai’s guest list, who he wanted to invite to the ceremonies and Buffet Dinner on March 28. After Kumai’s arrival, she supported the film making featuring Mr. Kumai at the old war spots, arranging the university vehicle, and attending herself. Meloy and Dawn: they are both gifted with abilities and love. One is a business woman, another is a professor; both ladies of a large caliber. I can imagine wonderful female advancement in Filipino society.

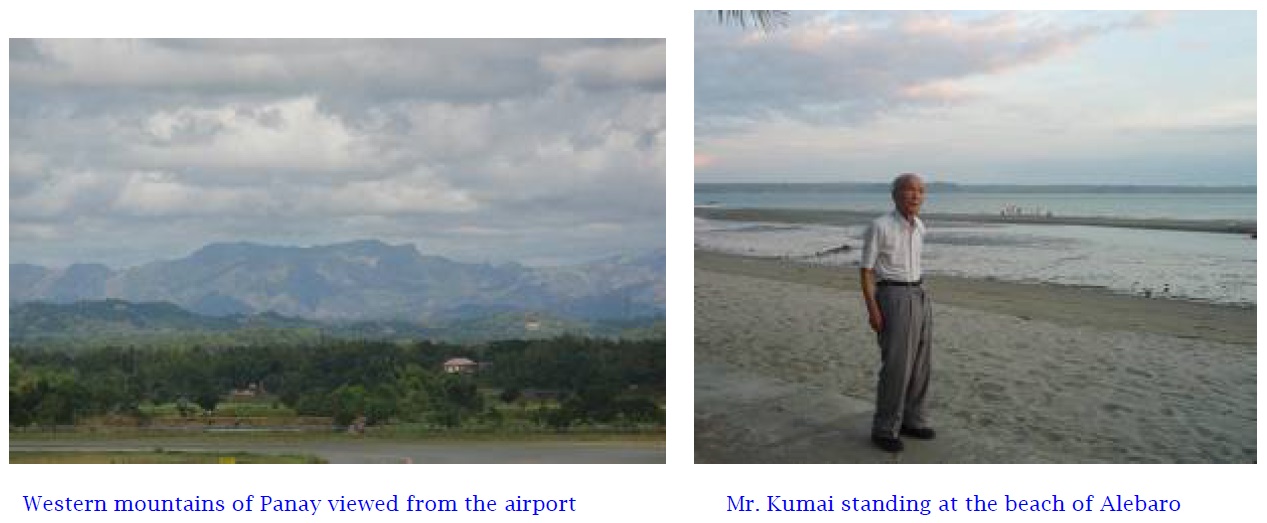

March 31: Leaving Panay

From left: Chizuko, Stephanie, a volunteer for Nikkeijin-kai,

Geordinie, guard of the Amigo Hotel, whose grandfather was a

guerrilla in Capiz, so he had Mr. Kumai sign in his book, me, and

Dawn. Ms Mila O. Yotoko, on the extreme right, is another

volunteer for Nikkeijin-kai, and proud mother of capable and

lovely Stephanie. Mila’s sister Jessie is Principal of the

kindergarten of the Nikkeijin-kaikan. With her brother Mr Eric Yotoko, all the family, besides

pursuing their own businesses, cooperated with the dedicated staff of the Nikkeijin-kai, made a

great effort, and led all the visits and ceremonies to a great success, including the fantastic

home made dishes at the memorial dinner. Caring for and reaching out to Mr. Kumai,

protecting him from the sun with an umbrella: had it not been for the devoted assistance of the

three, and Filipino friends at Nikkeijinkai, we could never have been able to have such

wonderful times. Last but not least, I with all the Japanese attendants, give our big and heartfelt

“Thank you” to them.

From left: Chizuko, Stephanie, a volunteer for Nikkeijin-kai,

Geordinie, guard of the Amigo Hotel, whose grandfather was a

guerrilla in Capiz, so he had Mr. Kumai sign in his book, me, and

Dawn. Ms Mila O. Yotoko, on the extreme right, is another

volunteer for Nikkeijin-kai, and proud mother of capable and

lovely Stephanie. Mila’s sister Jessie is Principal of the

kindergarten of the Nikkeijin-kaikan. With her brother Mr Eric Yotoko, all the family, besides

pursuing their own businesses, cooperated with the dedicated staff of the Nikkeijin-kai, made a

great effort, and led all the visits and ceremonies to a great success, including the fantastic

home made dishes at the memorial dinner. Caring for and reaching out to Mr. Kumai,

protecting him from the sun with an umbrella: had it not been for the devoted assistance of the

three, and Filipino friends at Nikkeijinkai, we could never have been able to have such

wonderful times. Last but not least, I with all the Japanese attendants, give our big and heartfelt

“Thank you” to them.

Article by: Yuka Ibuki